The Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation 60-item version (MID-60) is a screening tool for adults (18 years +) that assesses dissociative symptoms and experiences specific to DSM-5-TR dissociative disorders. It also captures dissociative experiences, PTSD and somatic symptoms, and phenomena closely related to dissociation such as trance and self-confusion. There is also an adolescent version for use with adolescents ages 16 to 19 years of age – the MID-60-A.

Dissociation is an adaptive defence in response to high stress or trauma that is characterised by memory loss, depersonalisation, derealisation, identity confusion, and identity alteration. Around 10% of the population will meet criteria for a dissociative disorder during their lifetime (Kate, Hopwood, Jamieson, 2020).

The MID-60 has 12 subscales, which are presented here according to the diagnostic category the subscale is most aligned to:

Clients who are completing the MID-60 at home may benefit from further instructions available here.

Scores for each item range from zero (never) to 10 (always). The MID-60 mean score represents the percentage of time the person self-reports having dissociative symptoms and experiences. Hence, a person with dissociative identity disorder may have dissociative symptoms and experiences around half the time (51%) whereas for a university student this may be 13% of the time. A mean score of more than 21% indicates clinically significant symptoms.

Scores for each item range from zero (never) to 10 (always). The MID-60 mean score represents the percentage of time the person self-reports having dissociative symptoms and experiences. Hence, a person with dissociative identity disorder may have dissociative symptoms and experiences around half the time (51%) whereas for a university student this may be 13% of the time. A mean score of more than 21% indicates clinically significant symptoms.

Interpretation of MID-60 mean scores is consistent with the 218-item MID. Specifically:

Subscales

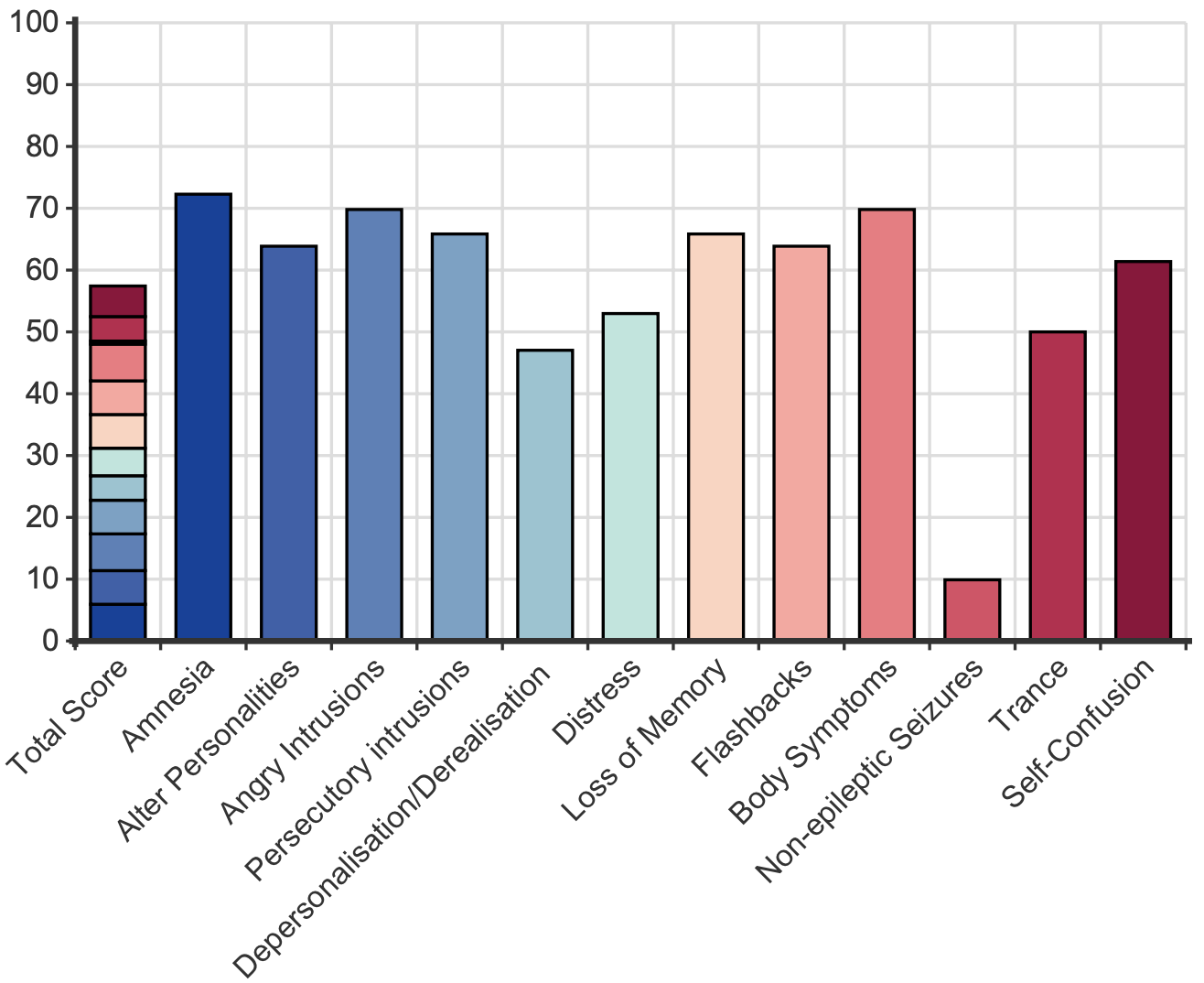

The MID-60 provides information on subscales relevant to different diagnoses. This enables the clinician to form an impression about the likely diagnosis. For example, a score of 27% is clinically significant, but does not indicate the most likely diagnosis. If the subscales of PTSD and depersonalisation/derealisation are both above the clinical threshold, this can indicate the person has the dissociative subtype of PTSD, whereas if the memory-related subscales are above the clinical threshold this can indicate dissociative amnesia. Another example is a person who scores 45%, which would seem to indicate dissociative identity disorder. Yet, if the subscale score for amnesia (for recent events) is not elevated, this points towards a more severe case of other specified dissociative disorder. The subscales are:

The MID-60 is for screening purposes, is not designed to be the sole determinant of a diagnosis and should always be used in conjunction with clinical expertise. Further evaluations can be conducted with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D) or Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS).

The MID-60 is a short version of the 218-item Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation, a diagnostic instrument (Dell, 2006). The MID-60 was derived from the five items with the highest pattern matrix loading for each of the MID’s 12 factors (Dell & Lawson, 2009). The MID-60 has a nearly identical factor structure to the full MID, excellent internal reliability (α = .97) and content and convergent validity (Kate et al., 2020).

Normative sample

The mean score for both males and females in an Australian university sample (n = 313) was 13.0 (SD = 13.8; Kate et al., 2021). Age did not moderate mean scores MID-60. However, younger participants aged 24 or under had significantly higher scores on the subscales of self-confusion (19.3 vs. 14.6) and angry intrusions (10.0 vs. 6.6).

Clinical samples

Females with a dissociative disorder diagnoses (N = 30) had a mean MID-60 score of 56.8 (SD = 18.8) and the two males had a mean score of 53.4 (SD = 4.7; Kate, Jamieson & Middleton, 2021; 2022). This is consistent with the mean for the 218-item MID, i.e., DID (N = 76, M = 51.3, SD = 18.7) and OSDD-1 (N = 40, M = 39, SD 19.4; Dell et al., 2017). The MID mean has been calculated in people with schizophrenia experiencing a relapse (N = 20, M = 27.0, SD = 20.6) and in remission (N = 20, M = 18.4, SD = 19.2; Laddis & Dell, 2012) and in a clinical group with a borderline personality disorder diagnosis (N = 21, M = 25.4, SD = 18.1, Korzekwa et al., 2009).

Developer

Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., Dorahy, M. J., & Middleton, W. (2021). Measuring Dissociative Symptoms and Experiences in an Australian College Sample Using a Short Version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 22(3), 265-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2020.1792024

Dell, P. F. (2006). The Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation (MID): A Comprehensive measure of pathological dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(2), 77-106.

Dell, P. F., Coy, D. M., & Madere, J. (2017). An Interpretive Manual for the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation (MID). In (2nd ed.). https://www.mid-assessment.com/request-mid-analysis/

Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., & Middleton, W. (2021). Childhood Sexual, Emotional, and Physical Abuse as Predictors of Dissociation in Adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1955789

Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., & Middleton, W. (2022). Parent-child dynamics as predictors of dissociation in adulthood. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Psychological Sciences, Southern Cross University.

Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., Dorahy, M. J., & Middleton, W. (2021). Measuring Dissociative Symptoms and Experiences in an Australian College Sample Using a Short Version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 22(3), 265-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2020.1792024

Kate, M.-A., Hopwood, T., & Jamieson, G. (2020). The prevalence of Dissociative Disorders and dissociative experiences in college populations: a meta-analysis of 98 studies. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(1), 16-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2019.1647915

Korzekwa, M. I., Dell, P. F., Links, P. S., Thabane, L., & Fougere, P. (2009). Dissociation in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Detailed Look. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 10(3), 346-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299730902956838

Laddis, A., & Dell, P. F. (2012). Dissociation and Psychosis in Dissociative Identity Disorder and Schizophrenia. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(4), 397-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2012.664967

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved