The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – short form (PID-5-SF) is a measure designed to assess dysfunctional personality traits according to the conceptual framework proposed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). It is a concise version of the original PID-5 (Krueger et al., 2012) and consists of 100 items that measure five broad domains of personality dysfunction, which are then further divided into 25 facets, capturing specific aspects of personality functioning (Maples et al., 2015).

The PID-5-SF presents personality traits in two district methods. An empirically derived framework with five personality domains, and a seven personality domains framework that aligns with DSM-5-TR conceptualisation of personality pathology.

The five empirically derived personality factors (and the facets that contribute to them) are:

The DSM-5-TR aligning framework known as the Alternative Model of Personalities (AMPD), includes the following domains:

The Alternative Model of Personalities (AMPD) composite scores align with the dimensional trait model proposed in Section III of the DSM-5 and DMS-5-TR. The AMPD composite scores are derived from specific combinations of PID-5-SF facets that represent broader dimensions of personality functioning: The use of AMPD composite scores can be useful for clinicians in several ways. Firstly, it helps in diagnosing personality disorders in a more comprehensive, systematic and dimensional manner. By focusing on impairments in personality functioning and specific traits, clinicians can better capture the nuances and variations in personality pathology, leading to more accurate and personalised treatment planning. Research by Bach et al. (2015) supports the clinical utility of the AMPD model for diagnosing personality disorders in a dimensional approach.

Secondly, AMPD composite scores offer a standardised and quantifiable way of measuring personality dysfunction. This allows for easier comparison and communication among different clinicians and researchers, enhancing the consistency and reliability of personality assessment in both clinical and research settings.

Overall, the PID-5-SF enables a comprehensive evaluation of an individual’s personality traits and helps in identifying maladaptive patterns that may be indicative of various psychopathologies. By using a standardised measure like the PID-5-SF, clinicians can better assess and compare their clients’ personality traits across different diagnostic categories, leading to more accurate and reliable diagnoses. Additionally, the PID-5-SF offers a dimensional approach to personality assessment, allowing clinicians to capture the subtleties and variations in personality functioning rather than relying solely on categorical diagnoses. This dimensional approach is supported by research, such as that conducted by Krueger et al. (2012), which highlights the advantages of utilising personality trait measures for a more nuanced understanding of psychopathology.

As well as the major personality domains presented above, there are also 25 facets measured by the PID-5-SF. These facets represent specific dimensions of personality functioning, providing a detailed understanding of an individual’s personality traits and potential areas of concern. They are:

Anhedonia, Anxiousness, Attention Seeking, Callousness, Deceitfulness, Depressivity, Distractibility, Eccentricity, Emotional Lability, Grandiosity, Hostility, Impulsivity, Intimacy Avoidance, Irresponsibility, Manipulativeness, Perceptual Dysregulation, Perseveration, Restricted Affectivity, Rigid Perfectionism, Risk Taking, Separation Insecurity, Submissiveness, Suspiciousness, Unusual Beliefs and Experiences, and Withdrawal.

Scoring and interpretation of the PID-5-SF involves summing the item responses within each facet and domain to obtain average scores (between 0 and 3). Higher average scores indicate elevated levels of specific personality traits, while average scores indicate relatively lower expression of those traits.

The PID-5-SF assesses five broad domains of personality traits, each representing distinct patterns of behaviour, emotions, and interpersonal functioning:

The PID-5-SF can also be used to determine Alternative Model of Personalities (AMPD) composite scores, which align with more traditional diagnostic labels, and is consistent with the dimensional trait model proposed in Section III of the DSM-5 and consistent with the DSM-5-TR:

The 25 facets capture specific dimensions of personality functioning, providing a detailed understanding of an individual’s personality traits and potential areas of concern.:

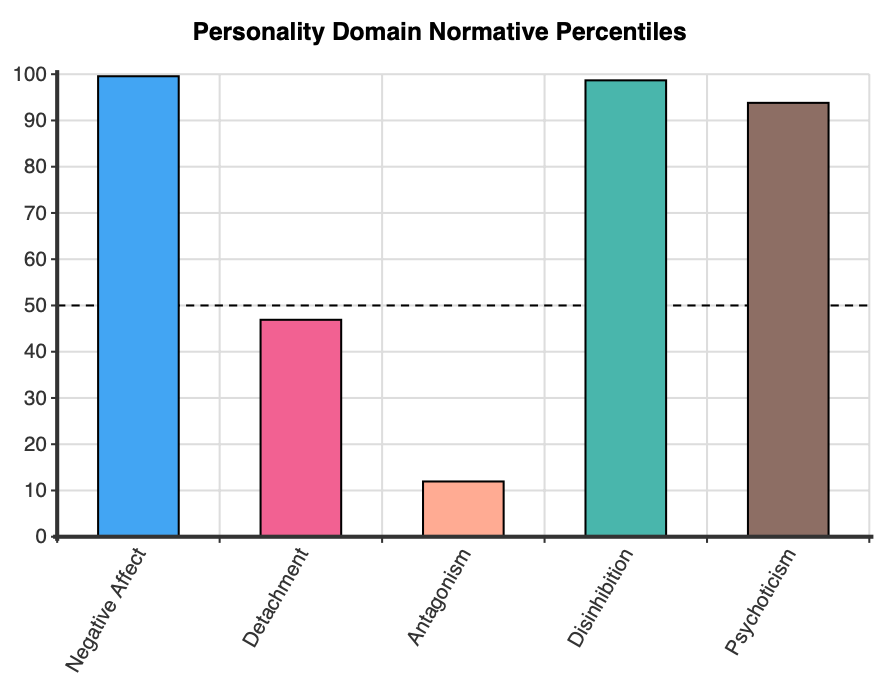

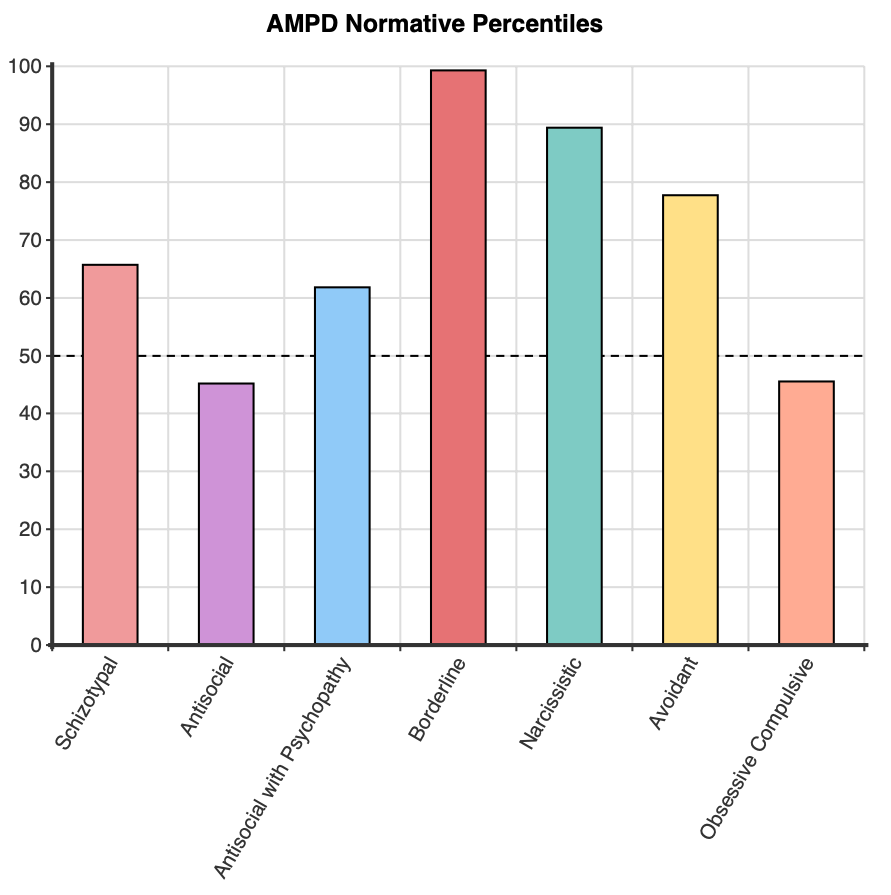

Normative percentiles, which compare the respondent’s score to those of a adult normative sample are presenting (Miller et al’s (2022) analysis of Krueger et al’s (2012) data). These percentiles allow the clinician to contextualise where their client’s scores sit in comparison to a normative group. For example, a percentile of 50 is indicative of an average level of that trait or personality domain when compared to the normative group. In contrast, a percentile of 90 indicates scores above 90% of the adult population, and is therefore likely to be of clinical significance. Plots are shown for the personality domain and AMPD percentiles, with a dotted line at 50 which indicates an average level in comparison to the normative group.

The PID-5-SF has been subject to extensive psychometric evaluation to assess its reliability and validity. Factor analysis suports the five-factor structure of the PID-5-SF, which corresponds to the five domains: Negative Affectivity, Detachment, Antagonism, Disinhibition, and Psychoticism (Maples et al., 2015). The PID-5-SF showed adequate internal consistency with alpha coefficients ranging from .89 to .91 (trait domains) and .74 to .88 (trait facets) with means of .90 and .83, respectively (Maples et al., 2015).

The validity of the PID-5-SF has been supported by several lines of evidence, with the PID-5-SF domains and facets aligning well with the proposed DSM-5 model of personality traits (Maples et al., 2015). Convergent validity has been demonstrated by examining the relationships between PID-5-SF scores and the NEO-PI-R and the International Personality Item Pool (Krueger et al., 2012). Additionally, the PID-5’s AMPD have demonstrated discriminant validity by differentiating between individuals with and without personality disorders and various psychopathological conditions (Bach et al., 2015).

The factor structure of the PID-5-SF was highly similar to the original PID-5 (congruency coefficients from .93 to .99; Maples et al., 2015). The convergent correlations ranged for the domains from .96 to .98 (mean .97) and from .89 to 1.0 (mean .94) for the facets. The similarity of the discriminant validity of the PID-5 and the PID-5-SF (the pattern of the correlations of a given domain with the four other domains) was .98. These findings suggest that the domains, facets, and DSM-5 AMPD traits can be reliably and validly measured with the PID-5-SF and provide similar results to the PID-5 (Thimm et al., 2016).

