Dr David Hegarty

The Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS-10) is a 10-item self-report measure designed to assess emotional intelligence (EI) in adults. The BEIS-10 was developed by Davies et al. (2010) as a shortened version of the 33-item Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS; Schutte et al., 1998).

- 2 minutes

- Ages 18+

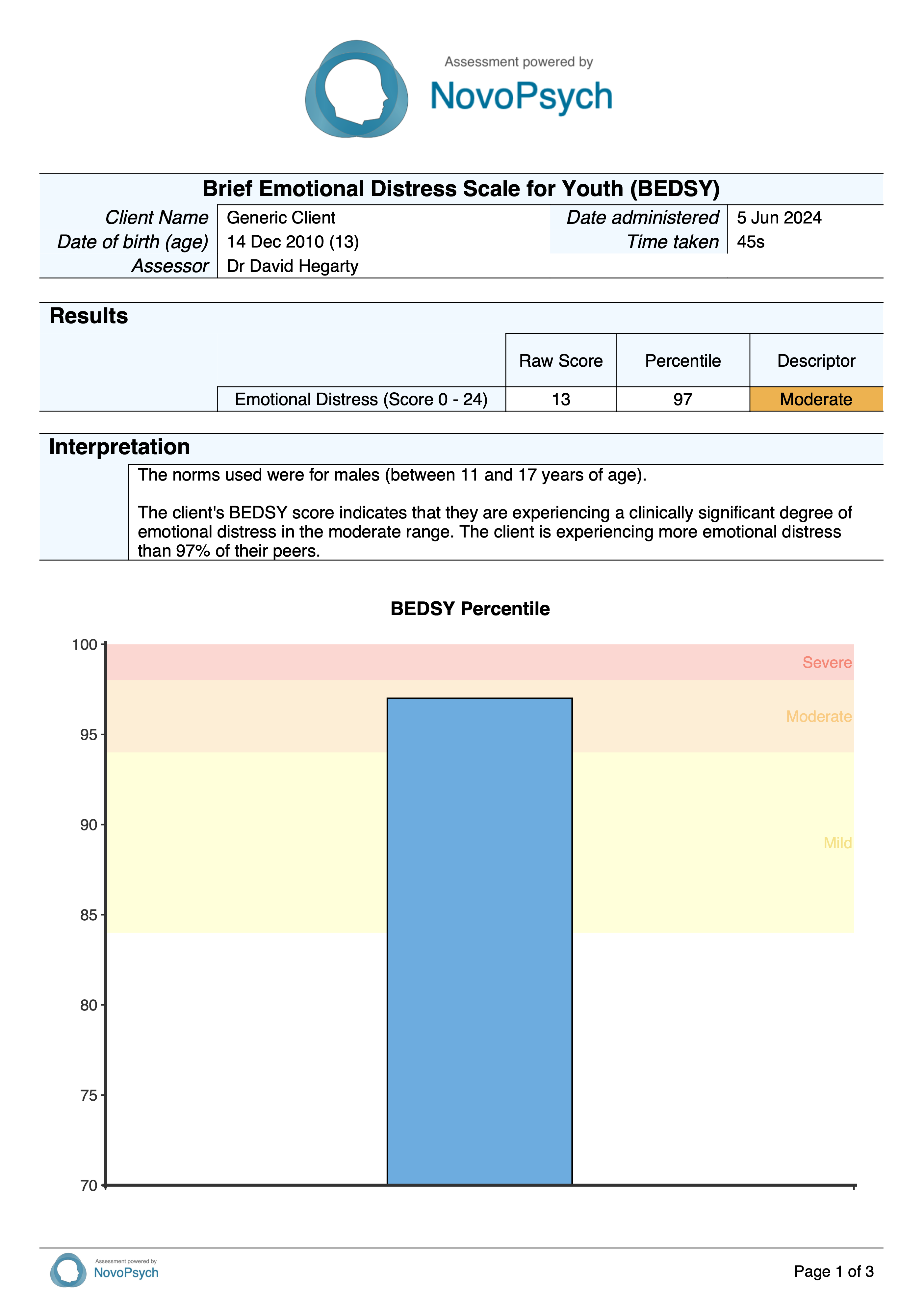

- Formulation

The BEIS-10 is based on Salovey and Mayer’s (1990) theoretical framework which posits that emotionally intelligent individuals can accurately perceive emotions (both in themselves and others), use emotions to facilitate thinking and problem solving, understand the meaning of emotions, and manage emotions effectively. EI develops over time and represents a distinct type of intelligence that contributes to more adaptive psychological functioning.

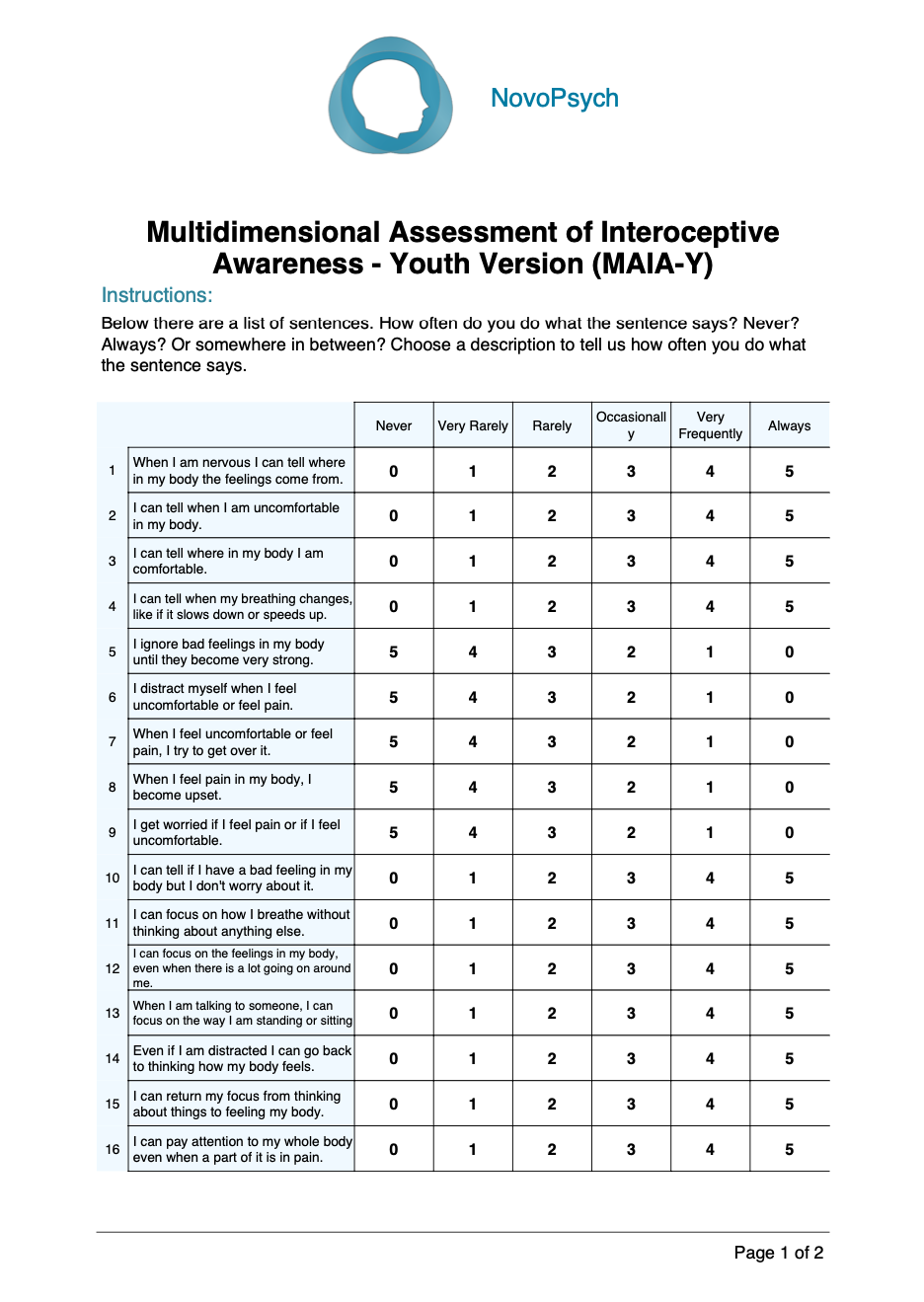

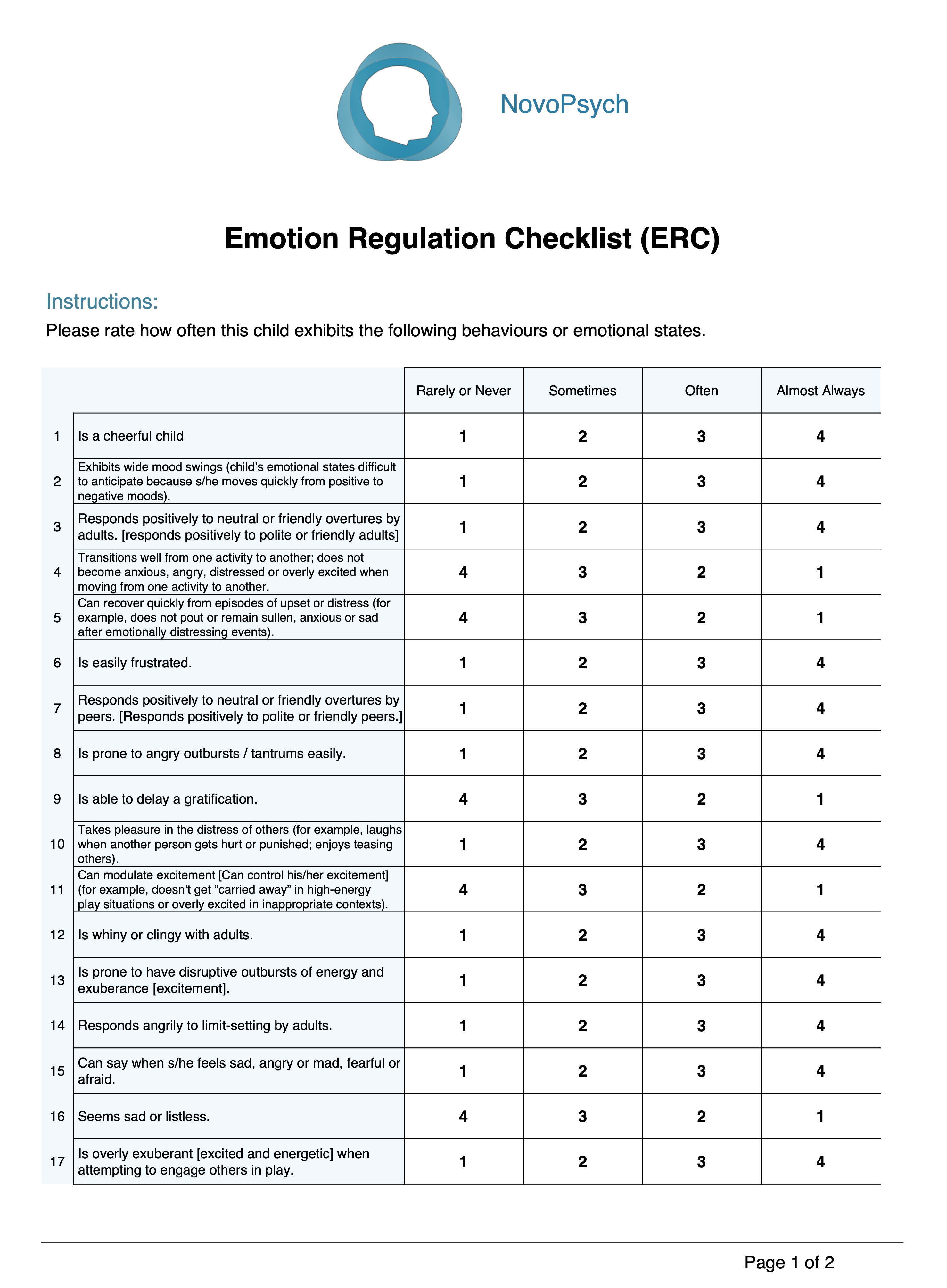

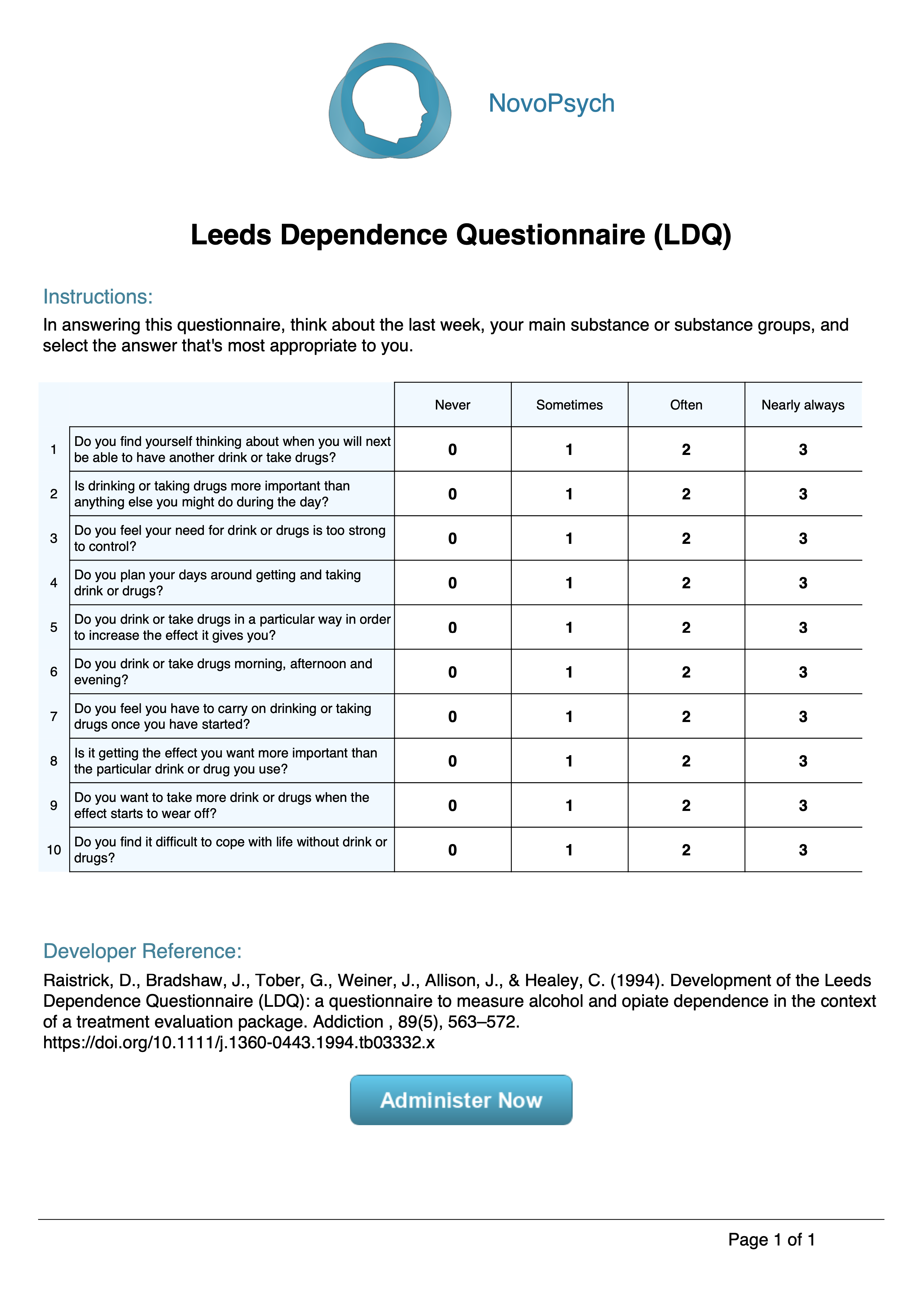

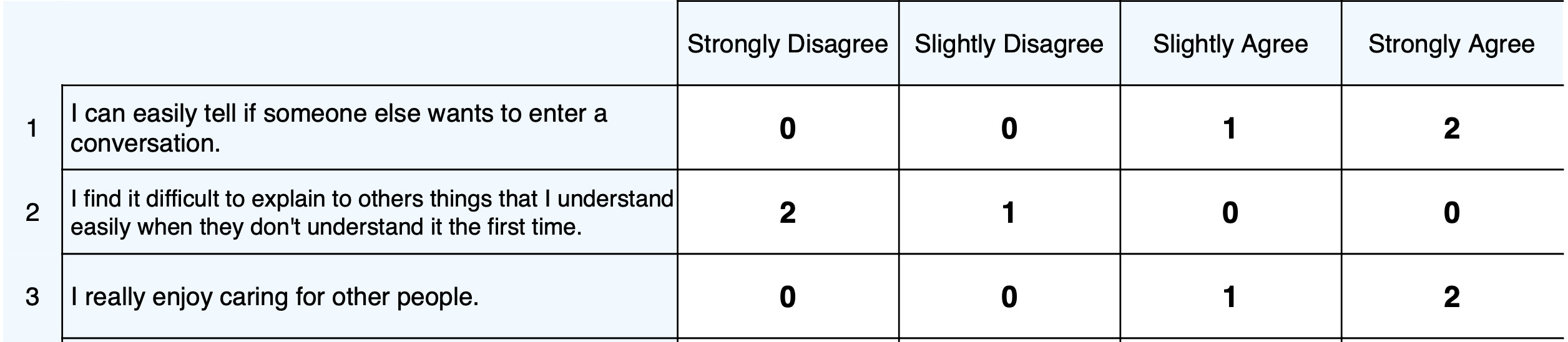

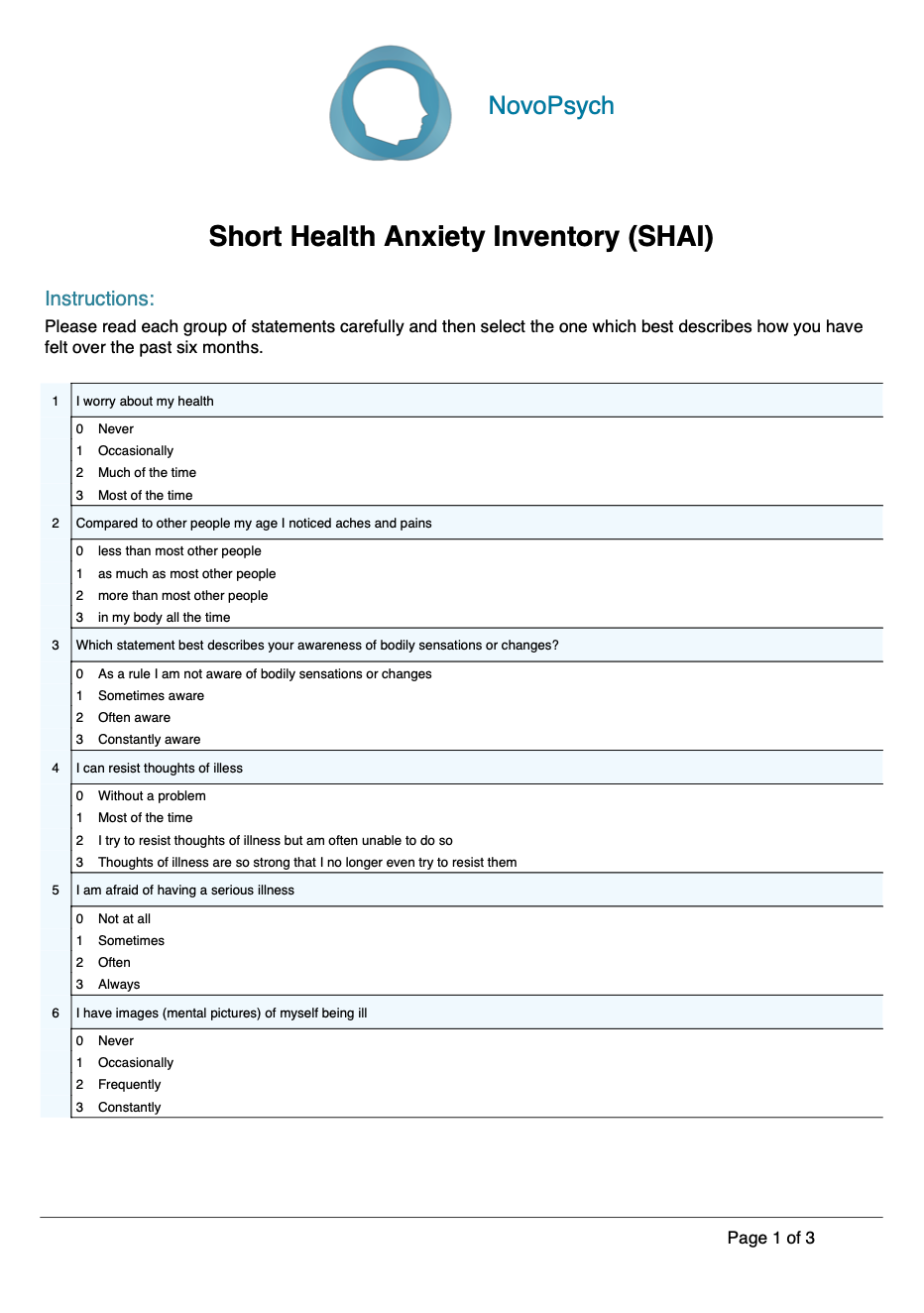

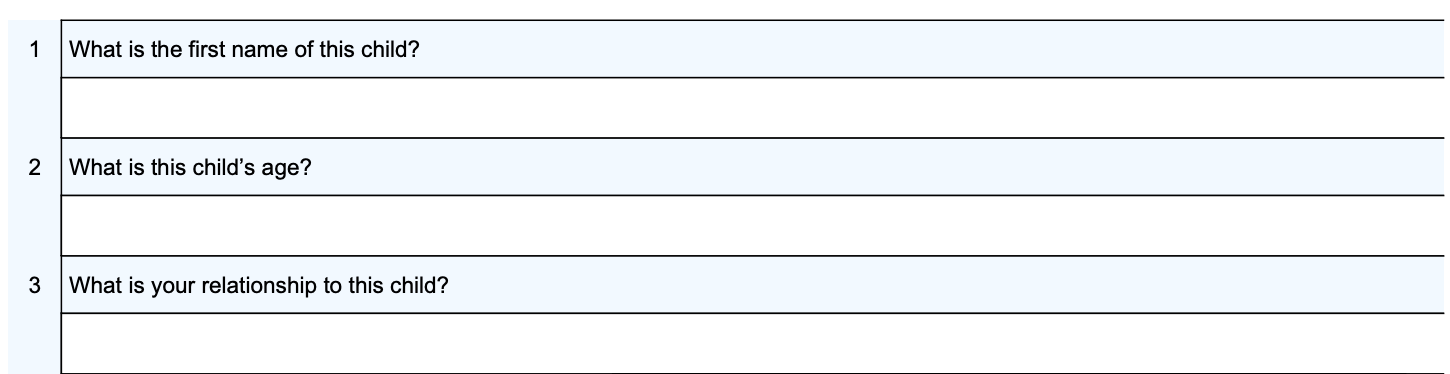

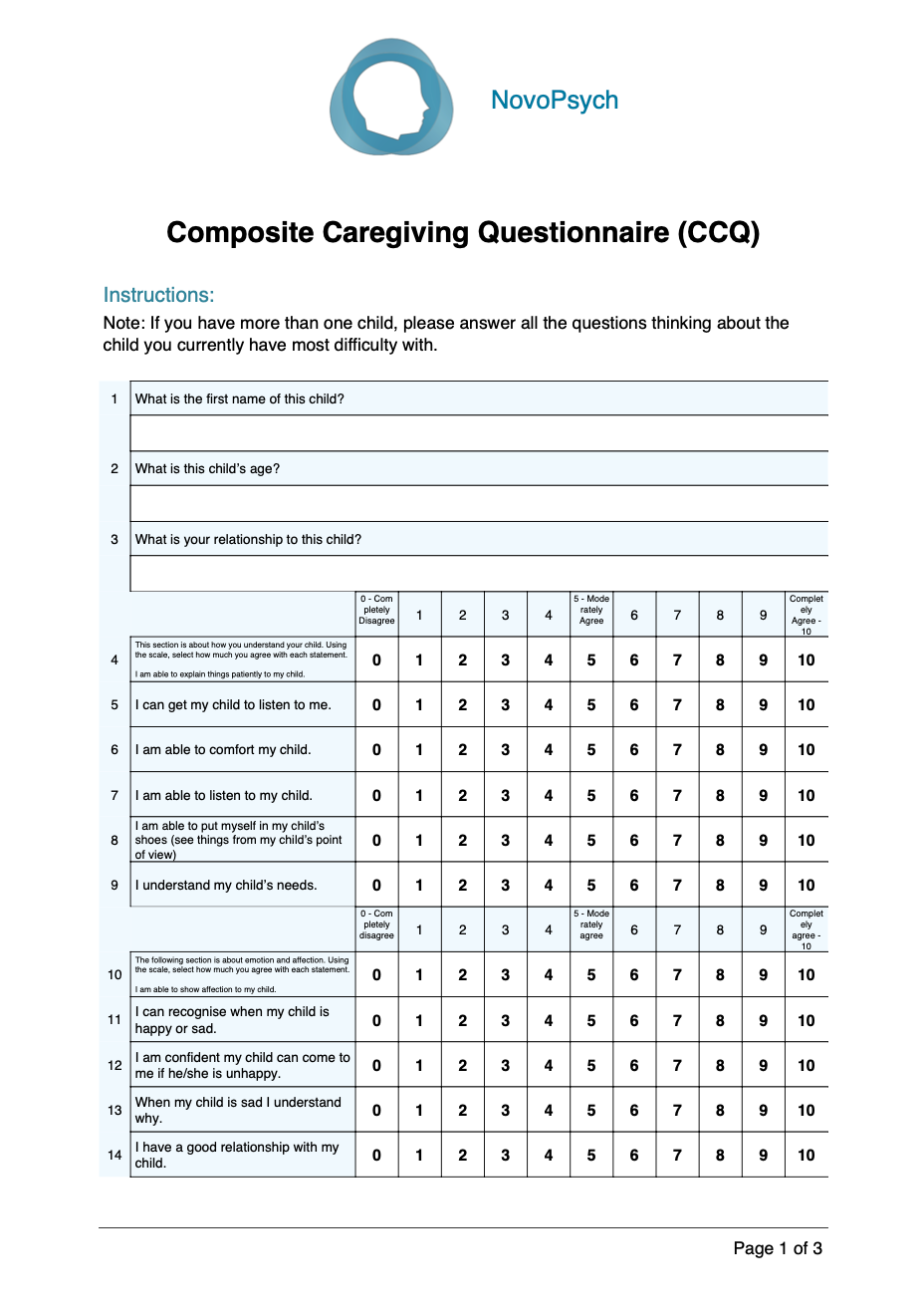

The BEIS-10 measures five distinct EI dimensions:

- Appraisal of Own Emotions – assessing an individual’s ability to recognise and identify their own emotional states

- Appraisal of Others’ Emotions – measuring the capacity to interpret and understand emotions in others through verbal and nonverbal cues

- Regulation of Own Emotions – evaluating an individual’s perceived ability to control and manage their emotional responses

- Regulation of Others’ Emotions – assessing perceived ability to influence and manage the emotional states of others

- Utilisation of Emotions – measuring how effectively individuals can use emotional states to facilitate problem-solving and creativity

For clinicians, assessing EI can provide valuable insights into client outcomes across multiple domains. Meta-analytic studies have demonstrated the predictive utility of EI across both health-related outcomes (including physical and mental health; Schutte et al., 2007) and performance-related variables (such as academic achievement and occupational performance; Van Rooy & Viswesvaran, 2004). This evidence suggests that understanding a client’s EI profile can help inform interventions targeting both wellbeing and performance enhancement.

The BEIS-10’s development addresses a significant need in clinical practice for a brief, theoretically-sound measure of EI that can inform case conceptualisation, treatment planning and approach to building the therapeutic relationship. Its structure permits examination of both overall EI and specific EI components, enabling clinicians to develop more targeted and effective interventions based on their clients’ specific emotional processing strengths and challenges. The BEIS-10 highlights both areas of challenge that may become specific treatment targets as well as areas of strength considered protective or to be leveraged to support the therapeutic process.

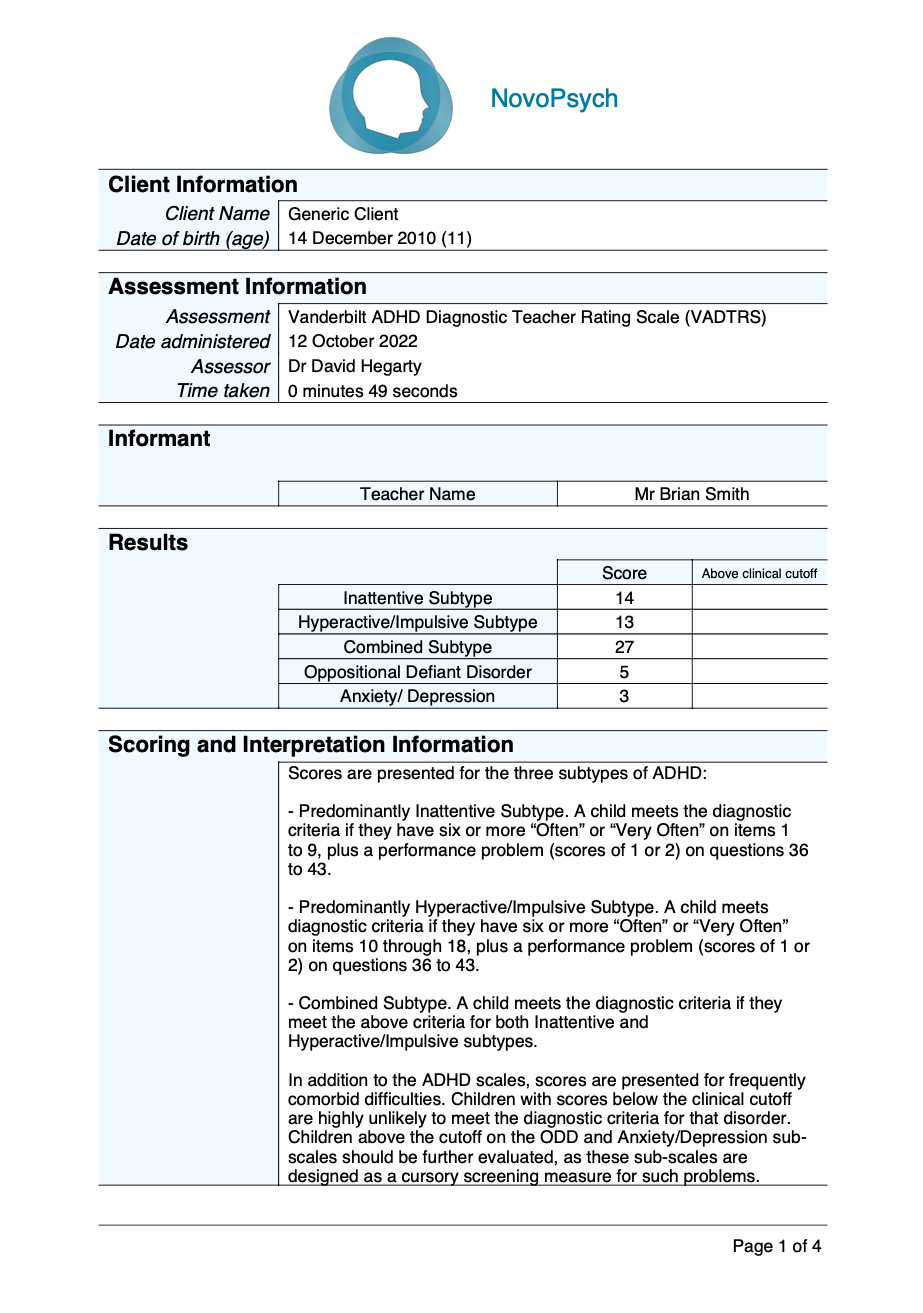

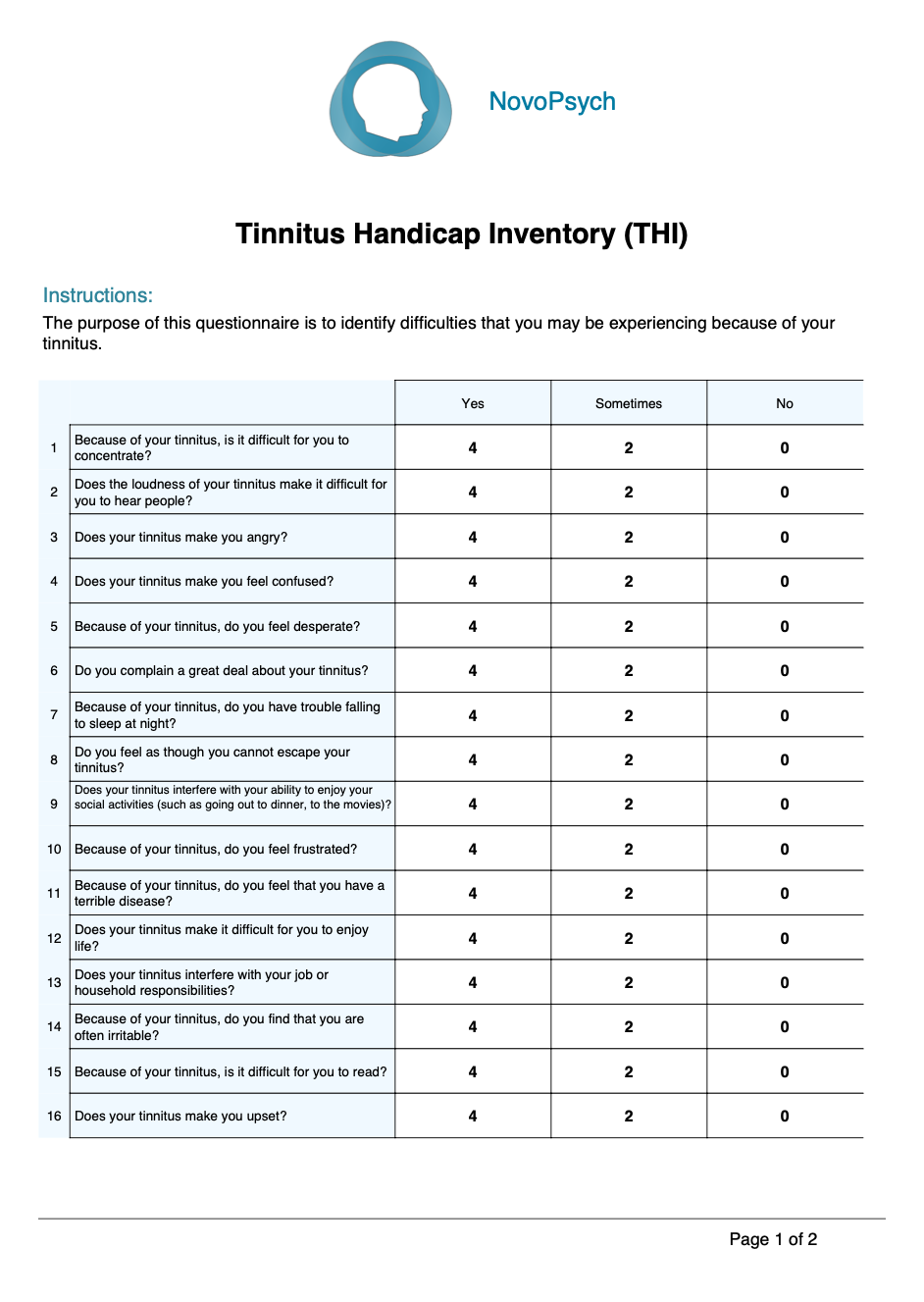

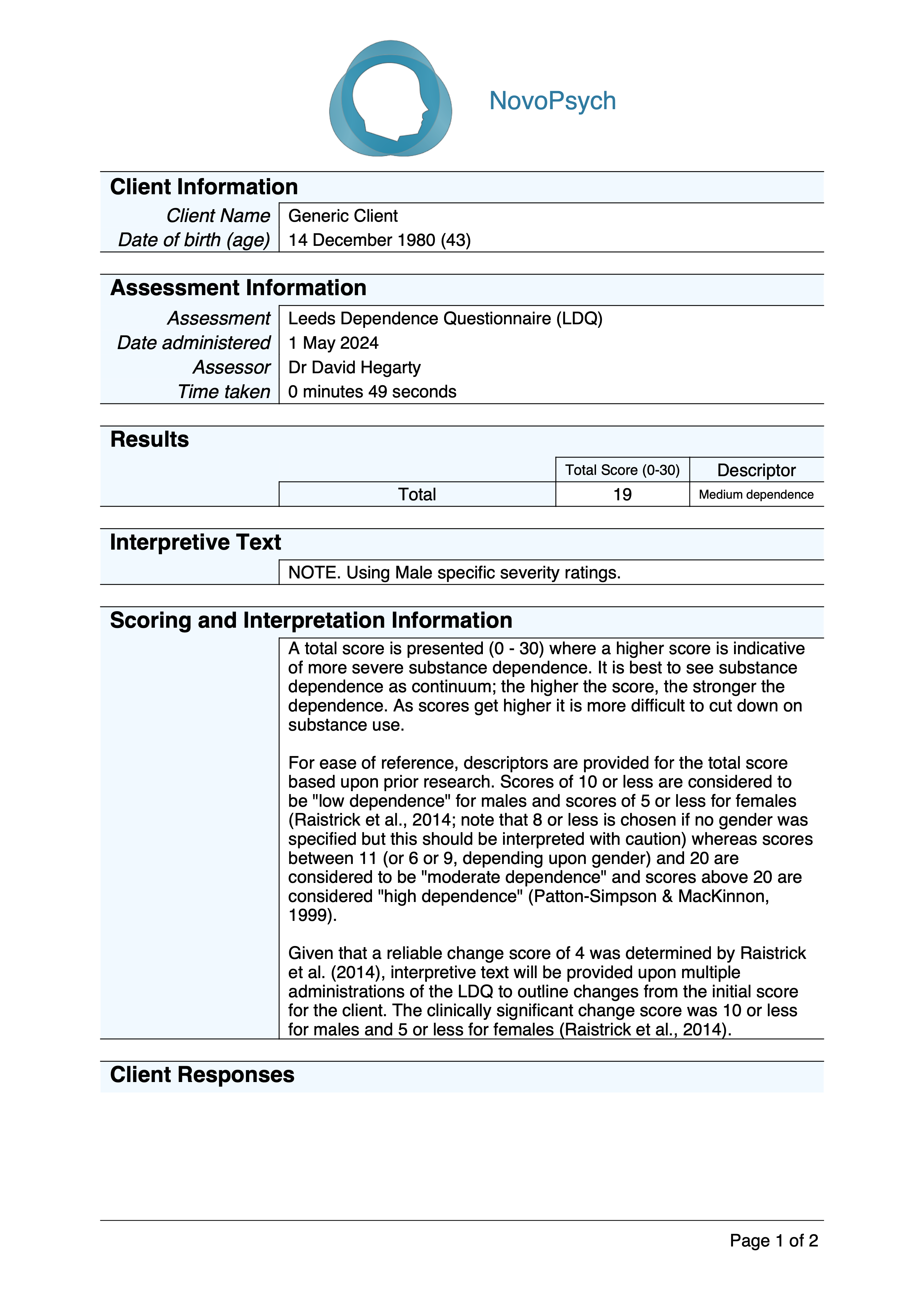

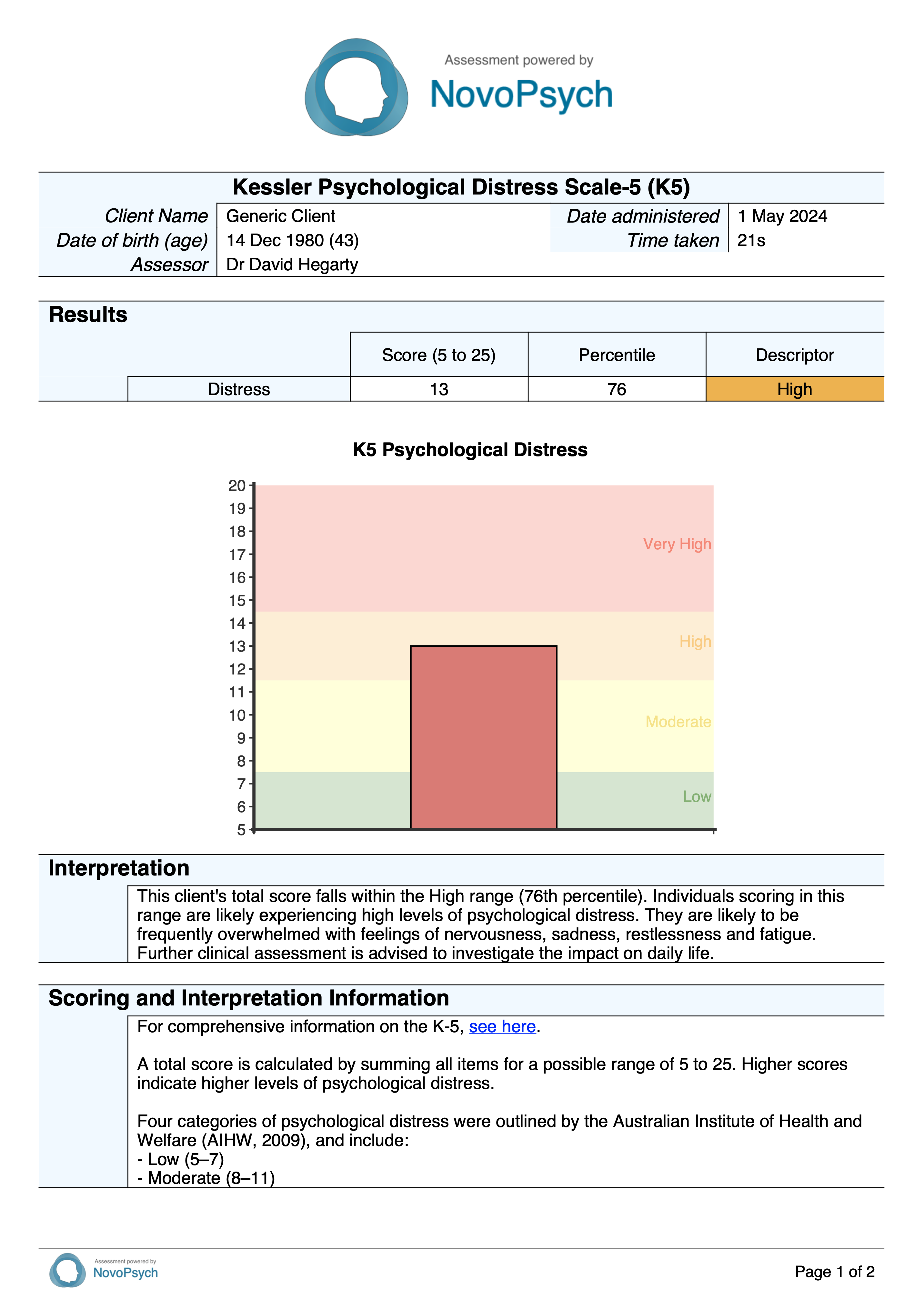

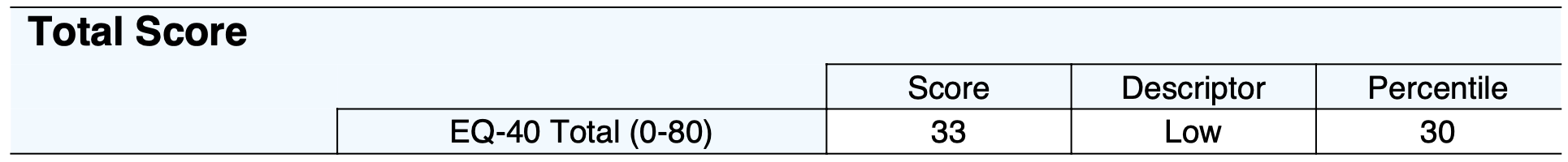

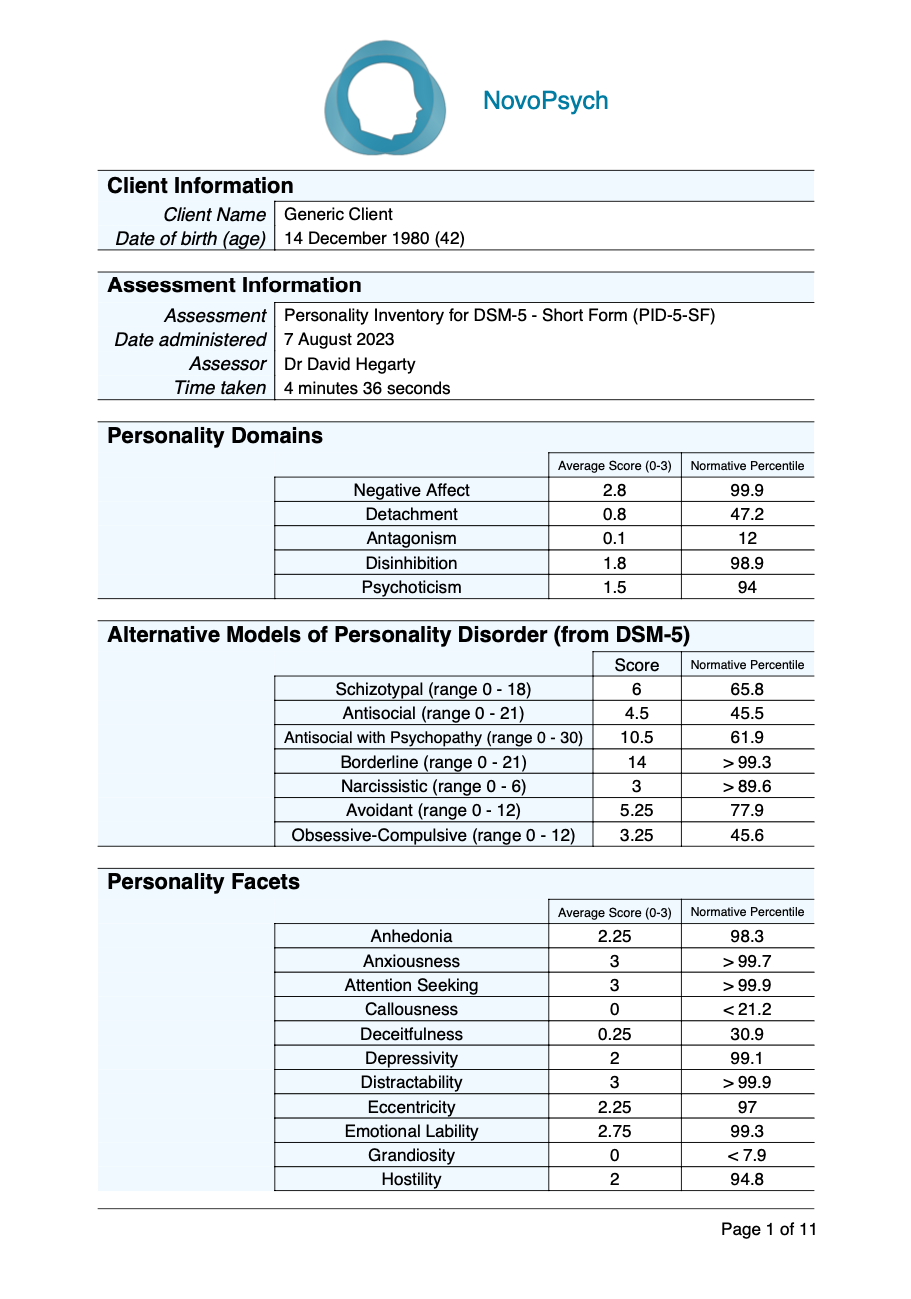

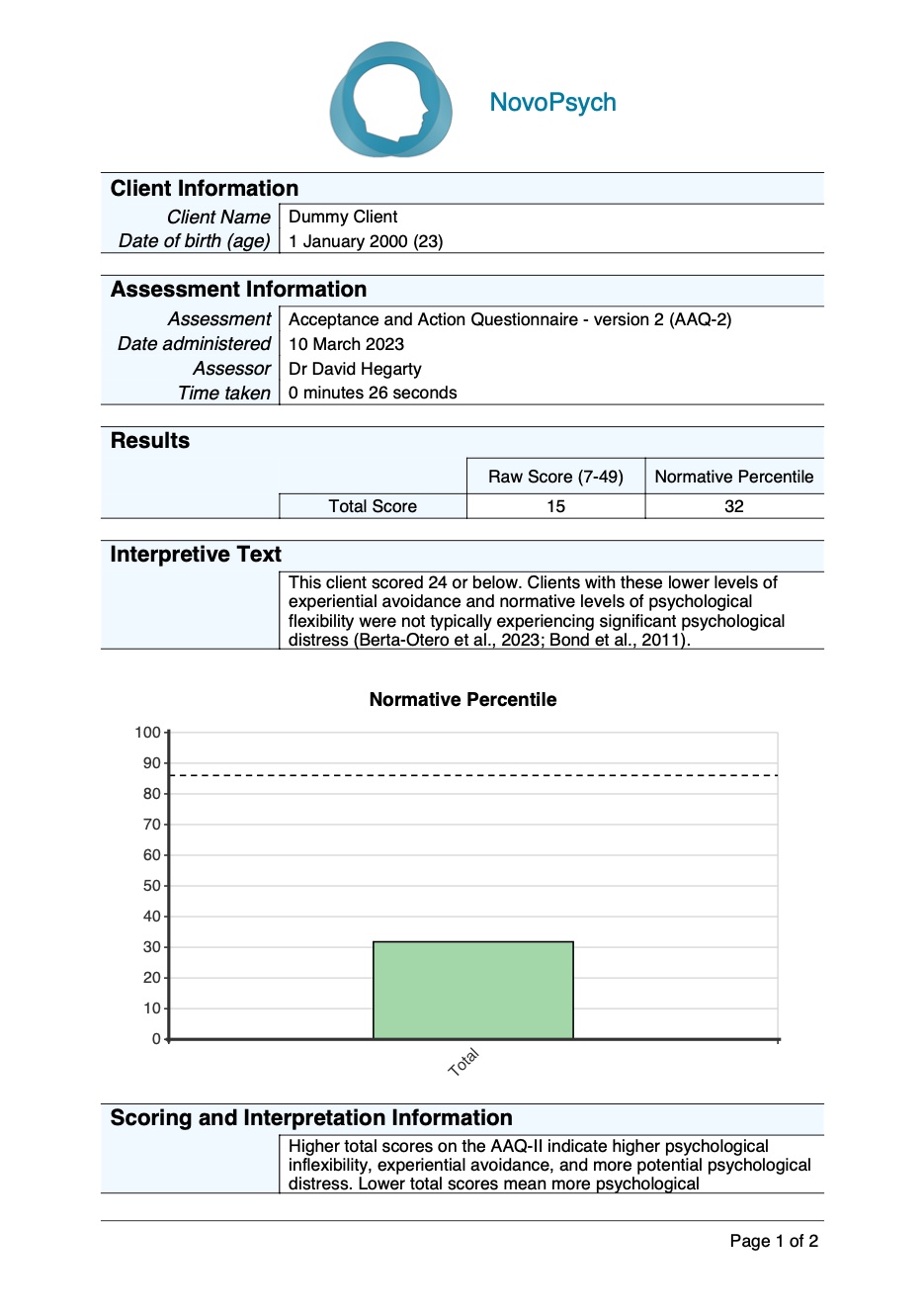

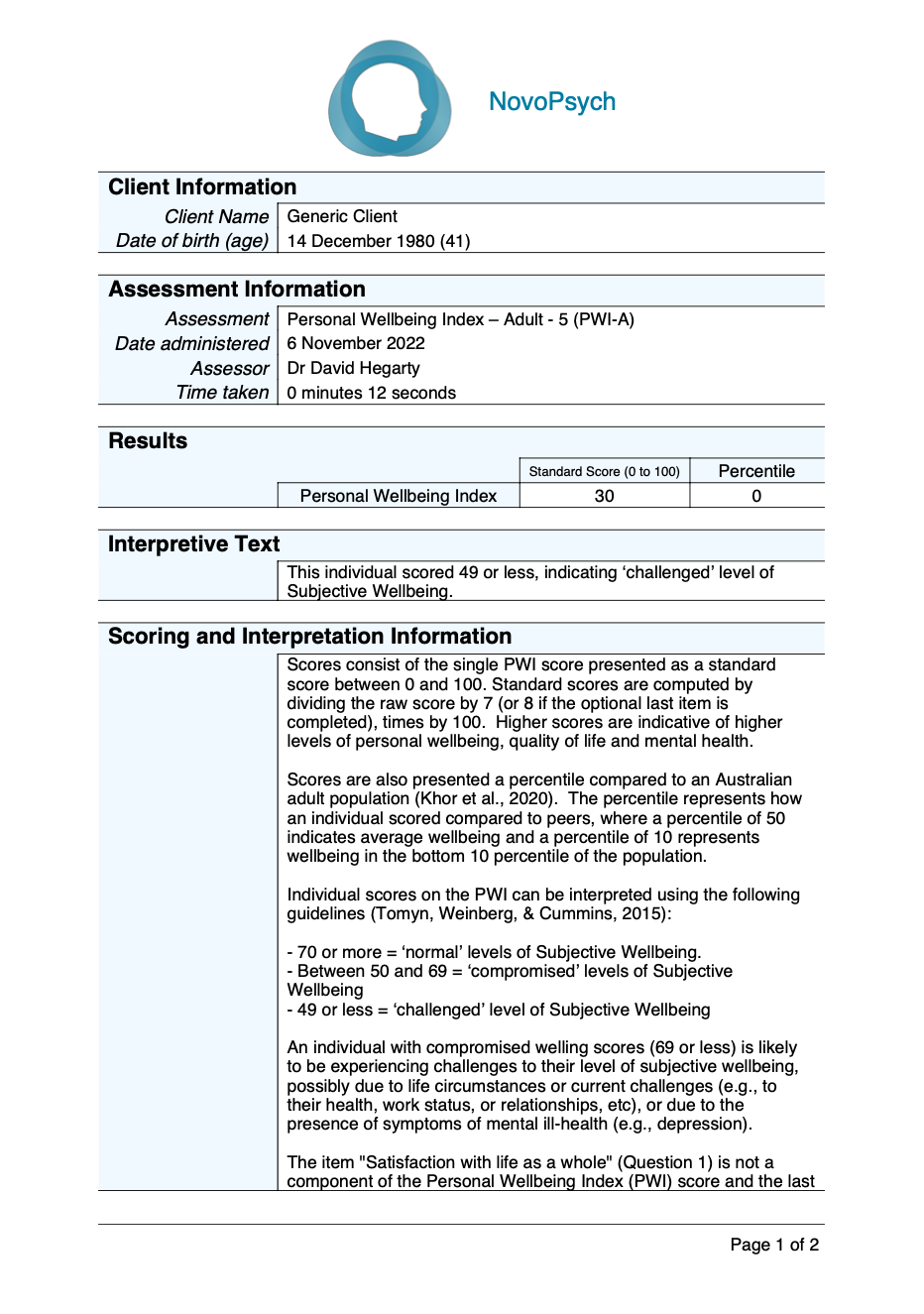

BEIS-10 scores consist of a total raw score (range from 10 to 50) and five sub-scale scores, with higher scores indicating greater self-perceived emotional intelligence capabilities. These scores are converted into percentiles based on a large combined normative sample (N = 2,770) drawn from multiple studies across different populations and countries.

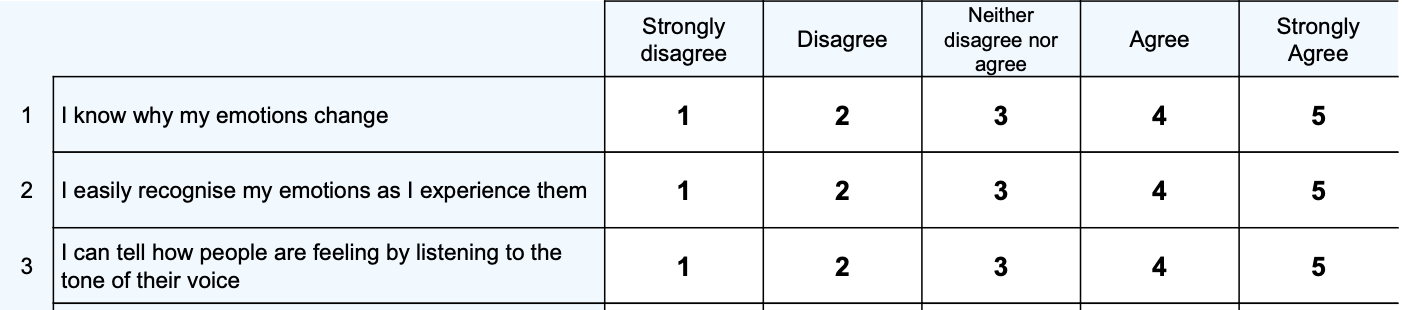

Sub-scales are presented for the BEIS-10:

- Appraisal of Own Emotions (items 1, 2; range 2-10): Assesses an individual’s capacity to identify and understand their own emotional states. This includes awareness of mood changes, recognition of physiological responses to emotions, and the ability to label emotional experiences accurately.

- Appraisal of Others’ Emotions (items 3, 4; range 2-10): Measures one’s ability to accurately perceive and interpret others’ emotional states through both verbal and non-verbal cues. This includes recognition of facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language.

- Regulation of Own Emotions (items 5, 6; range 2-10): Evaluates an individual’s ability to manage and modify their emotional responses. This includes skills in emotional self-control, ability to calm oneself when upset, and capacity to maintain emotional balance.

- Regulation of Others’ Emotions (items 7, 8; range 2-10): Assesses capability to influence and manage others’ emotional states. This includes helping others feel better when down, providing emotional support, and facilitating positive emotional states in others.

- Utilisation of Emotions (items 9, 10; range 2-10): Measures how effectively individuals harness emotions to enhance thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. This includes using emotions to guide decision-making and leveraging emotional states for improved performance.

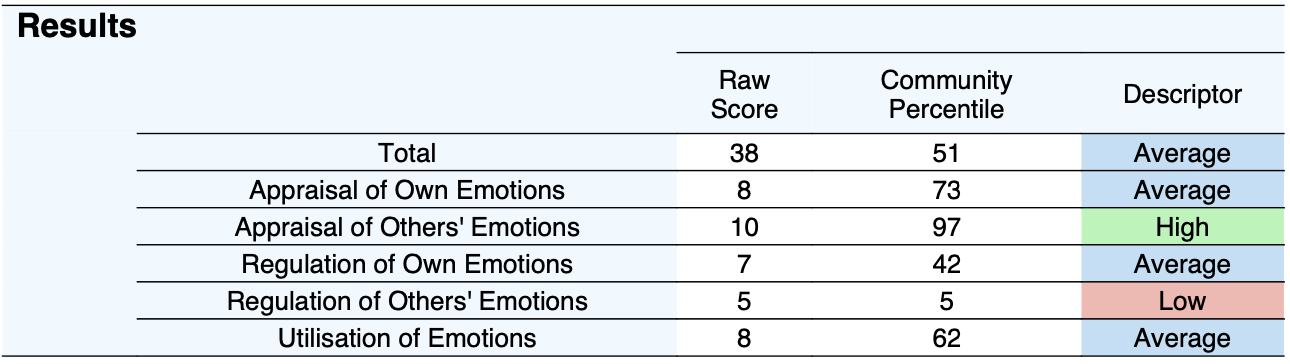

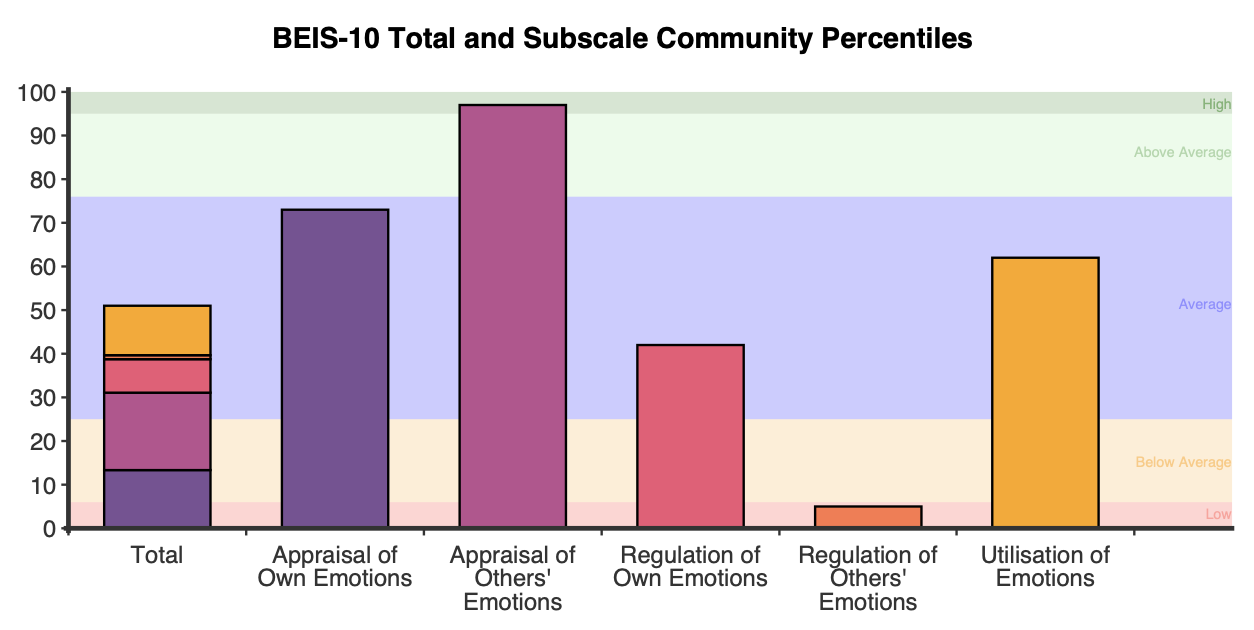

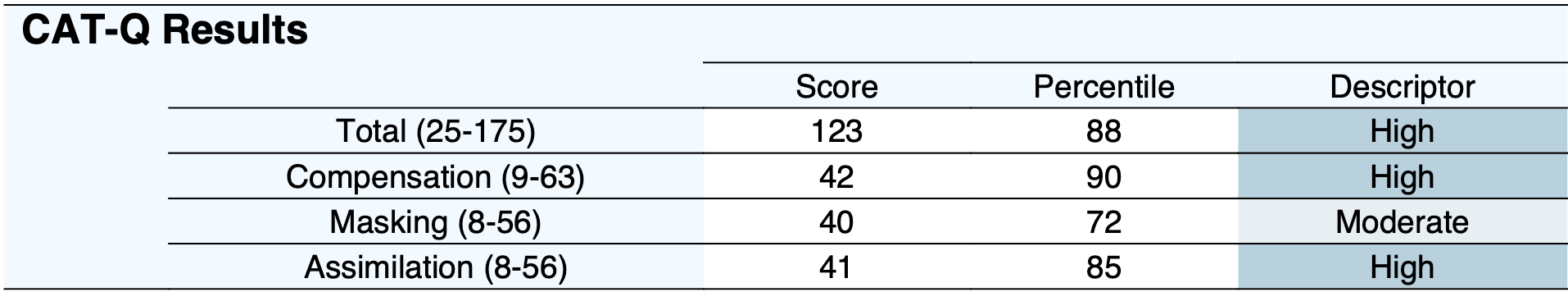

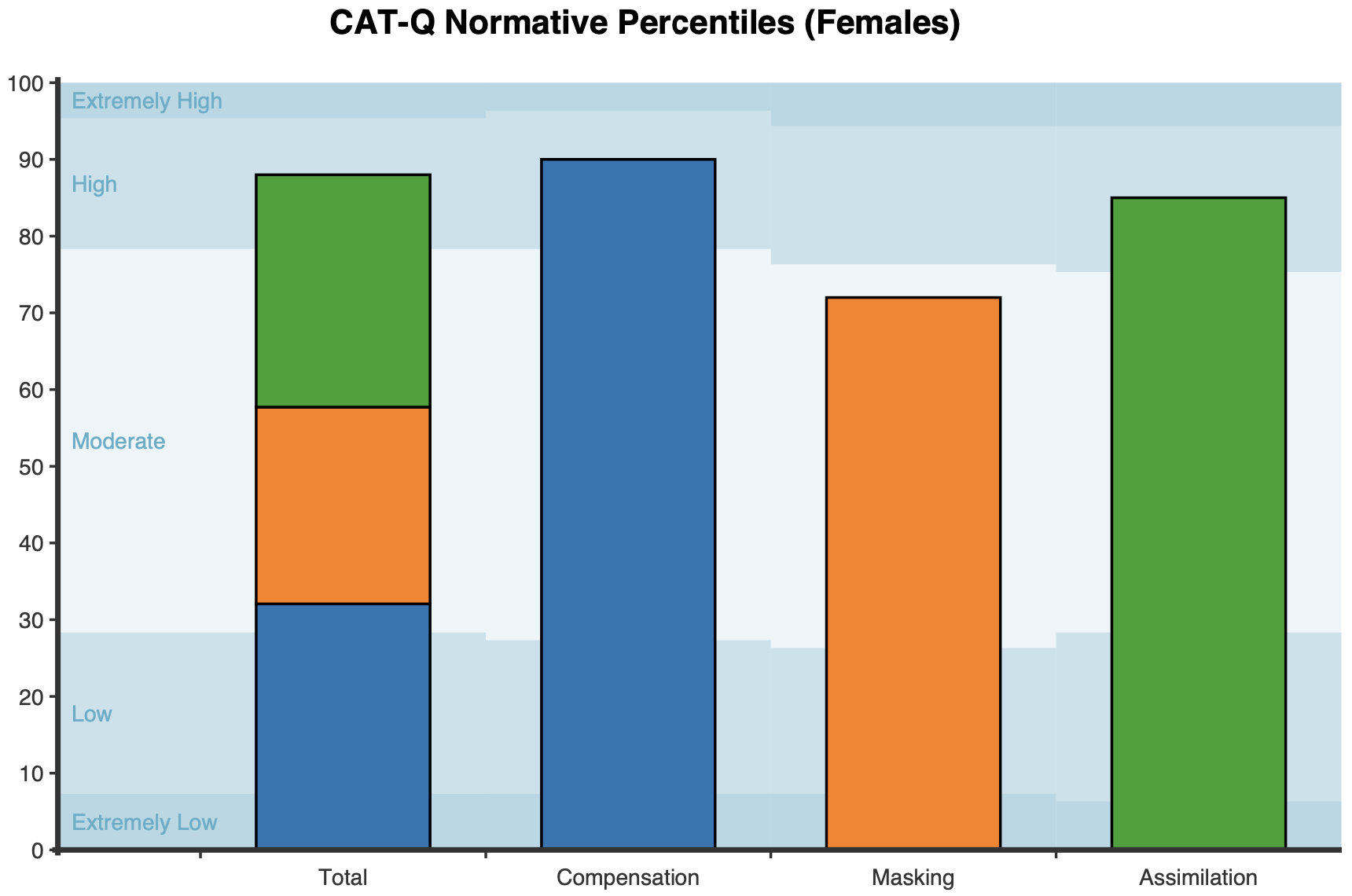

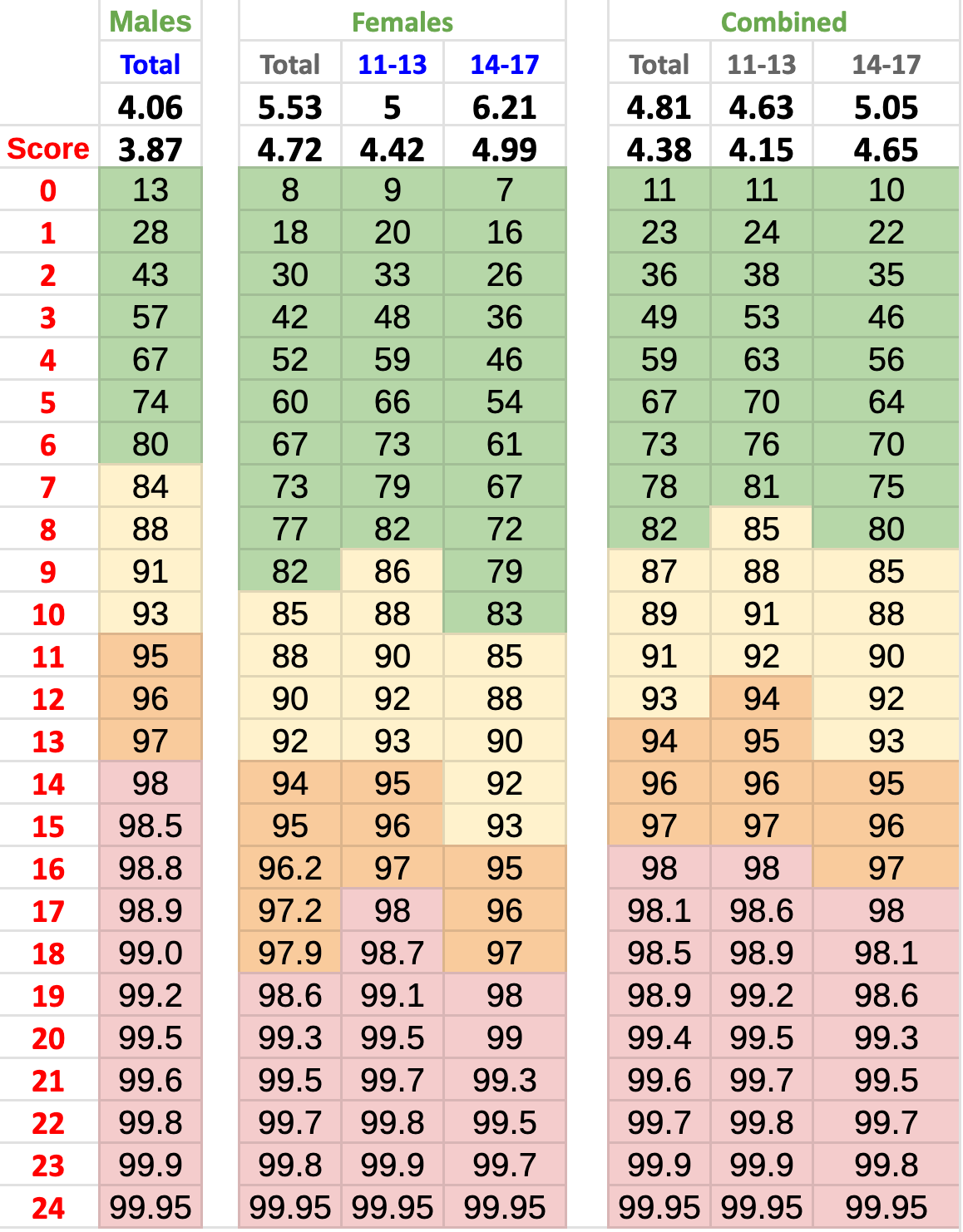

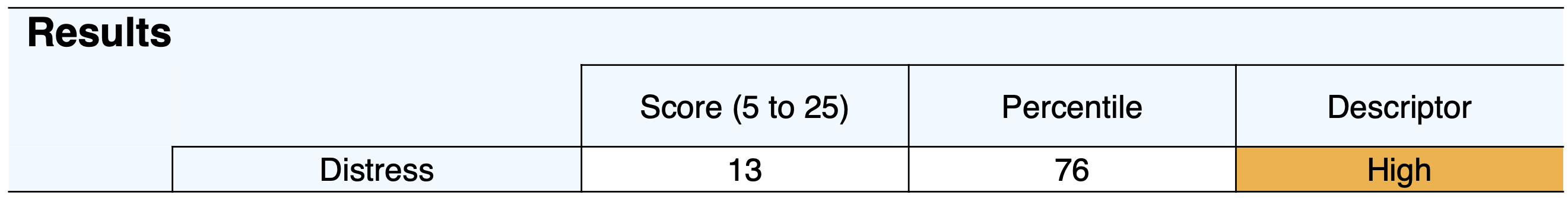

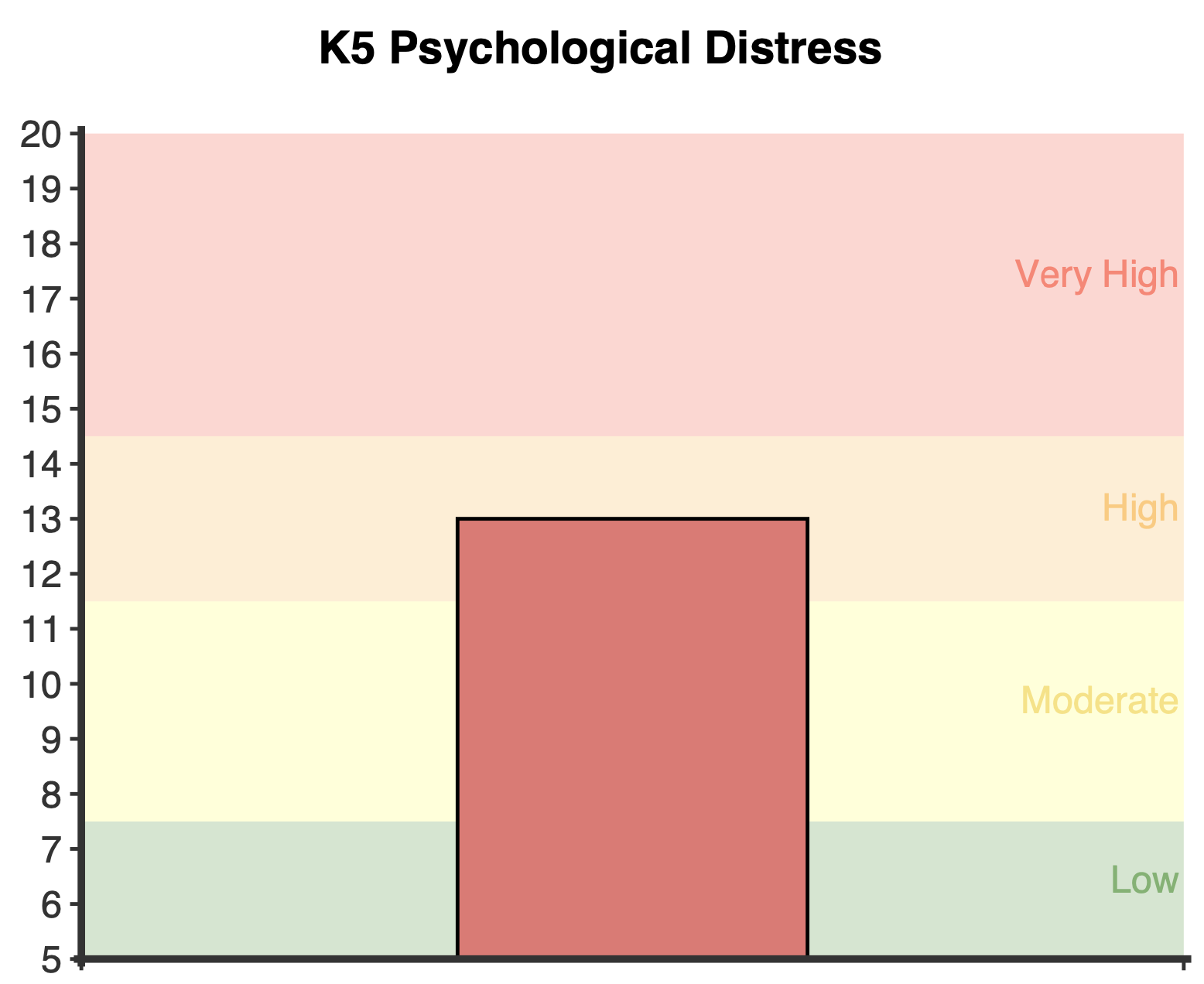

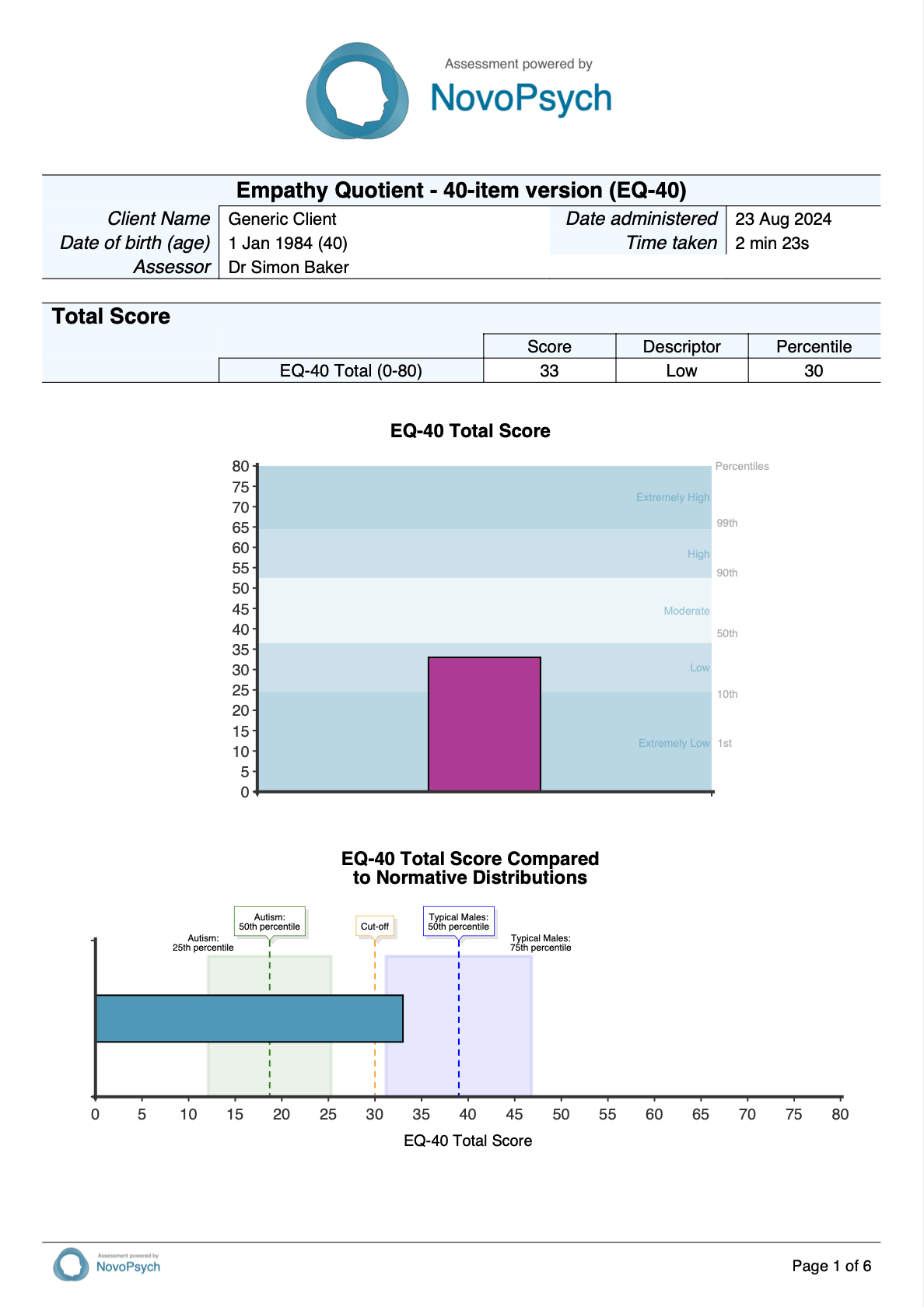

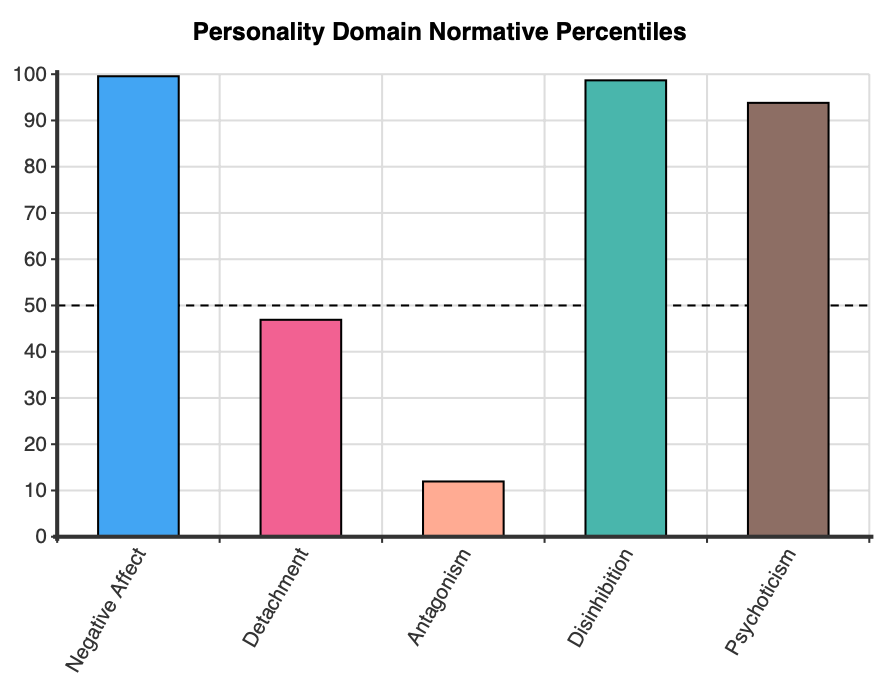

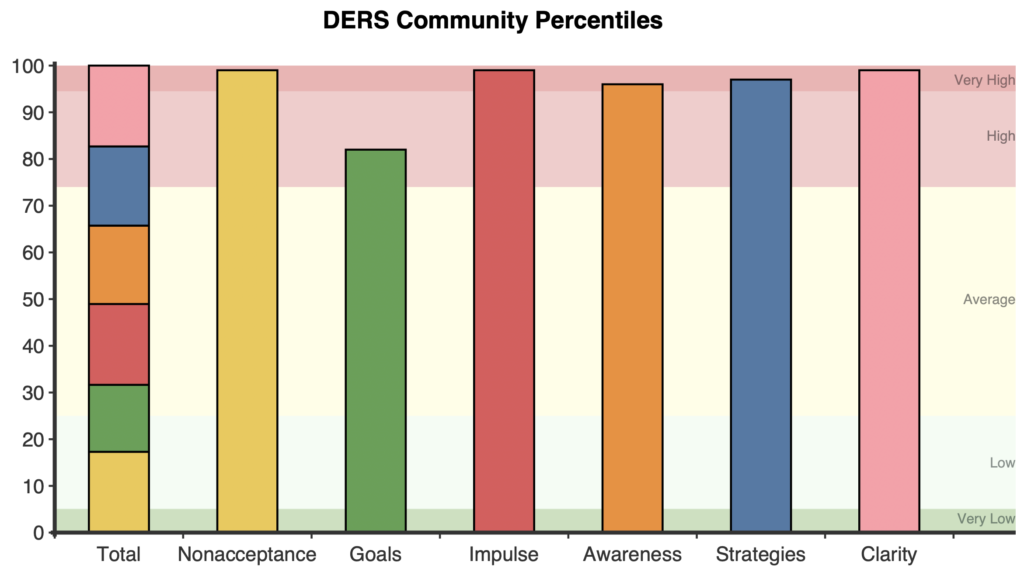

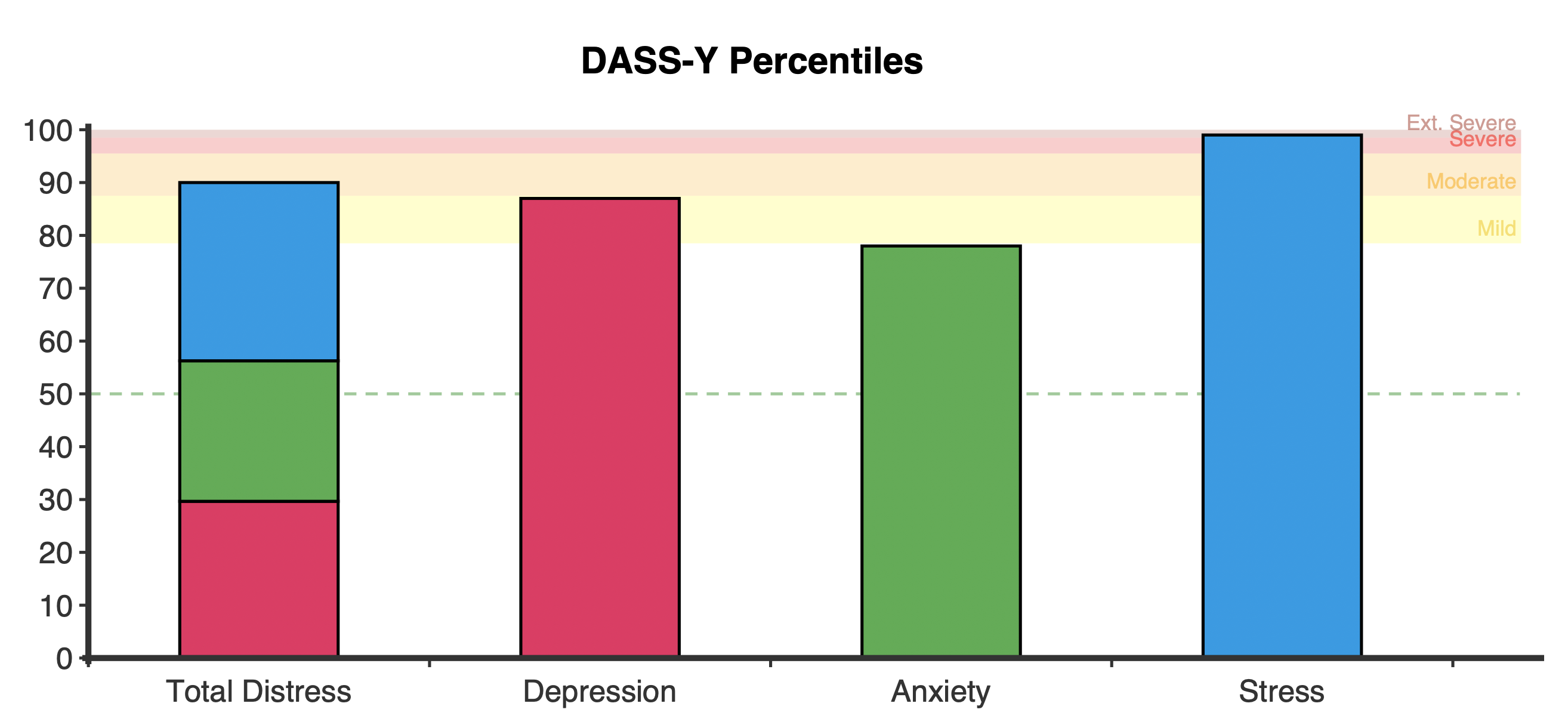

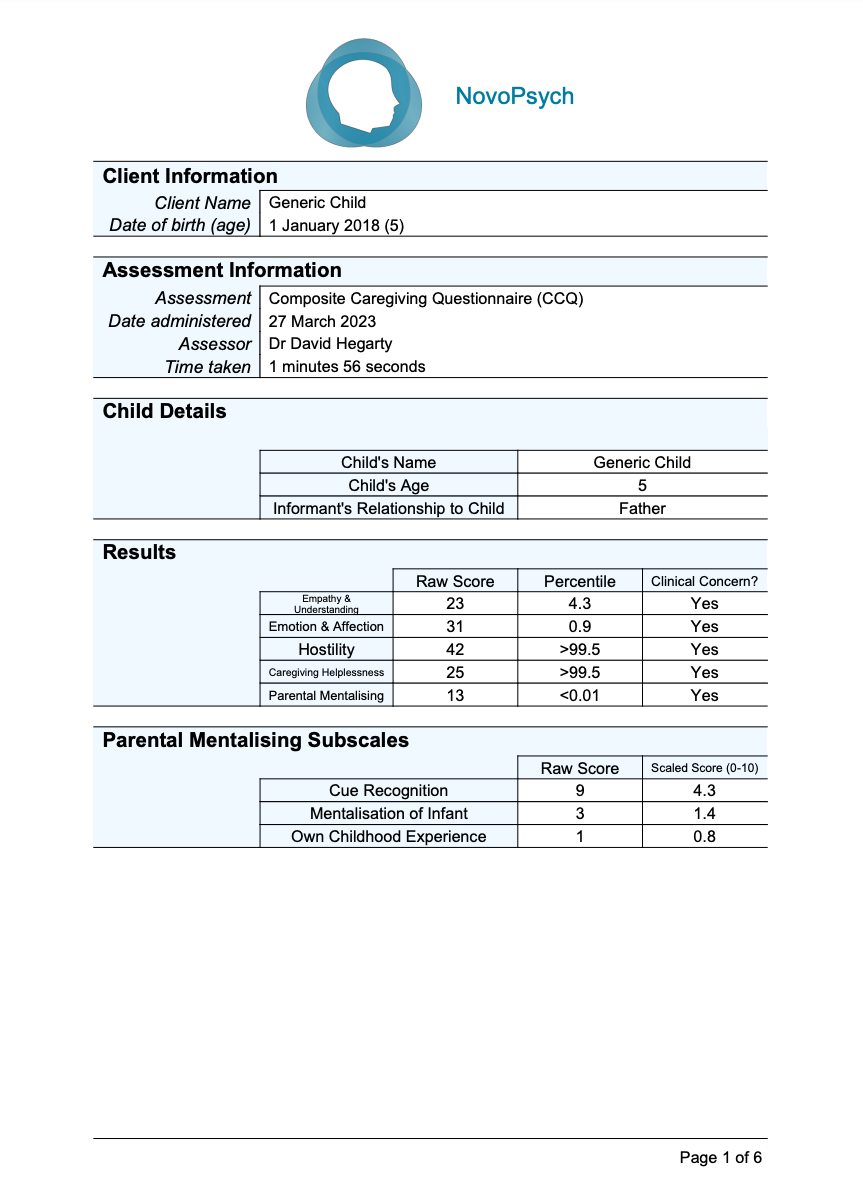

A percentile score interpretation framework provides qualitative descriptors ranging from Low to High emotional intelligence:

- Low: 5th percentile and below

- Below Average: 6th to 24th percentile

- Average: 25th to 75th percentile

- Above Average: 76th to 94th percentile

- High: 95th percentile and above

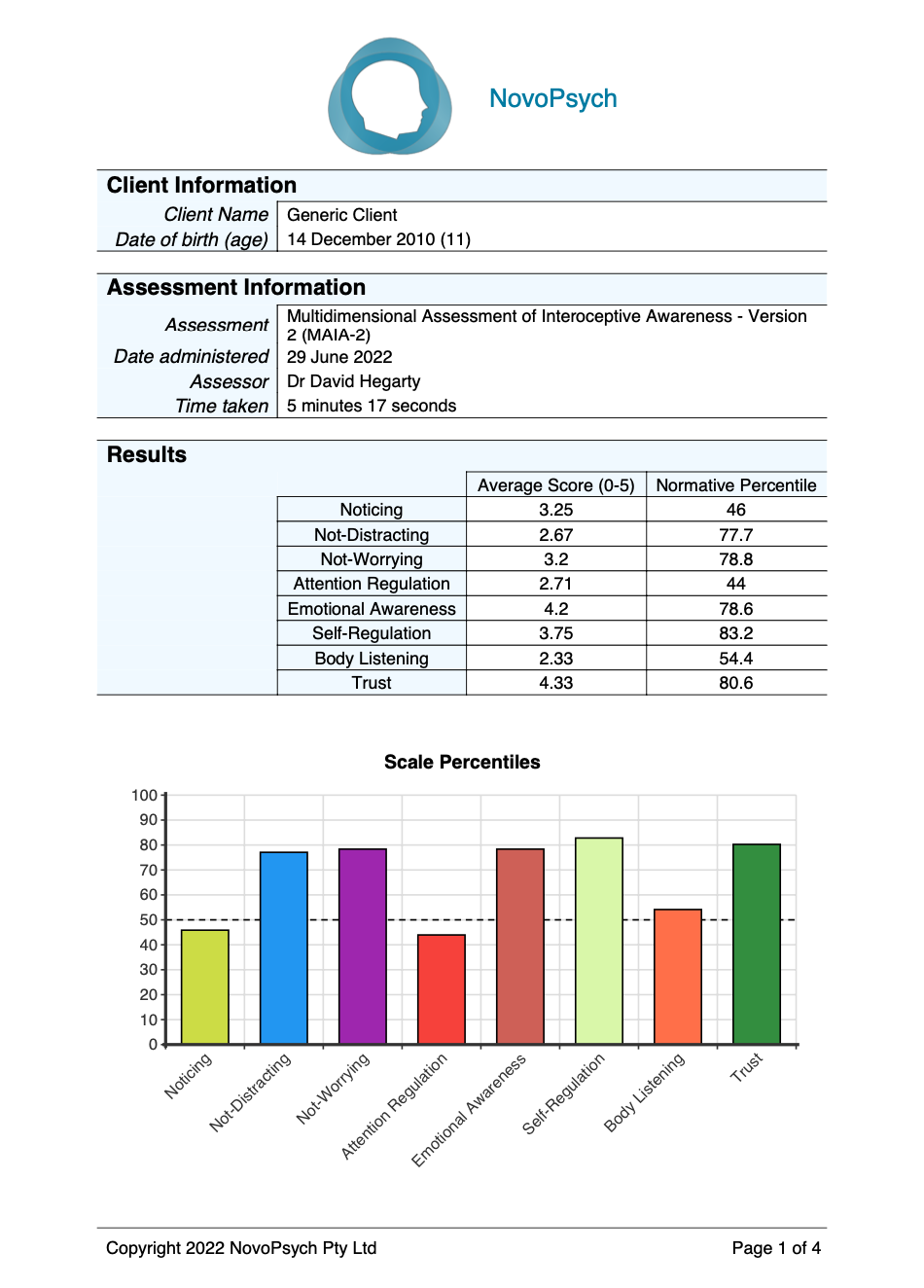

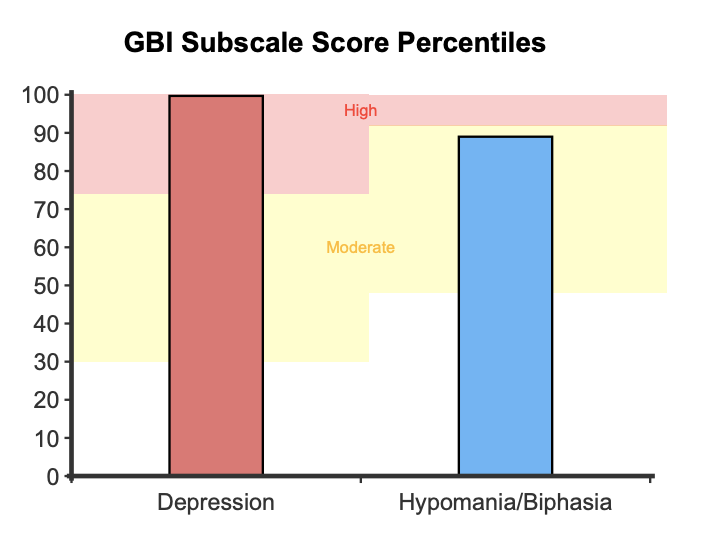

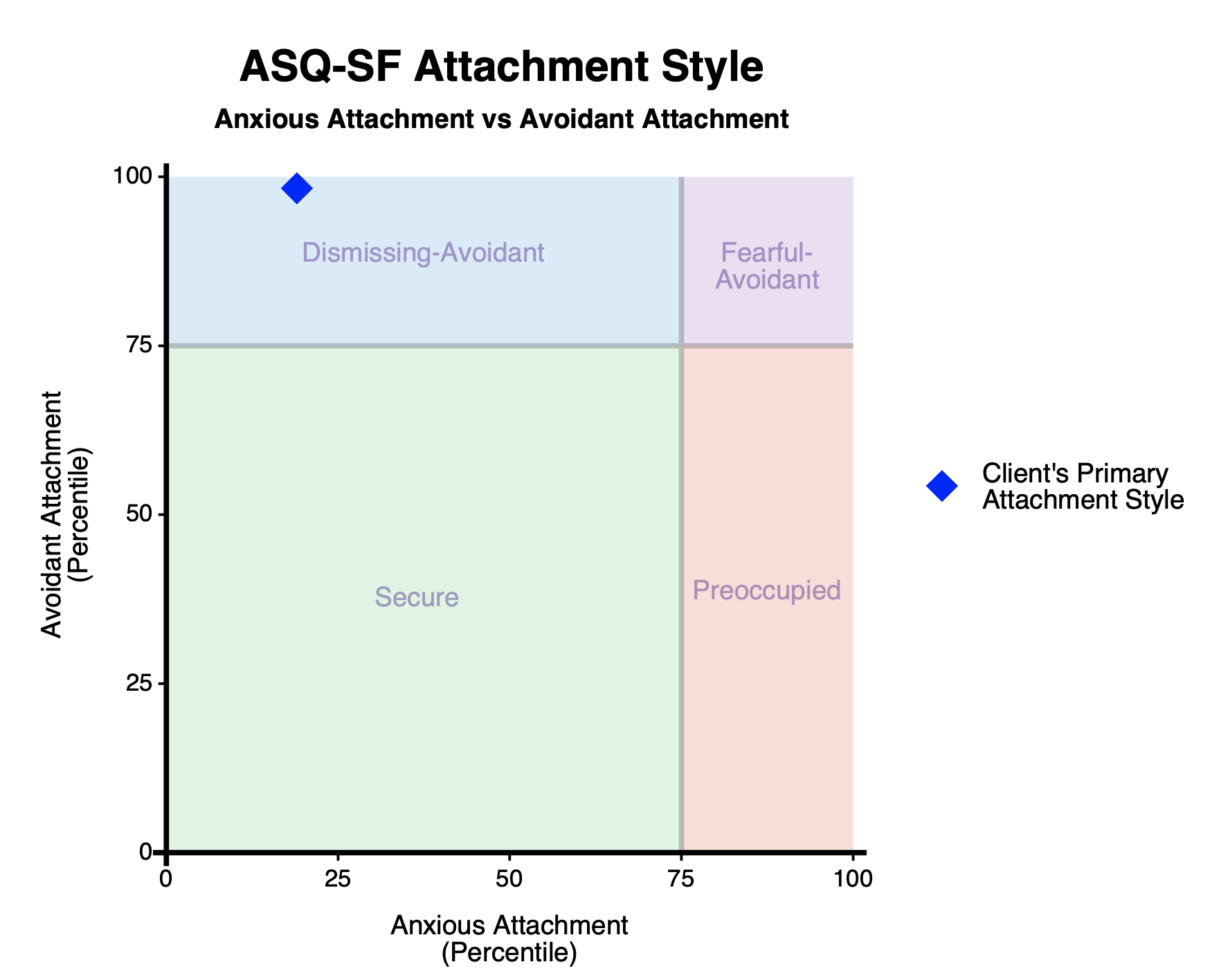

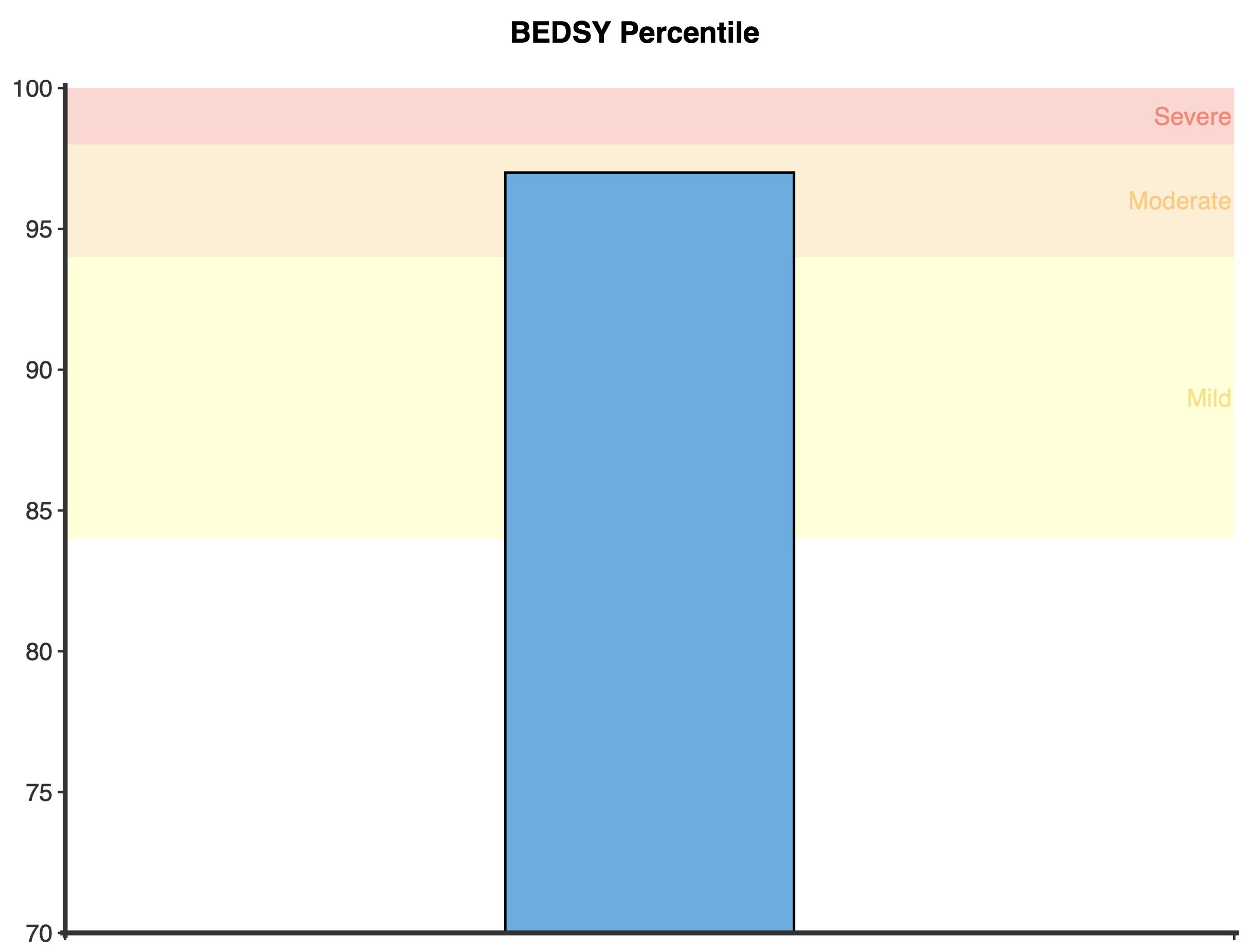

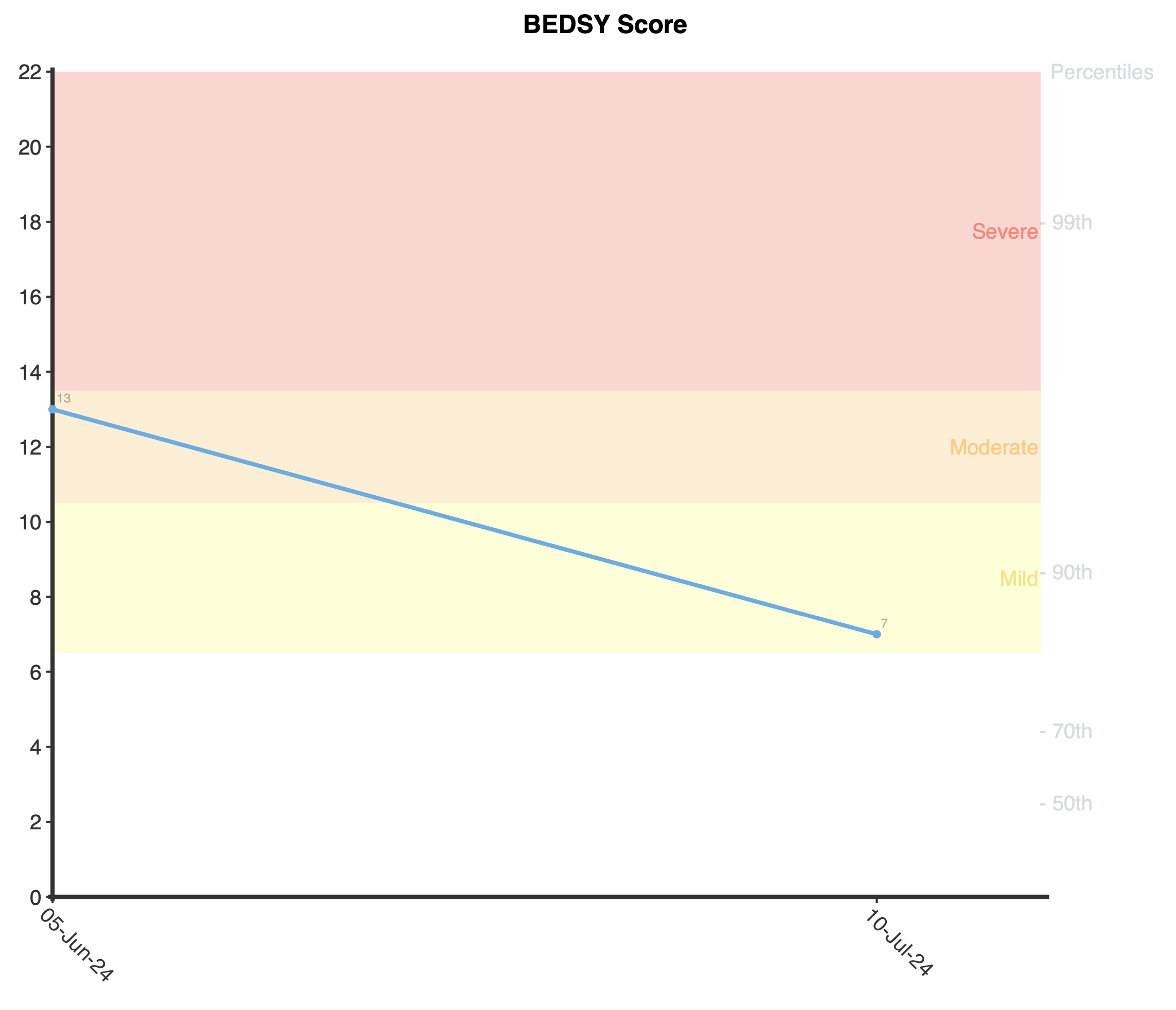

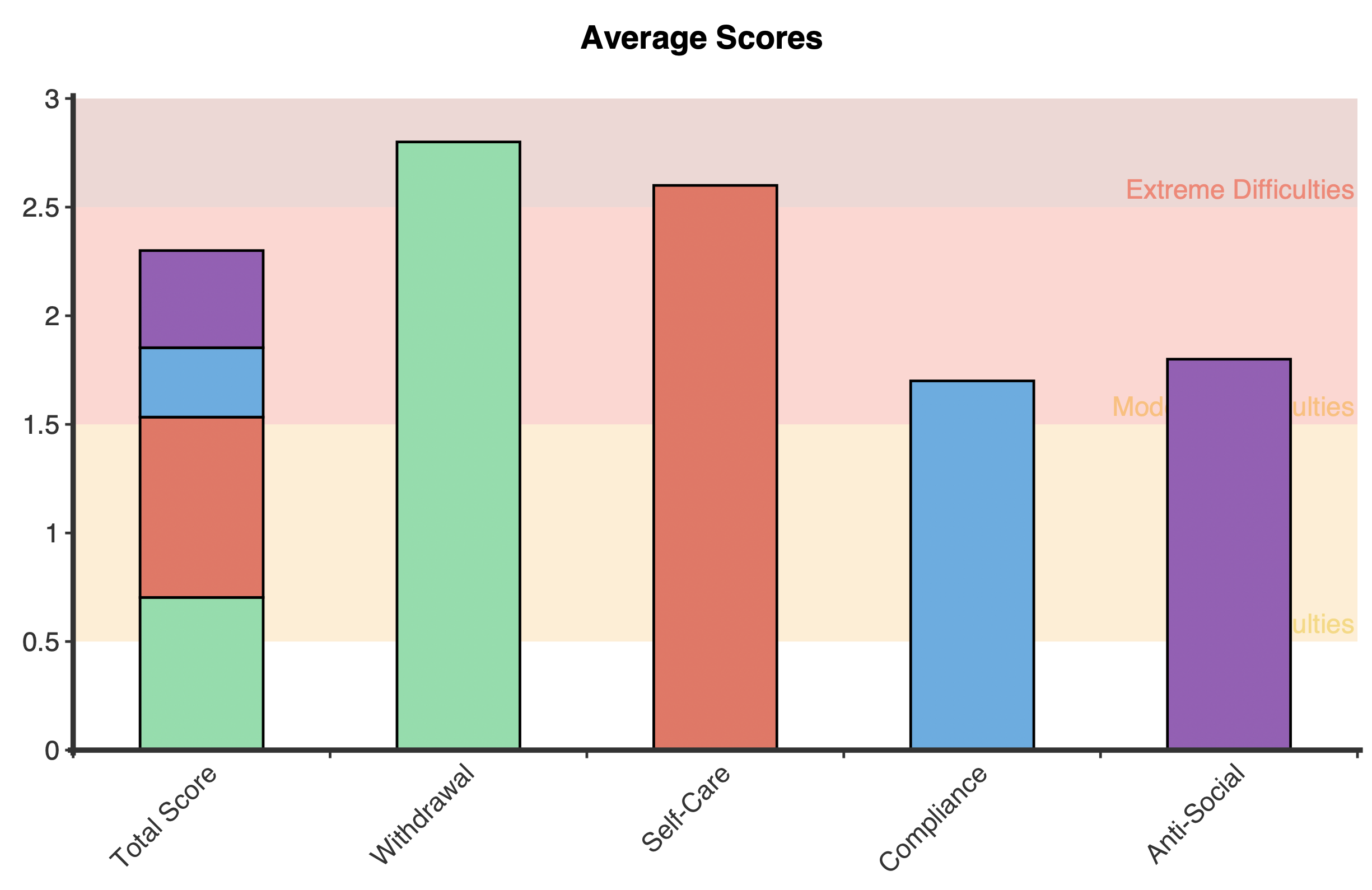

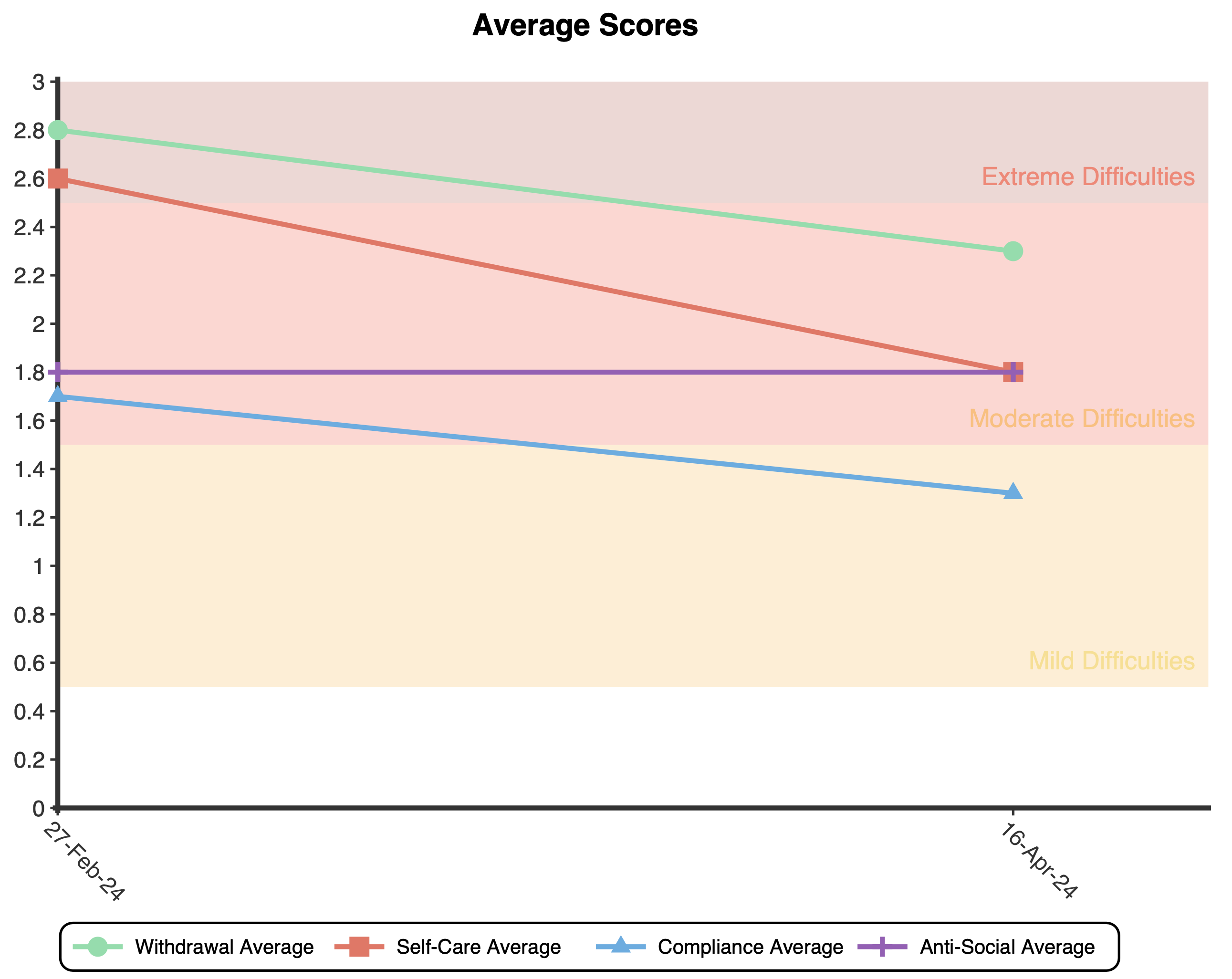

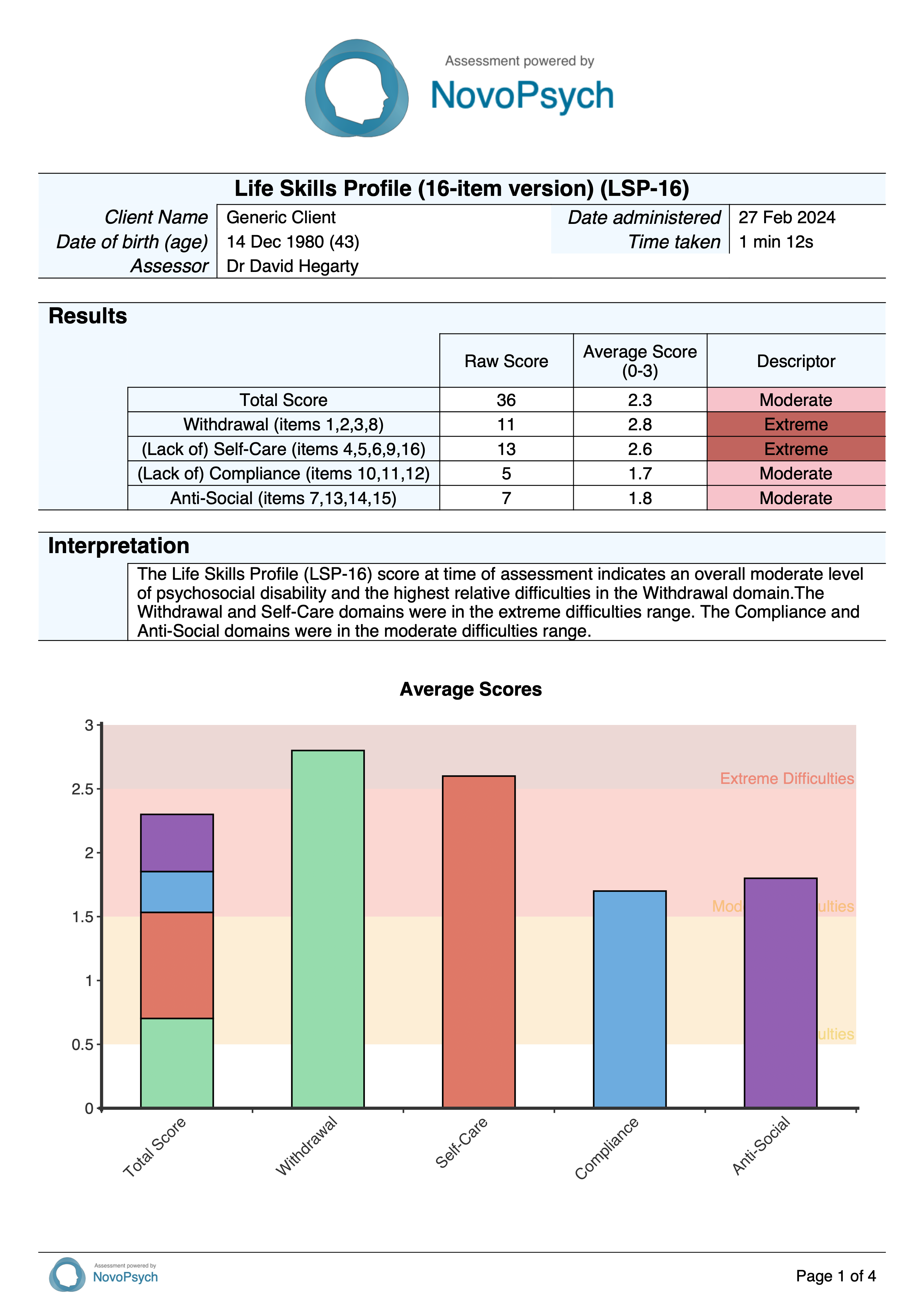

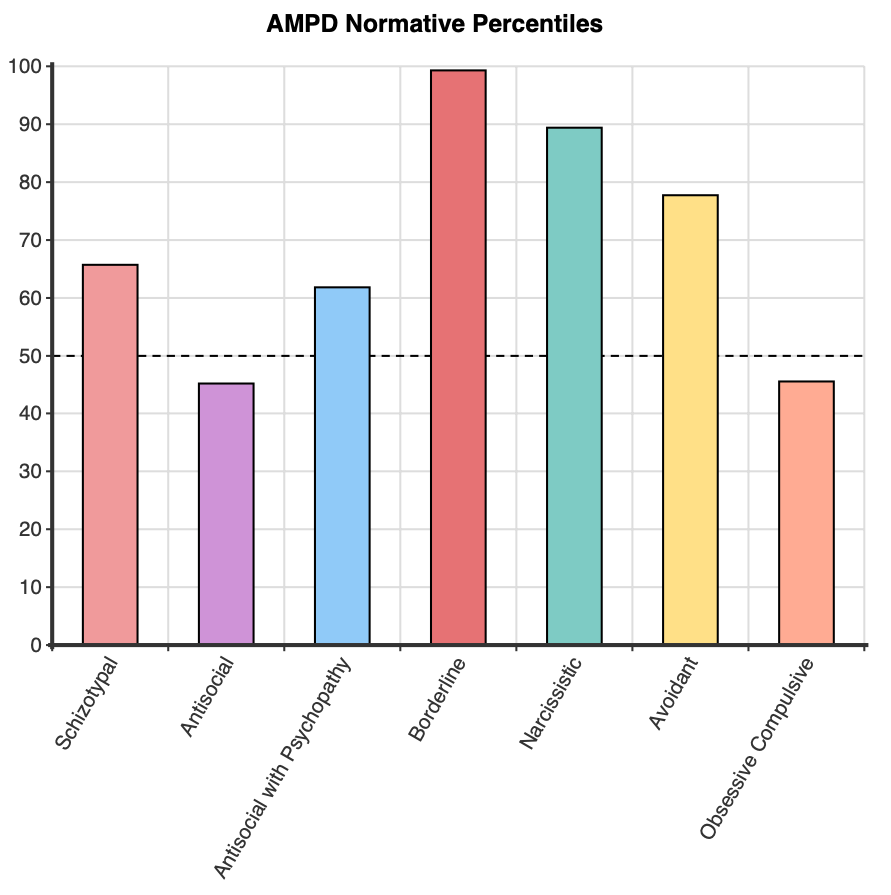

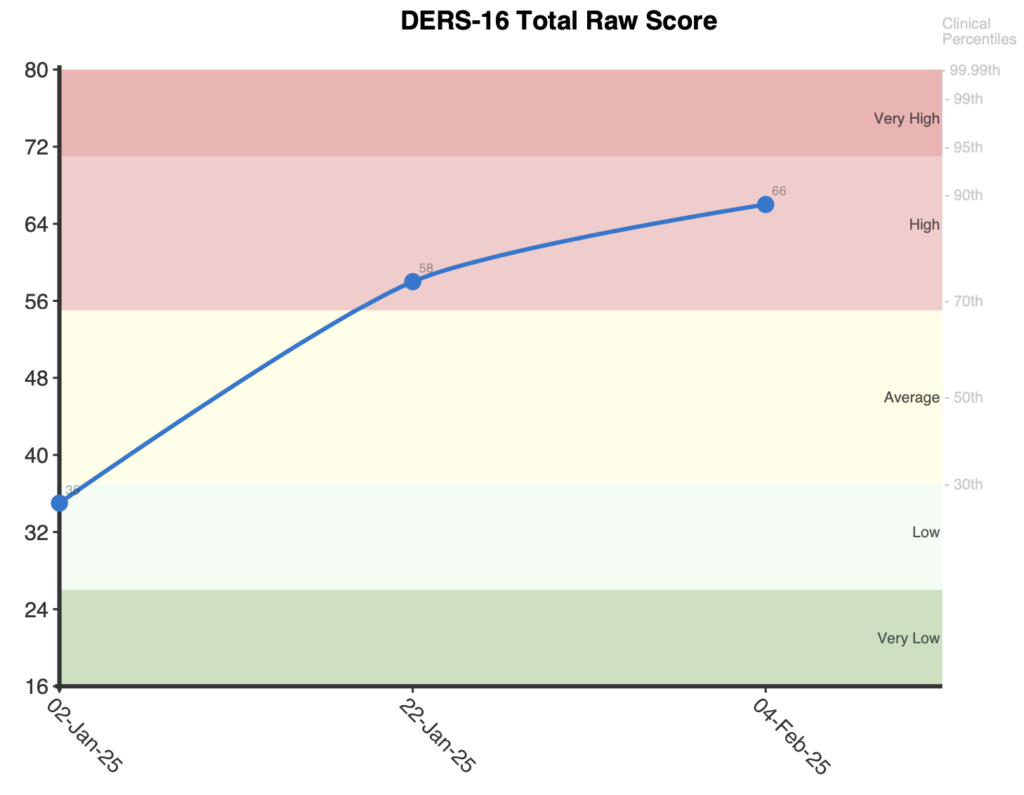

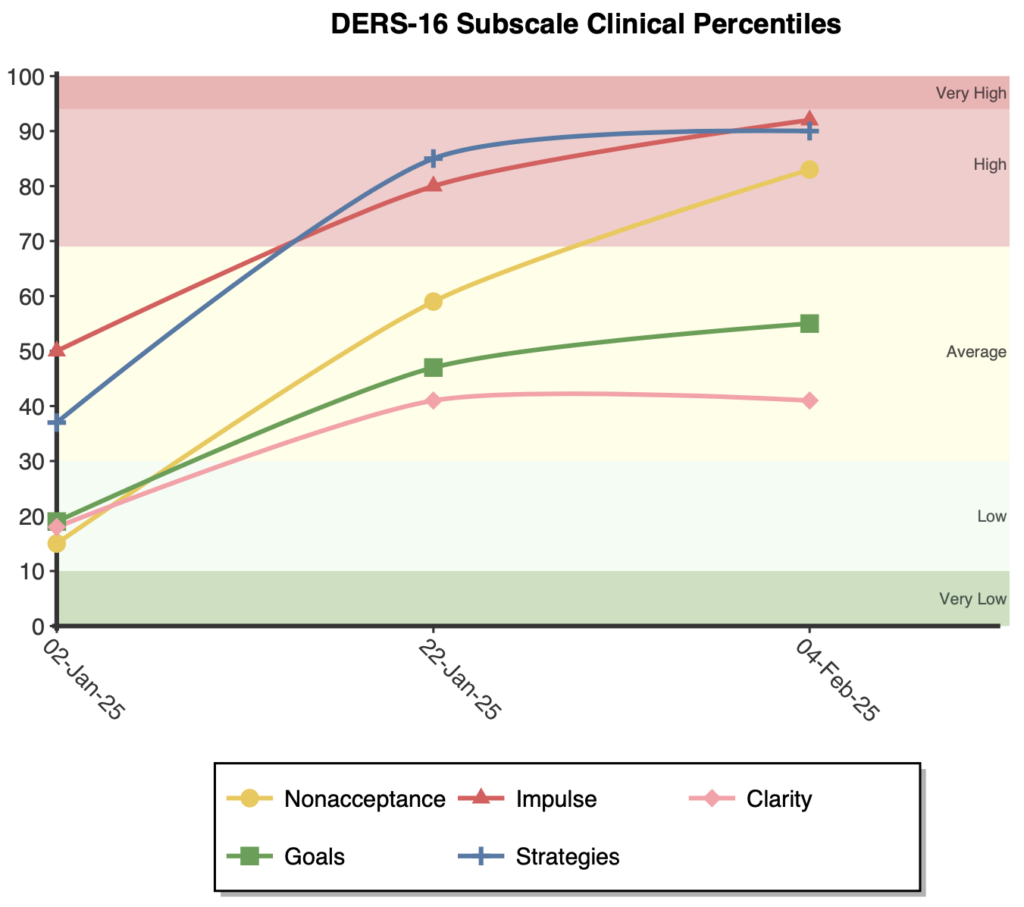

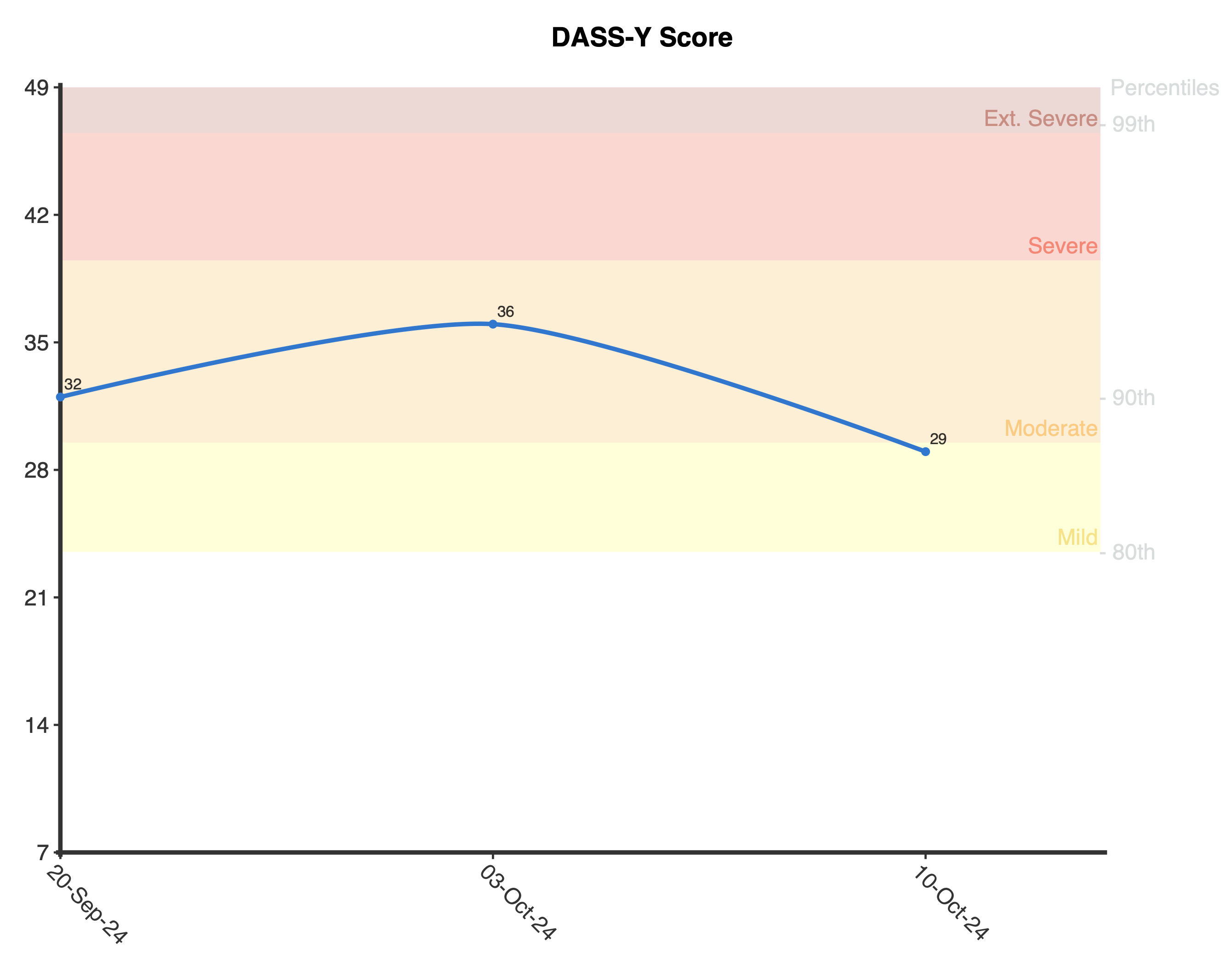

On first administration, a stacked bar graph is presented showing the percentiles for the total score and subscales with the descriptors in the background of the plot. If the scale is administered on multiple occasions, a graph is produced to track emotional intelligence development over time for both the total and the subscale percentiles.

The BEIS-10 was developed by Davies et al. (2010) as a shortened version of the 33-item Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS; Schutte et al., 1998). Internal consistency reliability for the BEIS-10 has been demonstrated across multiple studies, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .74 to .91 for the total scale (Balakrishnan & Saklofske, 2015; Davies et al., 2010; Howell & Miller-Graff, 2014). At the subscale level, reliability coefficients are .60 – .84 for Appraisal of Own Emotions, .67 – .89 for Appraisal of Others’ Emotions, .48 – .84 for Regulation of Own Emotions, .57 – .88 for Regulation of Others’ Emotions, and .67 – .86 for Utilisation of Emotions.

The five-factor structure of the BEIS-10 has been supported through confirmatory factor analysis across multiple studies. Davies et al. (2010) found good model fit for the five-factor solution (CFI = .97, NNFI = .94, RMSEA = .06). This structure was later replicated by Balakrishnan and Saklofske (2015) who reported strong fit indices (CFI = .98, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .04) for the five-factor model.

Research has demonstrated expected relationships between the BEIS-10 and theoretically related constructs. Studies have found moderate negative correlations with neuroticism (r = -.18 to -.32), weak to moderate positive correlations with conscientiousness (r = .15 to .18) and agreeableness (r = .12 to .29), and mixed or non-significant correlations with extraversion and openness to experience. These correlations align with theoretical expectations.

Norms were created for the BEIS-10 total score so that client’s results could be contextualised compared to a community sample. For the normative data a variety of samples were sourced:

- Davies et al. (2010): 955 student athletes in the UK (M = 36.84; SD = 4.43)

- Rizzo & Schwartz (2021): 148 chronic pain patients in the USA (M = 37.10; SD = 7.10)

- Hatamnejad et al. (2023): 405 medical students in Iran (M = 34.60; SD = 6.16)

- Sharma (2024): 120 young adults (18 – 26) in India (M = 36.66; SD = 3.37)

- Coyne (2020): 142 nurses in the USA (M = 40.85; SD = 4.24)

- Balakrishnan & Sakofske (2015): 269 university students in Canada (M = 37.89; SD = 7.74)

- Testa & Sangganjanavanich (2015): 451 counsellors in the USA (M = 41.97; SD = 3.83)

- Moussa & Abdelrehim (2024): 280 students in Egypt (M = 38.41; SD = 4.84)

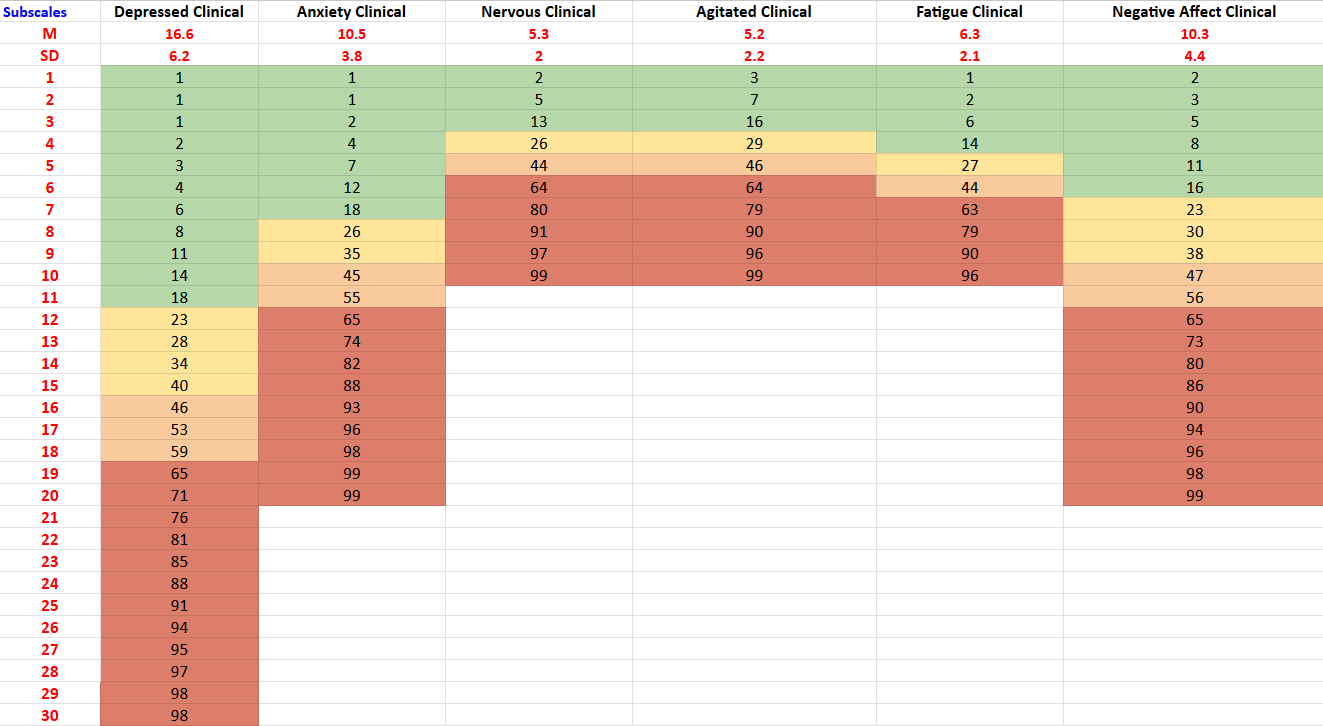

These were combined to provide an overall community sample of 2,770 where the mean was 37.82 and standard deviation was 5.19. The mean and standard deviation are used by NovoPsych to compute community percentiles for overall responses. Some of the aforementioned studies also provided means and standard deviations at the subscale level (Balakrishnan & Saklofske, 2015; Davies et al., 2010; Hatamnejad et al., 2023; Moussa & Abdelrehim, 2024) and these were combined (n = 1,909) to provide percentiles for subscales:

- Appraisal of Own Emotions: M = 7.18; SD = 1.36

- Appraisal of Others’ Emotions: M = 7.42; SD = 1.42

- Regulation of Own Emotions: M = 7.29; SD = 1.42

- Regulation of Others’ Emotions: M = 7.31; SD = 1.36

- Utilisation of Emotions: M = 7.57; SD = 1.39

Percentiles were then used to create descriptors for the total score and subscales of the BEIS-10 as follows:

- 5th percentile and below: Low

- 6th – 24th percentile: Below Average

- 25th – 75th percentile: Average

- 76th – 94th percentile: Above Average

- 95th percentile and above: High

Assess your patients with the Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS-10) using a NovoPsych account

- For Psychologists & Mental Health Clinicians

- Send Assessments to Patient’s Phone

- Receive Comprehensive Reports

- Access Over 100 Validated Assessments

- Instant Psychometric Scoring

- Track Symptoms

- Inform Treatment

Developer

Davies, K. A., Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J., & Scott, J. A. (2010). Validity and reliability of a Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale (BEIS-10). Journal of Individual Differences, 31(4), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000028

References

Balakrishnan, A., & Saklofske, D. H. (2015). Be mindful how you measure: A psychometric investigation of the Brief Emotional Intelligence Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.030

Coyne, K. A. D. (2020). Nurses Caring for Pregnant Women with Substance Use Disorder: Exploring Emotional Intelligence and Attitude. [Doctoral dissertation, Carlow University], https://www.proquest.com/openview/d18c93212c25aa943a053f78e917a72a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=51922&diss=y

Hatamnejad, M. R., Hosseinpour, M., Shiati, S., Seifaee, A., Sayari, M., Seyyedi, F., Lankarani, K. B., & Ghahramani, S. (2023). Emotional intelligence and happiness in clinical medical students: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Health Science Reports, 6(12), e1745. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1745

Moussa, M. A., & Abdelrehim, H. A. (2024). An evaluation study of emotional intelligence structure according to the ability and traits perspectives among university students. Port Said Journal of Educational Research, 3(2), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.21608/psjer.2024.265051.1033

Rizzo, J. M., & Schwartz, R. C. (2021). The effect of mindfulness, psychological flexibility, and emotional intelligence on self-efficacy and functional outcomes among chronic pain clients. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 51(2), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-020-09481-5

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/dugg-p24e-52wk-6cdg

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00001-4

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E. (2007). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(6), 921–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.003

Sharma, S. (2024). Impact of Emotional Intelligence and Resilience and Life Satisfaction among Young Adults. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Approaches in Psychology, 2(5). https://www.psychopediajournals.com/index.php/ijiap/article/view/433

Van Rooy, D. L., & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-8791(03)00076-9

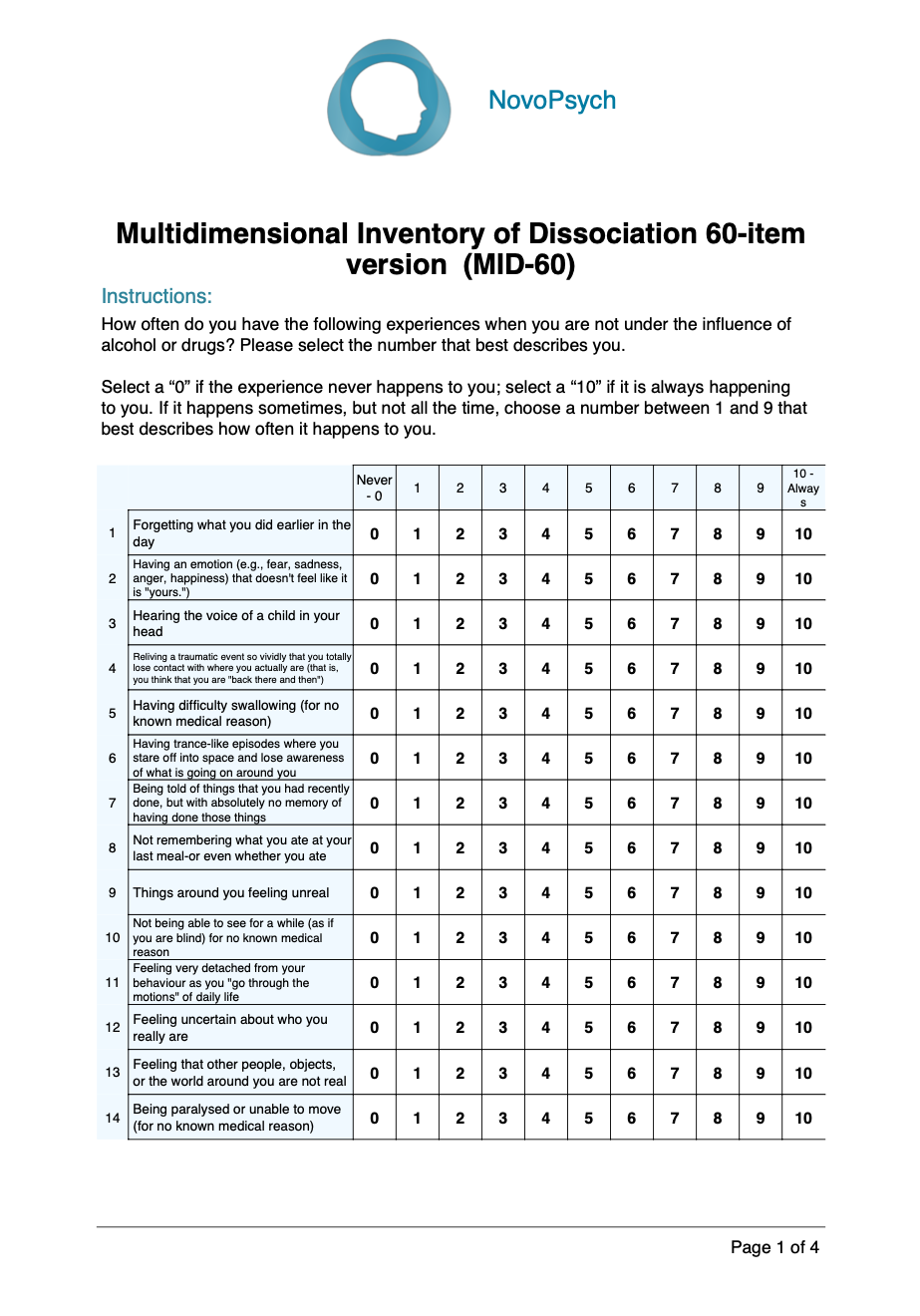

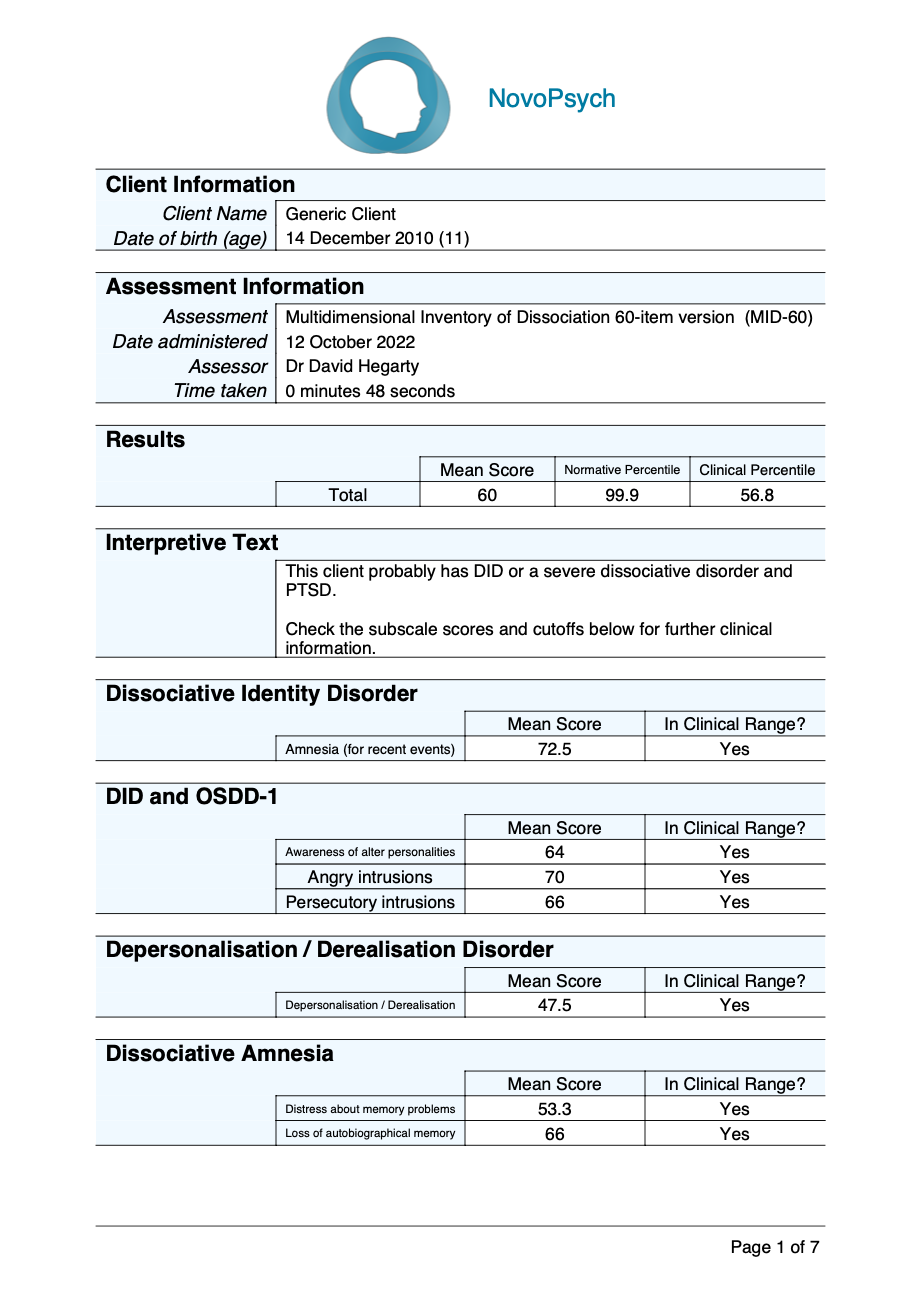

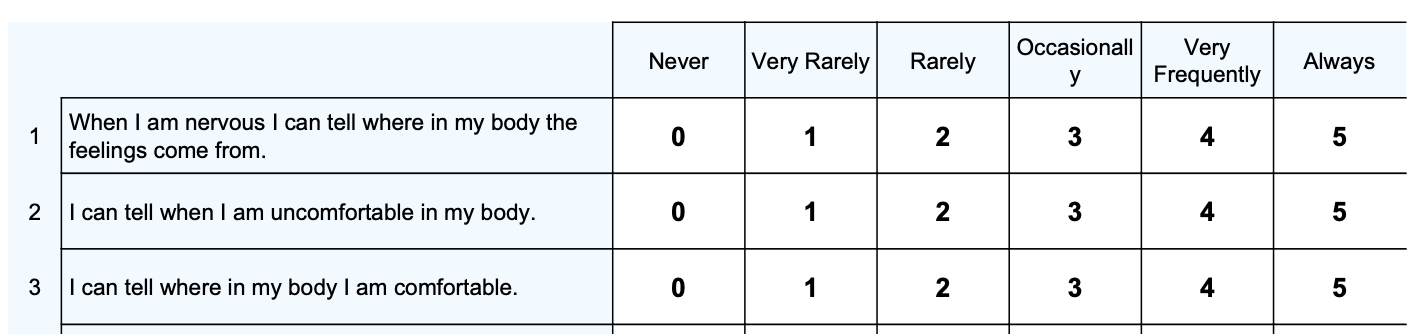

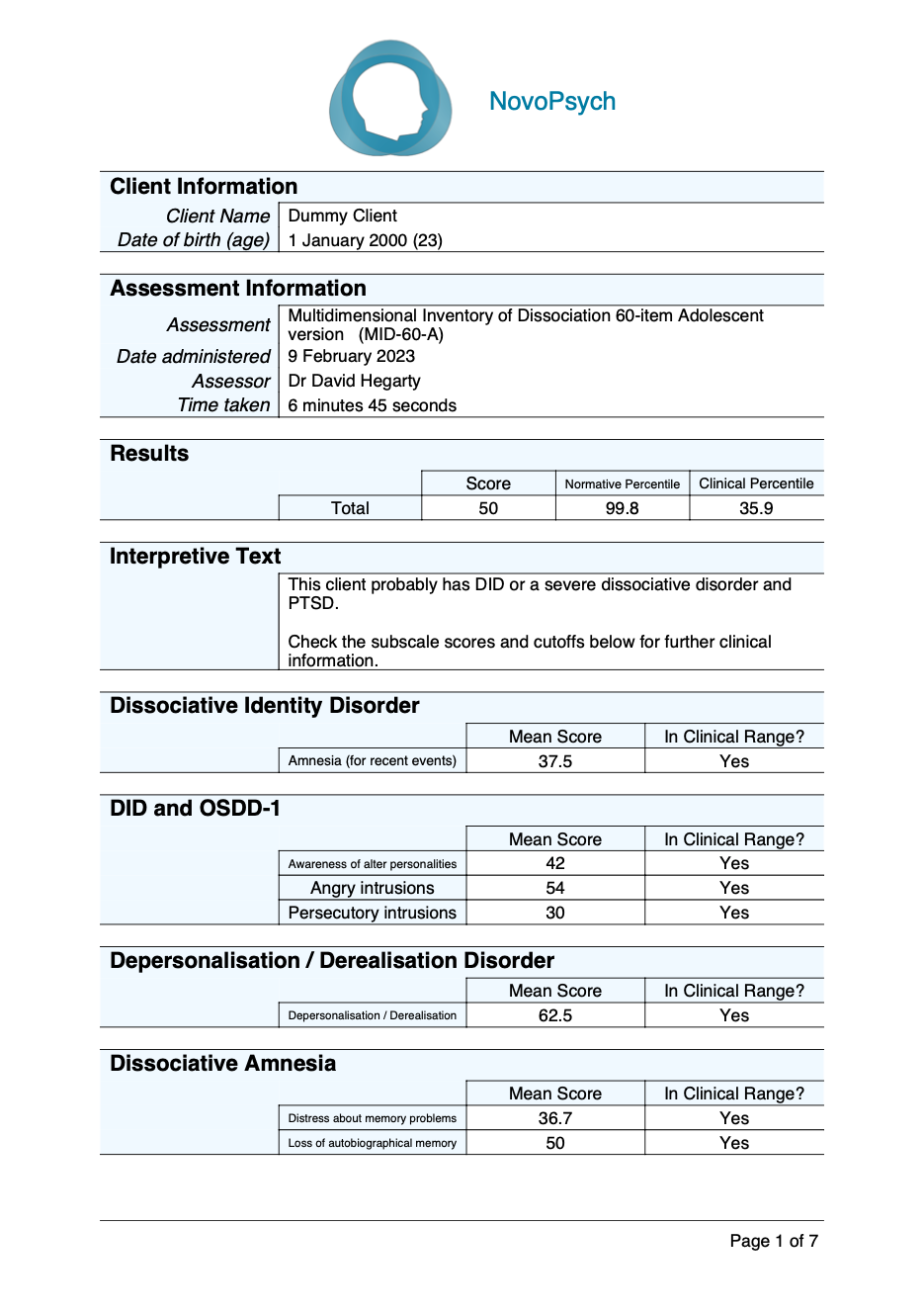

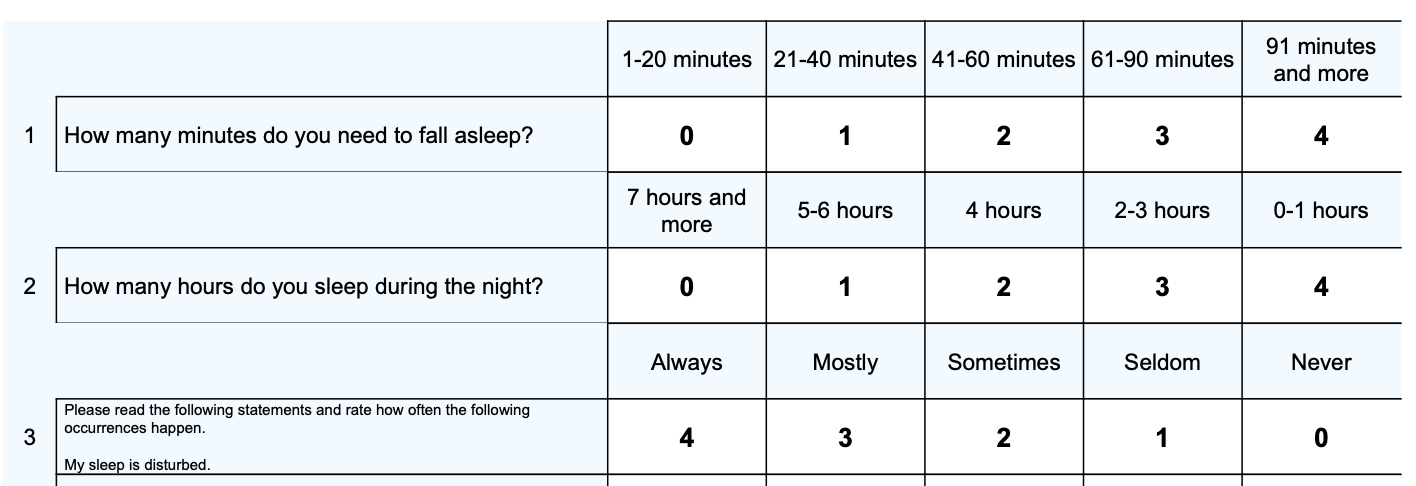

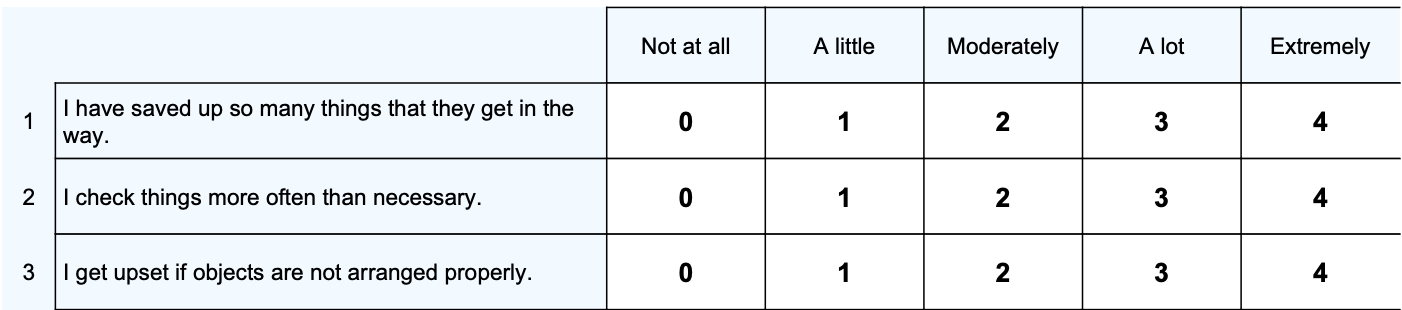

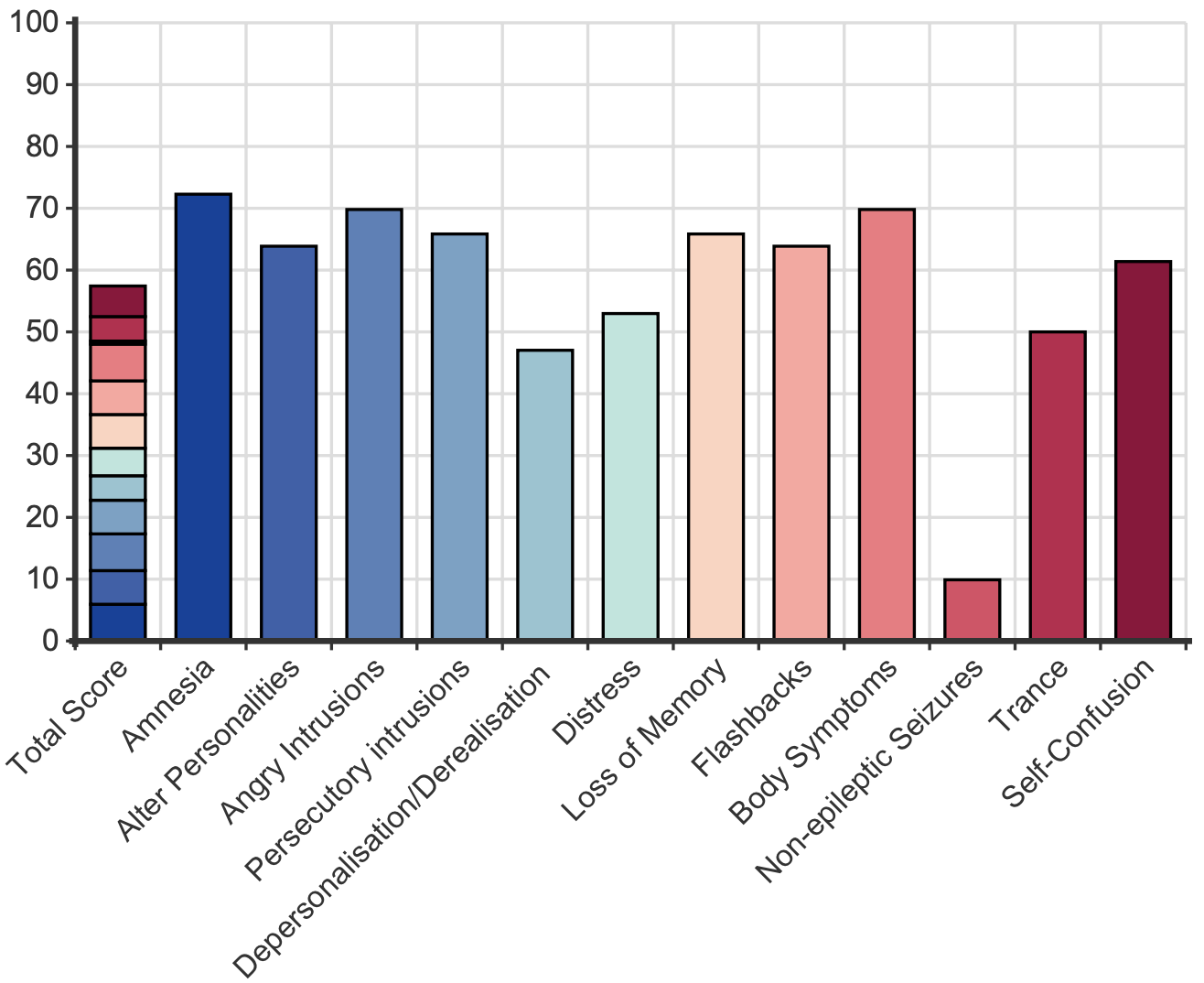

Scores for each item range from zero (never) to 10 (always). The MID-60 mean score represents the percentage of time the person self-reports having dissociative symptoms and experiences. Hence, a person with dissociative identity disorder may have dissociative symptoms and experiences around half the time (51%) whereas for a university student this may be 13% of the time. A mean score of more than 21% indicates clinically significant symptoms.

Scores for each item range from zero (never) to 10 (always). The MID-60 mean score represents the percentage of time the person self-reports having dissociative symptoms and experiences. Hence, a person with dissociative identity disorder may have dissociative symptoms and experiences around half the time (51%) whereas for a university student this may be 13% of the time. A mean score of more than 21% indicates clinically significant symptoms.