Normative data were obtained for the PID-5 by Miller et al. (2022). As average scores are used for these norms, the means and standard deviations are transferred for use within each Personality Domain, Facet, and AMPD in the PID-5-SF to calculate percentiles. The normative sample was derived from Krueger et al’s (2012) representative sample of 1,392 adults in the United States (44.2% male; 55.8% female).

Maples, J. L., Carter, N. T., Few, L. R., Crego, C., Gore, W. L., Samuel, D. B., Williamson, R. L., Lynam, D. R., Widiger, T. A., Markon, K. E., Krueger, R. F., & Miller, J. D. (2015). Testing whether the DSM-5 personality disorder trait model can be measured with a reduced set of items: An item response theory investigation of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 . Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1195–1210. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000120

Bach, B., Markon, K., Simonsen, E., & Krueger, R. F. (2015). Clinical utility of the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders: six cases from practice. Journal of psychiatric practice, 21(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000460618.02805.ef

Krueger, R. F., Derringer, J., Markon, K. E., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. E. (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological medicine, 42(9), 1879–1890. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002674

Miller, J. D., Bagby, R. M., Hopwood, C. J., Simms, L. J., & Lynam, D. R. (2022). Normative data for PID-5 domains, facets, and personality disorder composites from a representative sample and comparison to community and clinical samples. Personality disorders, 13(5), 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000548

Thimm, J. C., Jordan, S., & Bach, B. (2016). The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 Short Form (PID-5-SF): psychometric properties and association with big five traits and pathological beliefs in a Norwegian population. BMC psychology, 4(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0169-5

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved