Dr David Hegarty

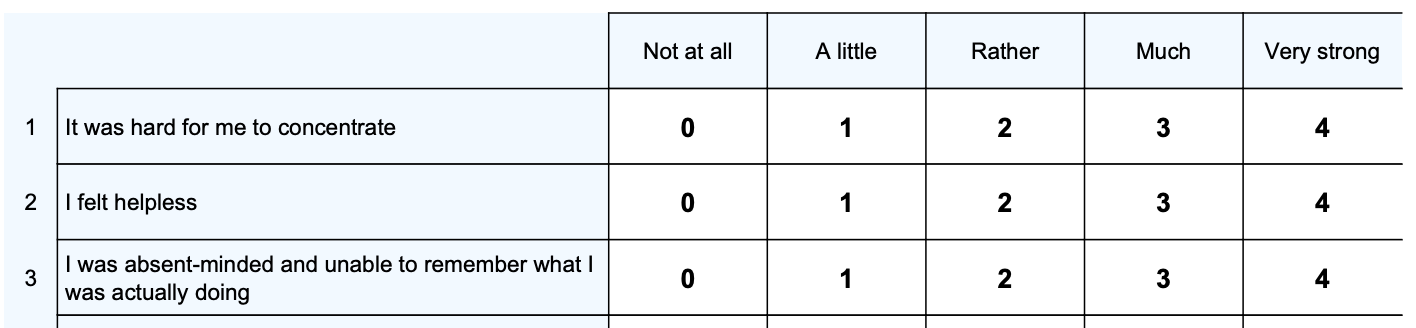

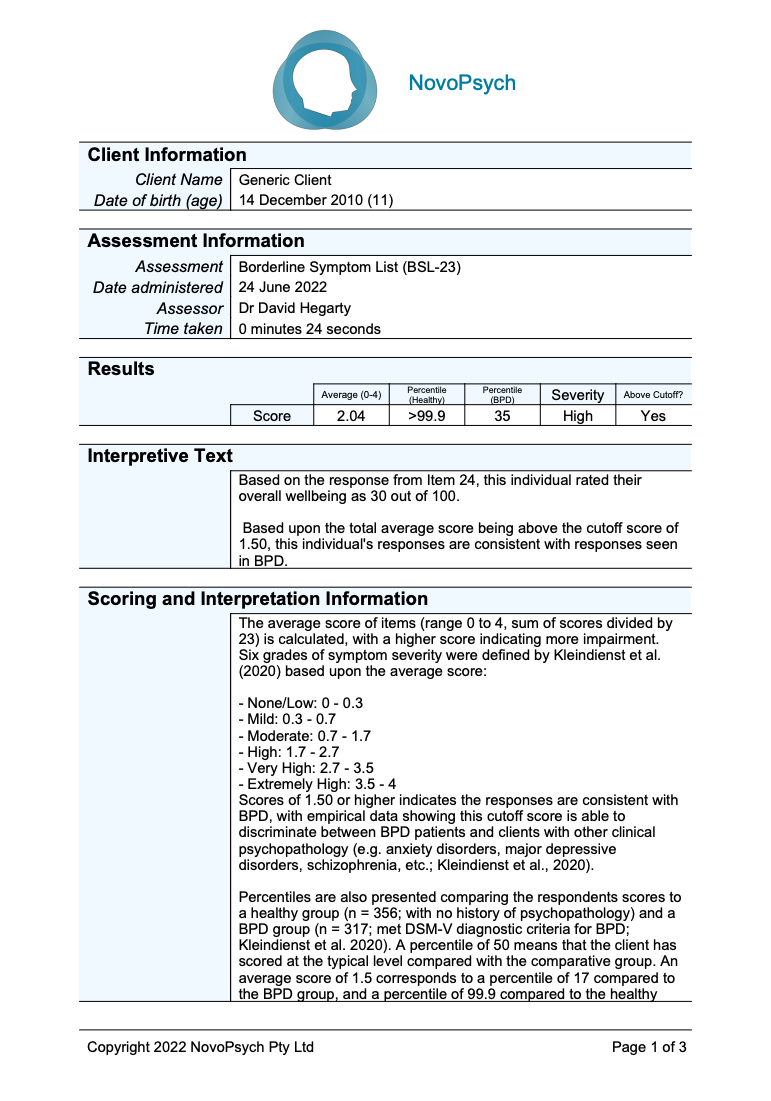

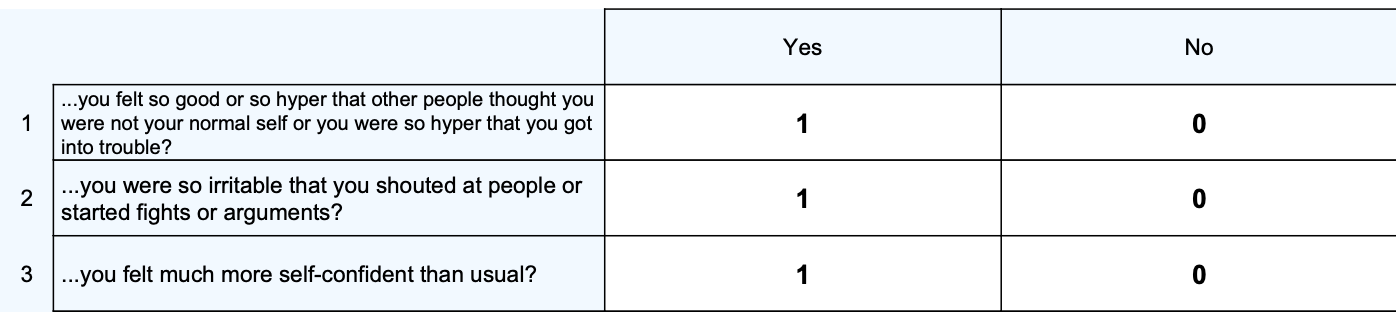

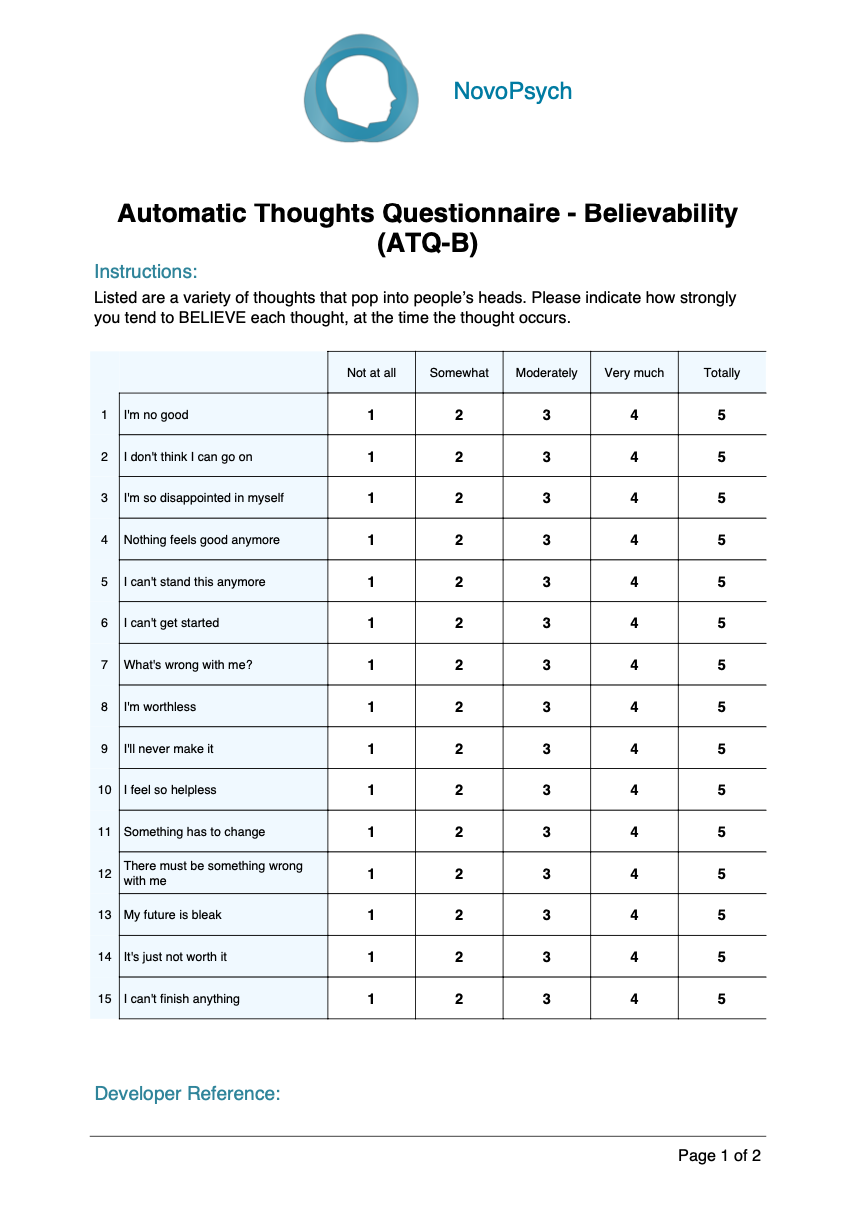

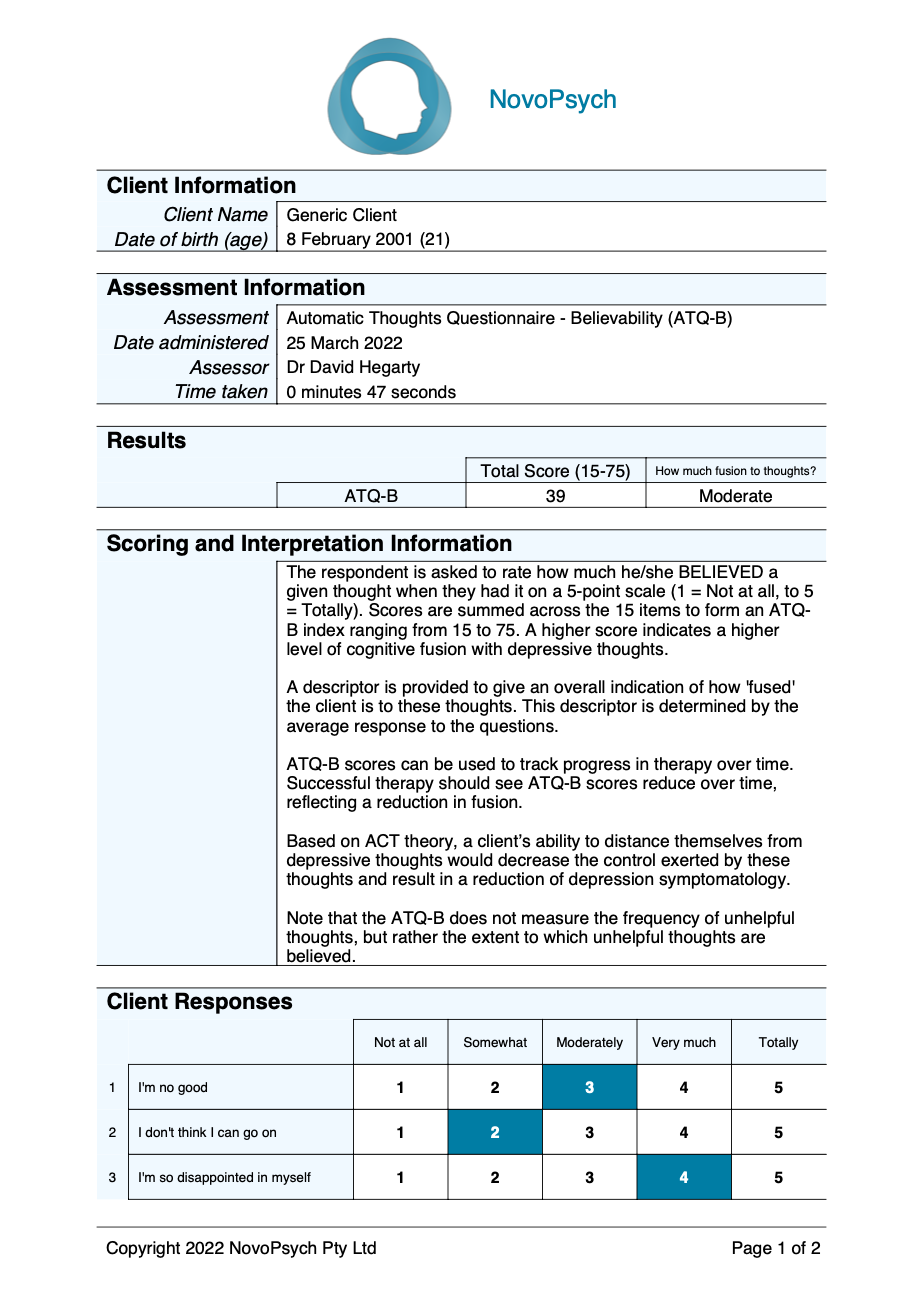

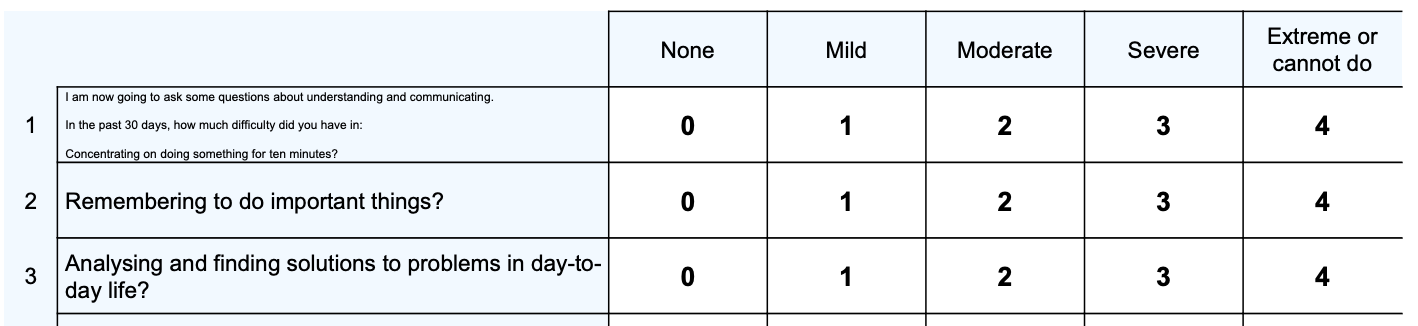

The Borderline Symptom List – Short Version (BSL-23) is a 23-item self-rating instrument for specific assessment of borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptomatology in adults (18+). The scale assesses DSM BPD diagnostic criteria (e.g., affective instability, recurrent suicidal behaviour, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behaviour, and transient dissociative symptoms) in addition to items that are based on borderline-typical empirical findings regarding self-criticism, problems with trust, emotional vulnerability, and proneness to shame, self-disgust, loneliness, and helplessness (Kleindienst et al., 2020).

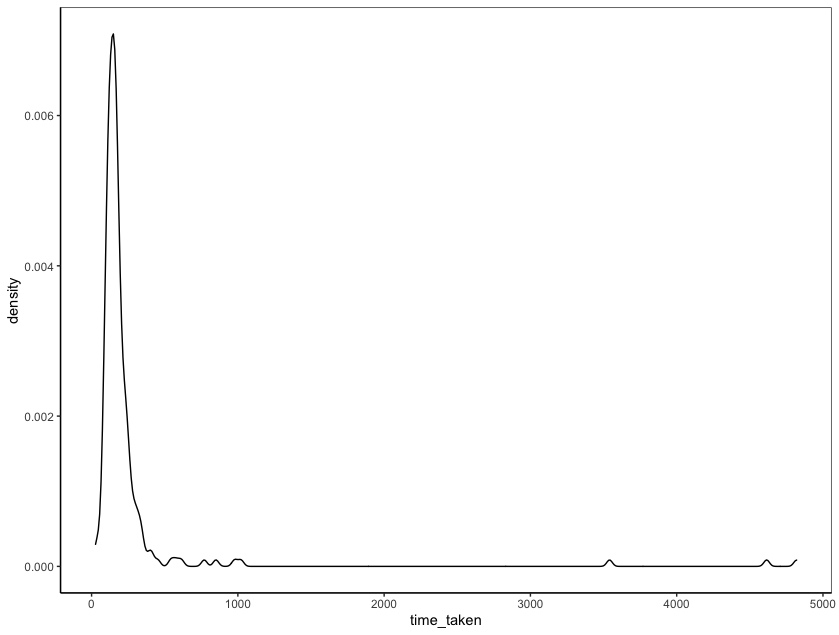

- 4 minutes

- Ages 18+

- Diagnosis, Formulation, Personality

Individuals with high scores on the BSL-23 are more likely to have BPD and associated challenges with managing emotions, self-image, relationship issues, and general functioning in everyday life.

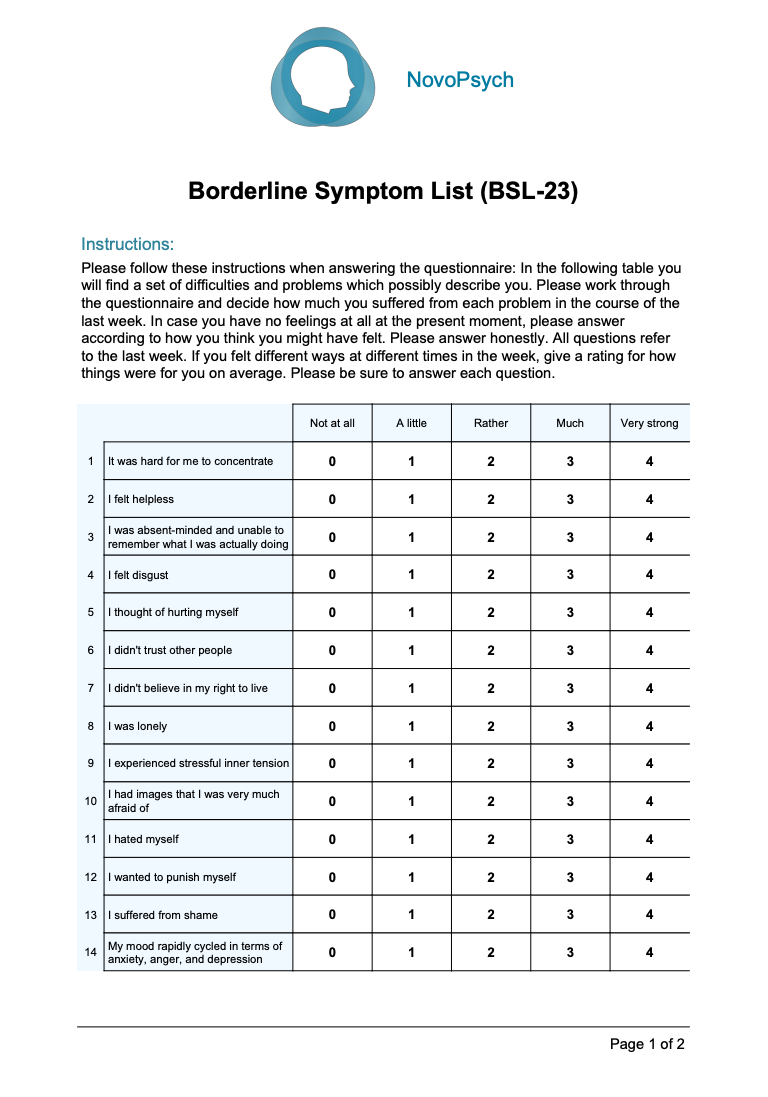

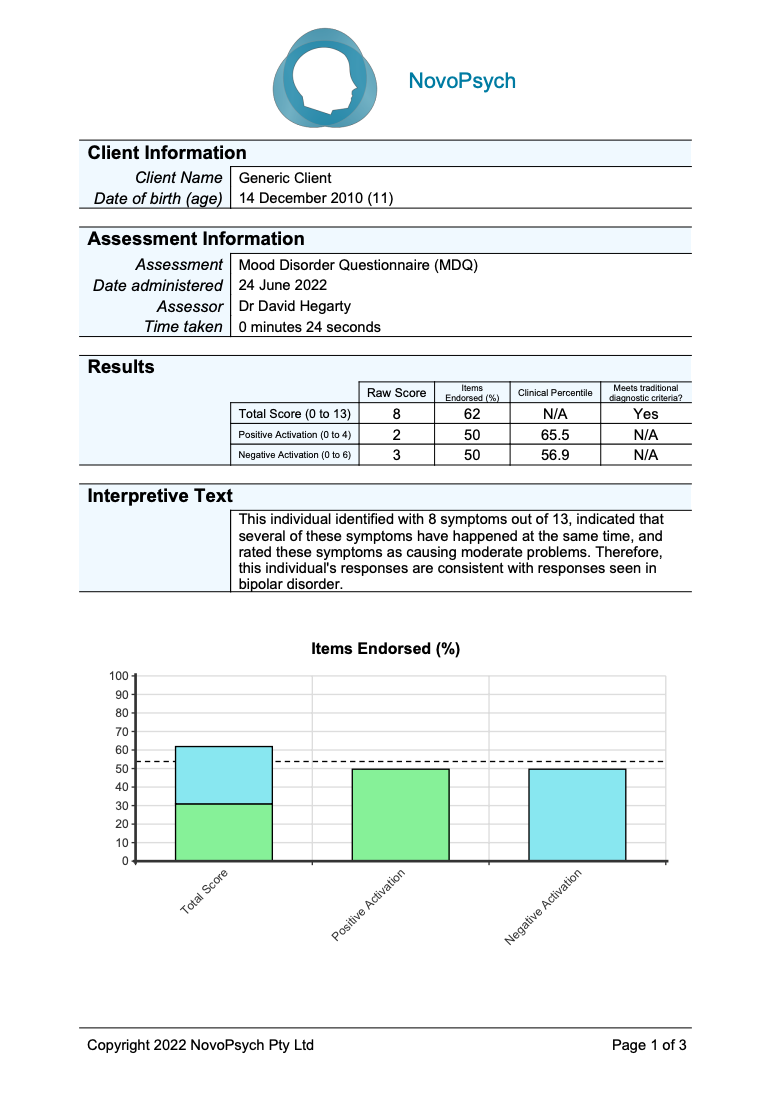

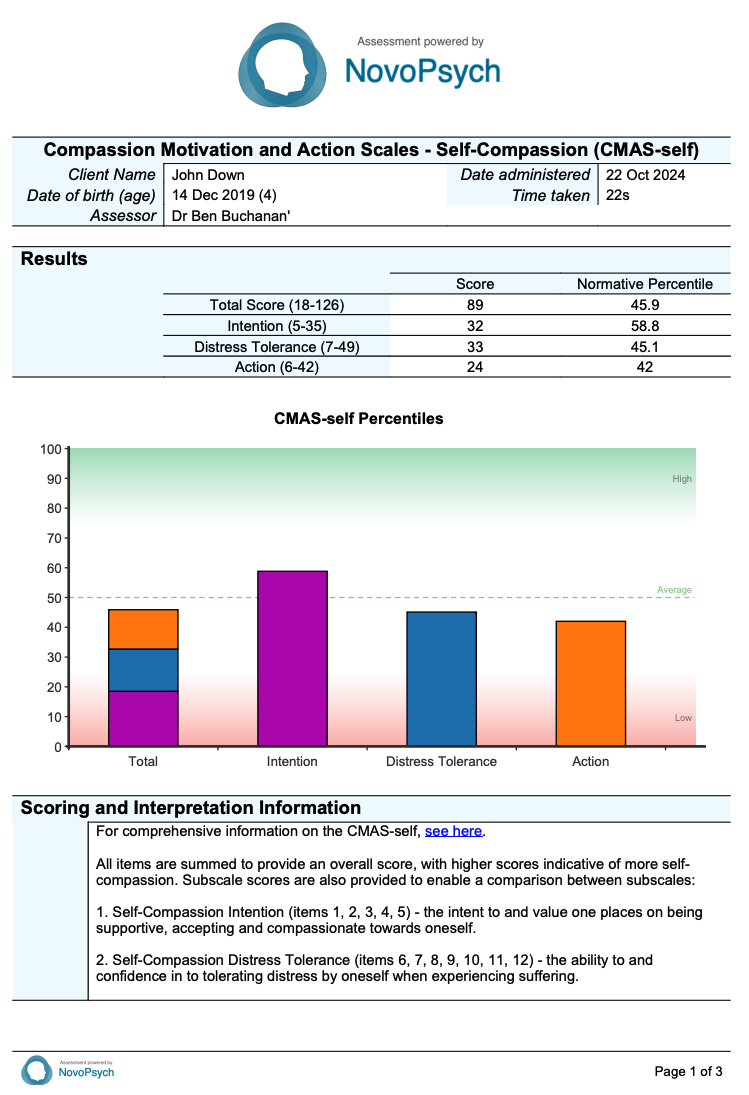

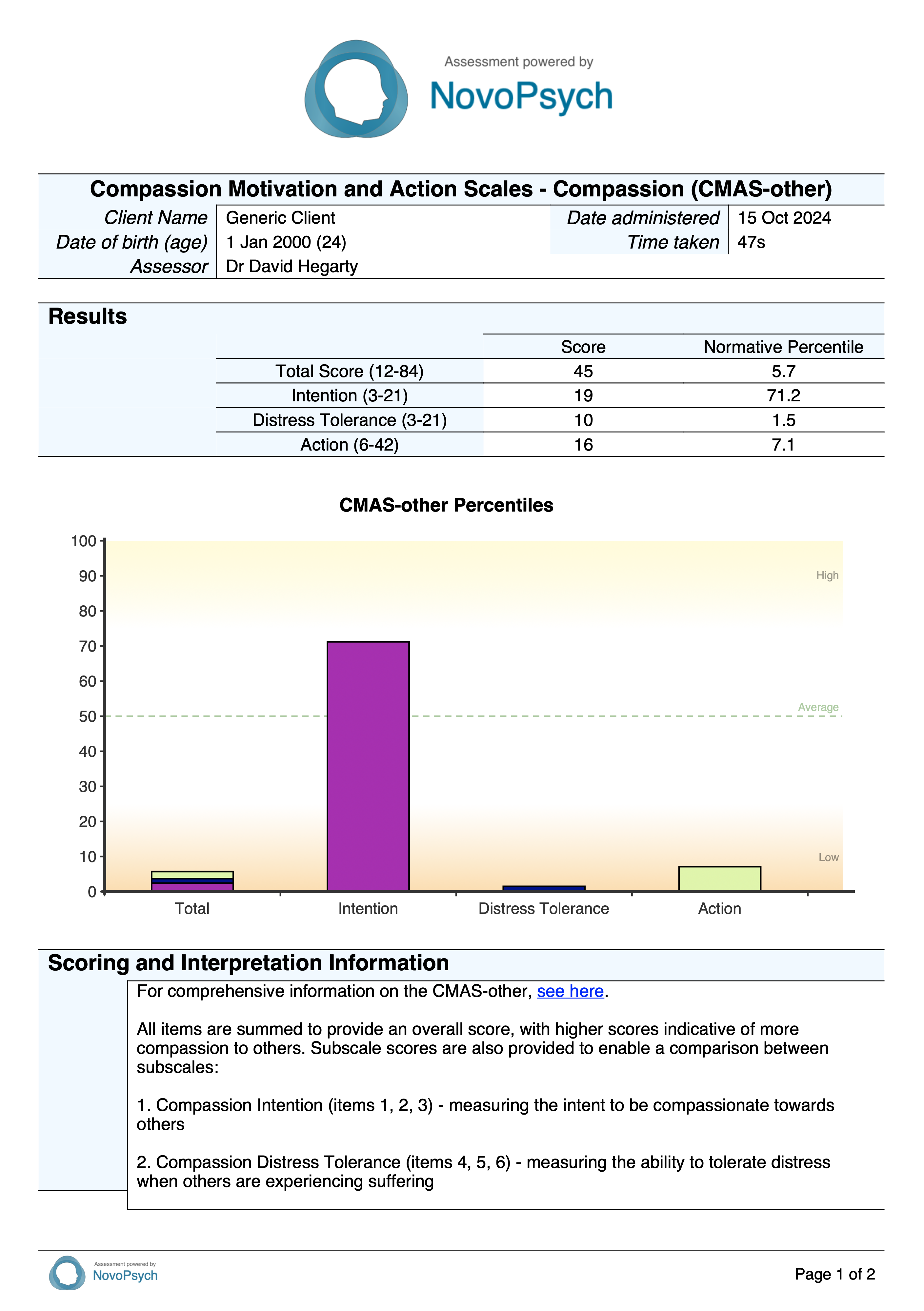

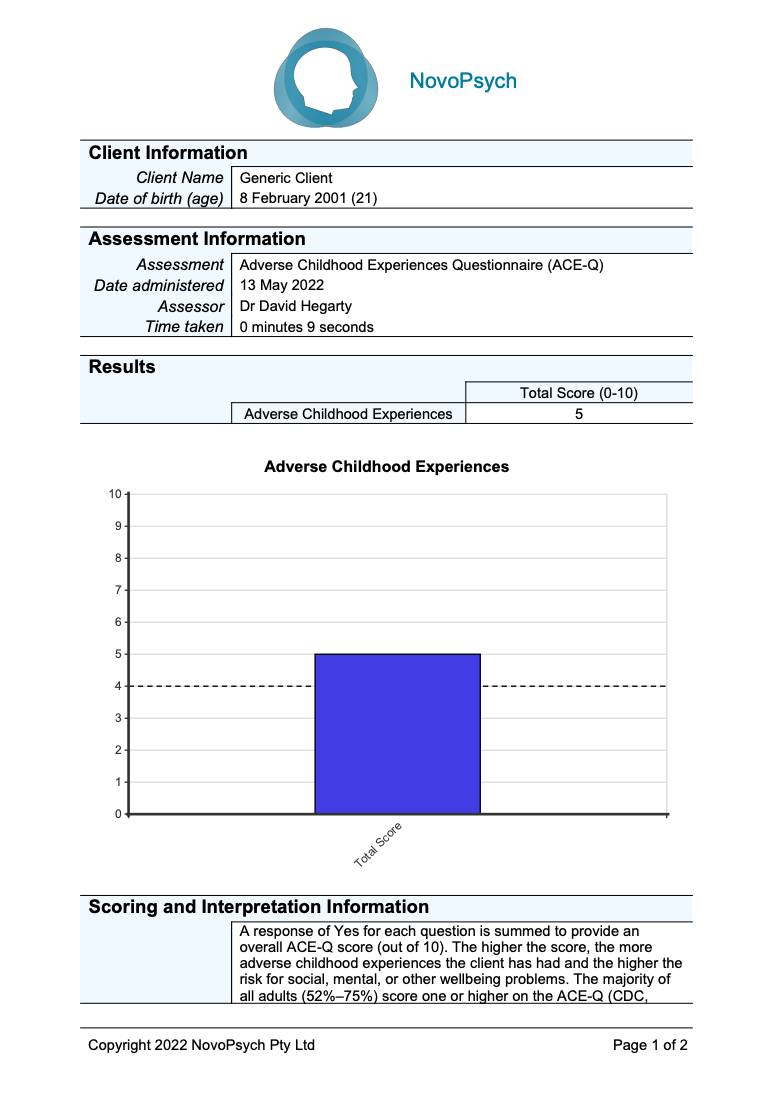

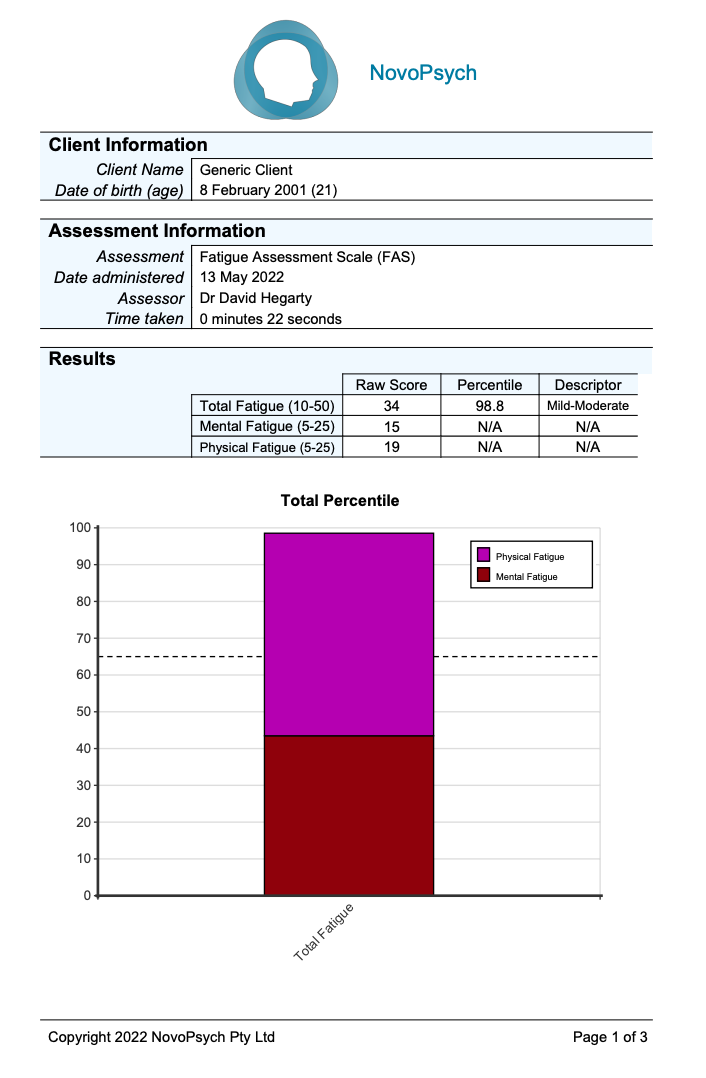

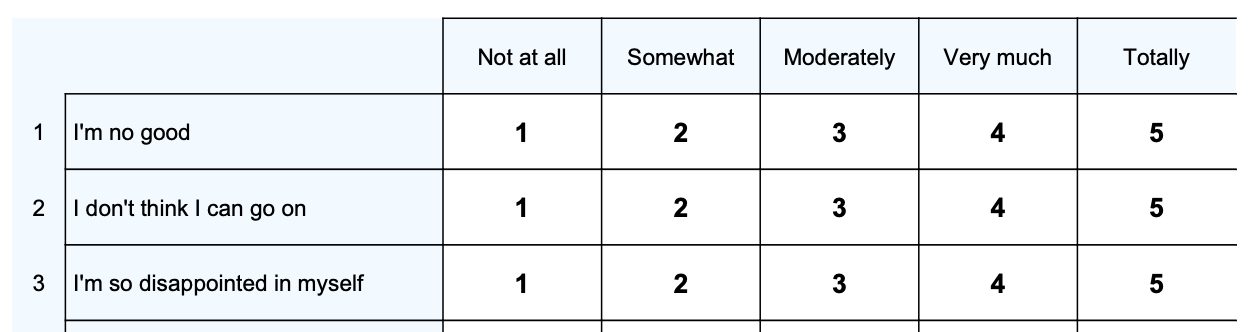

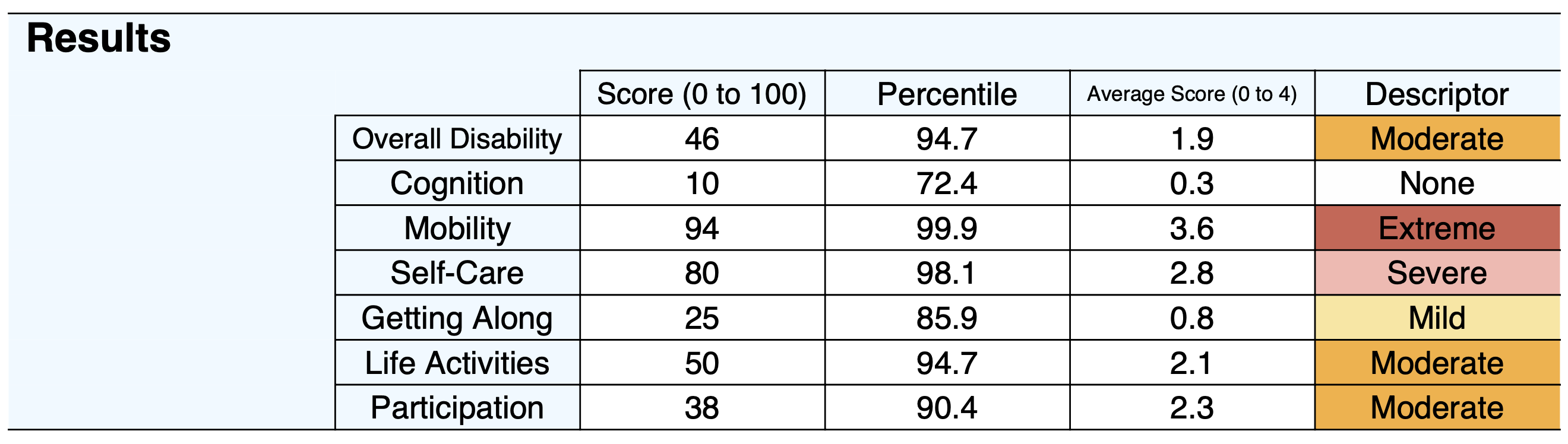

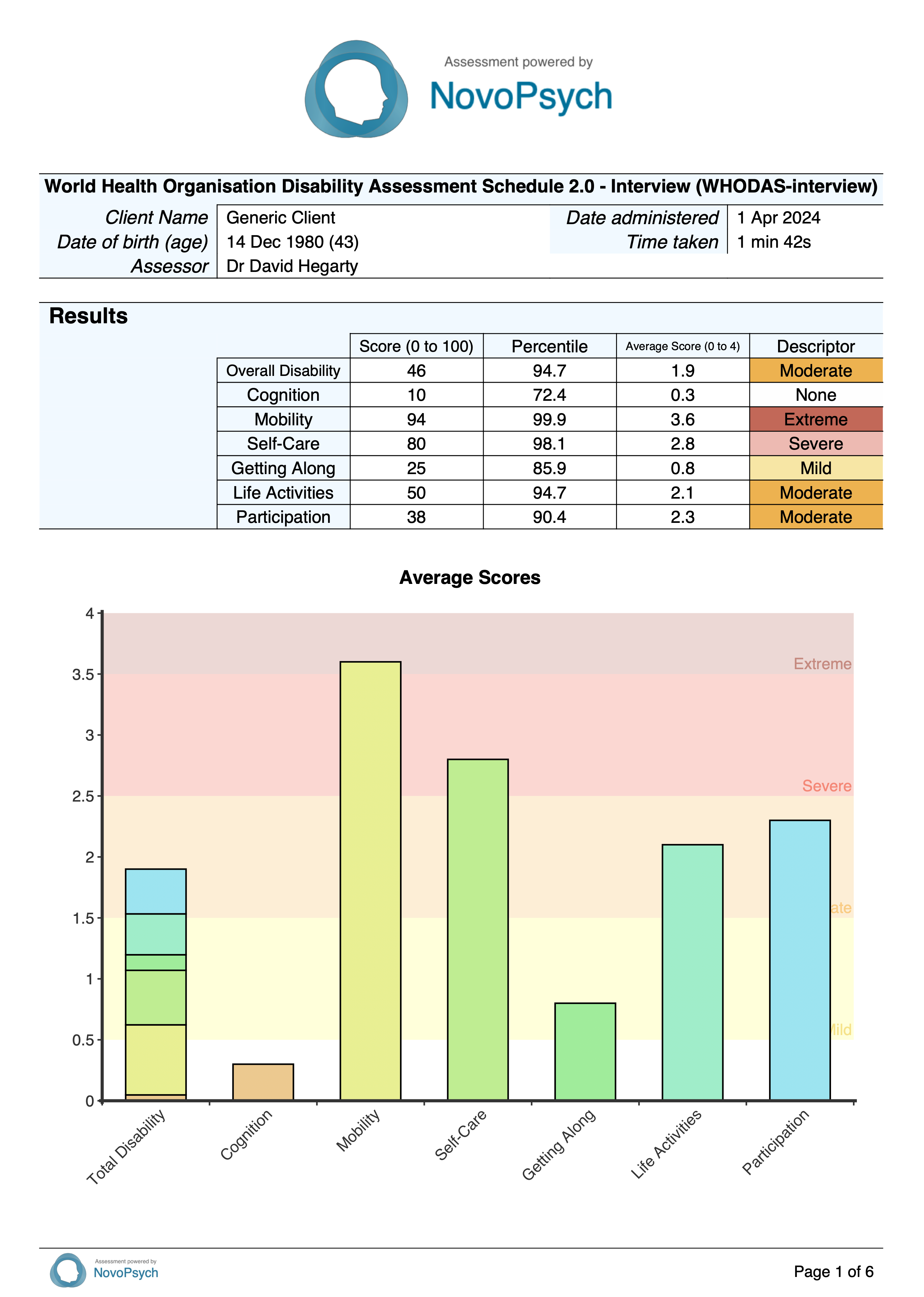

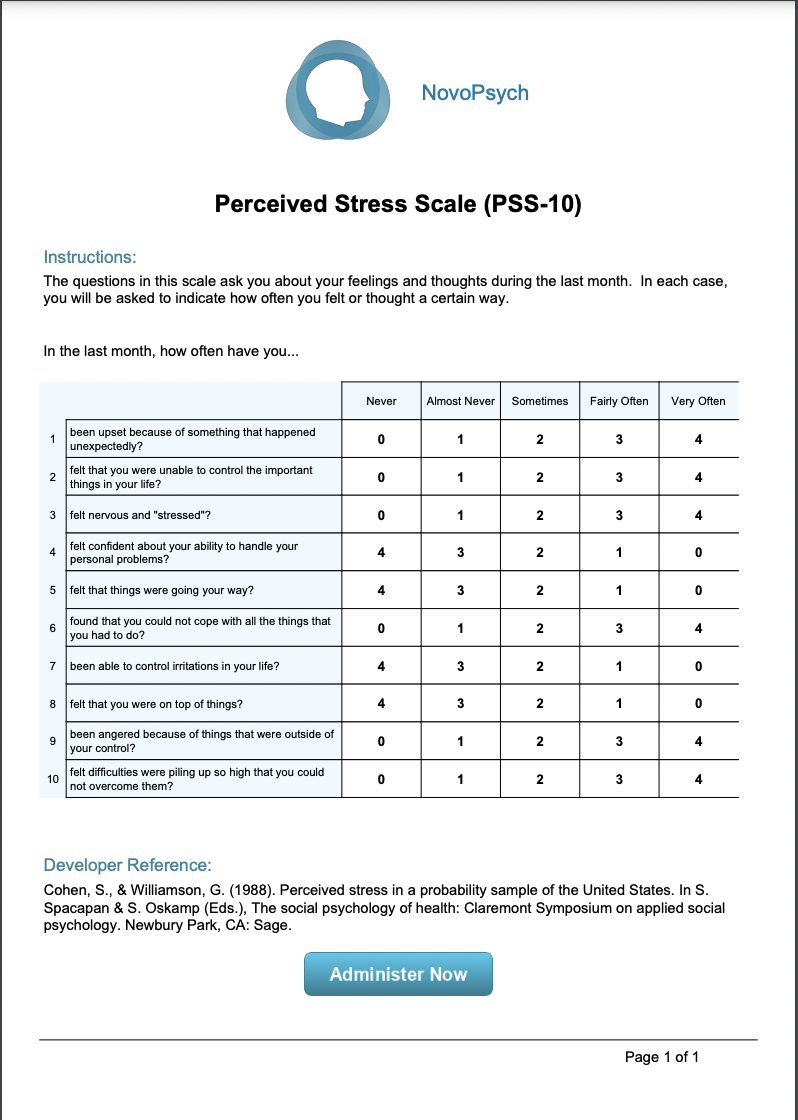

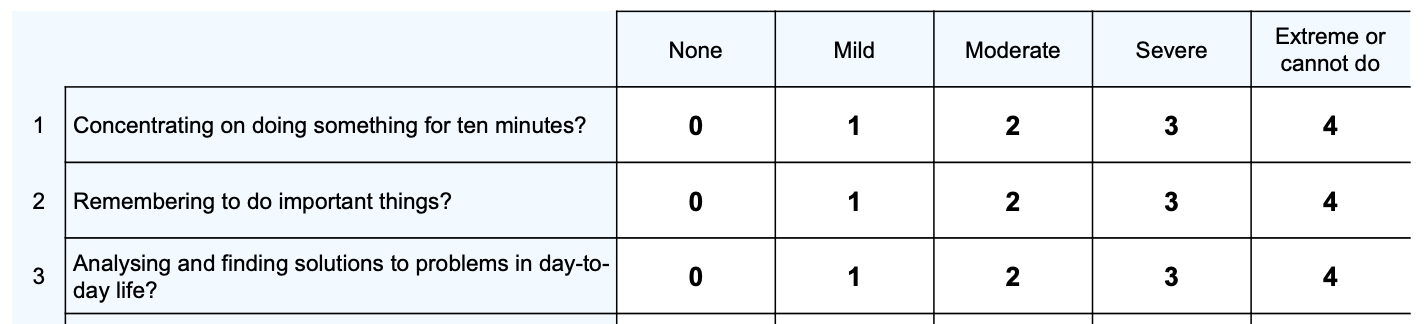

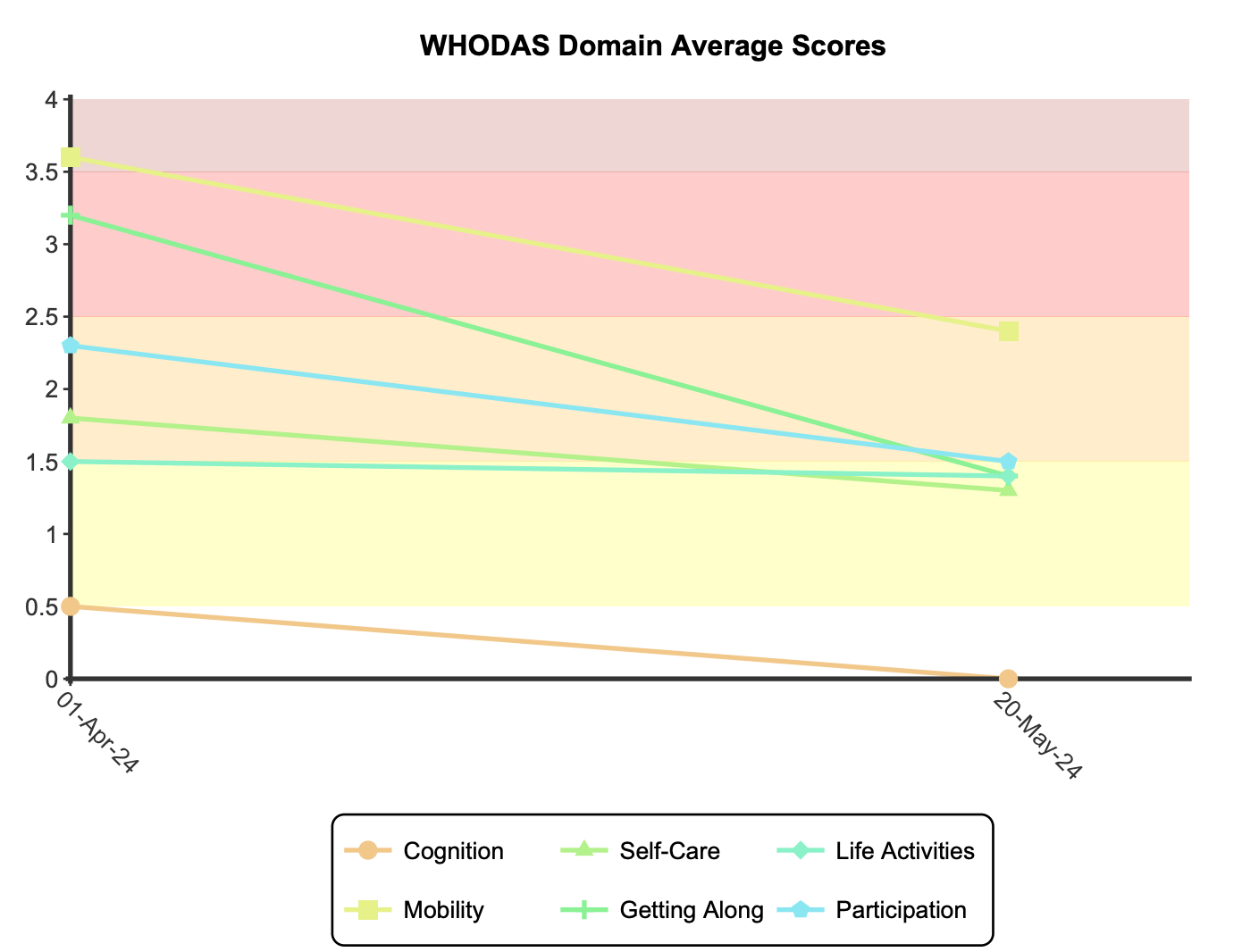

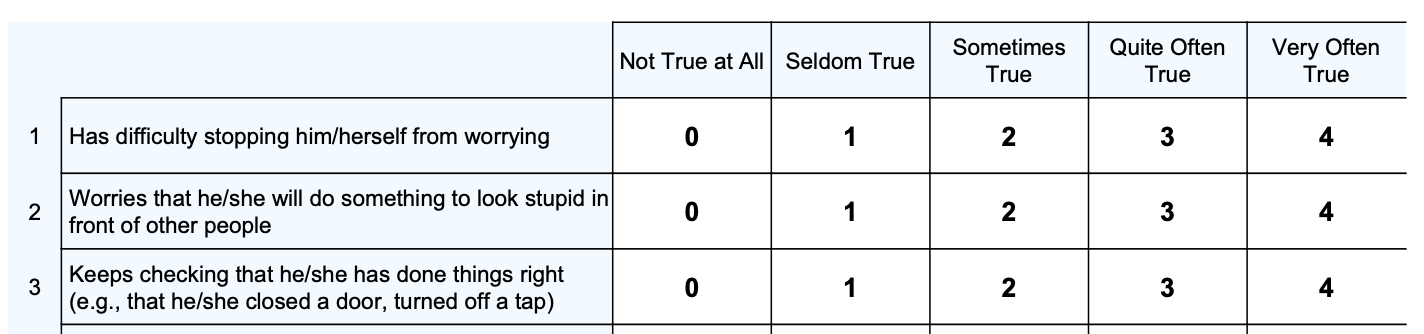

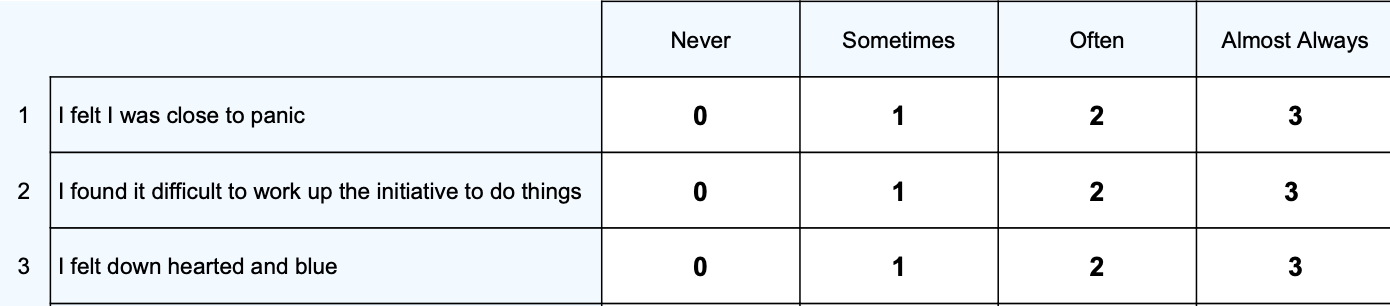

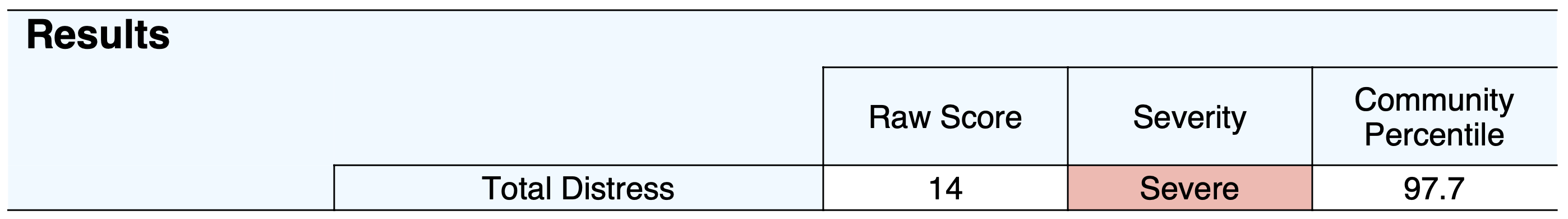

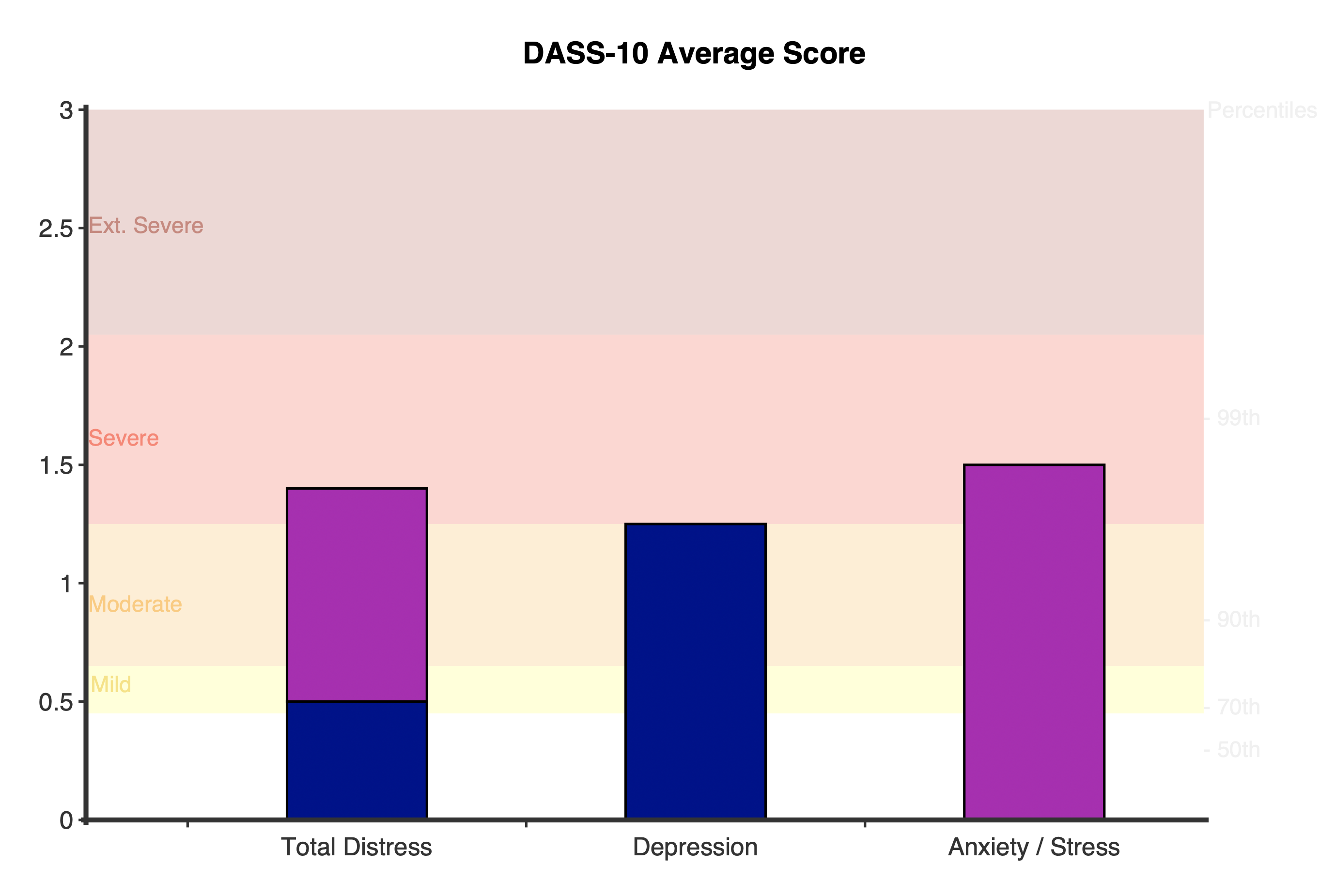

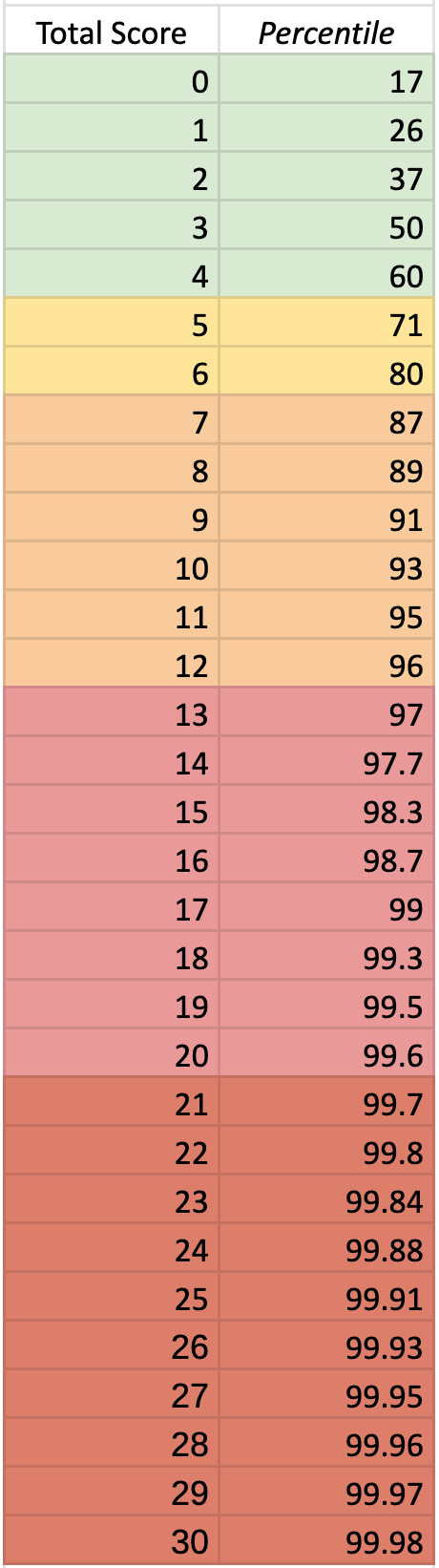

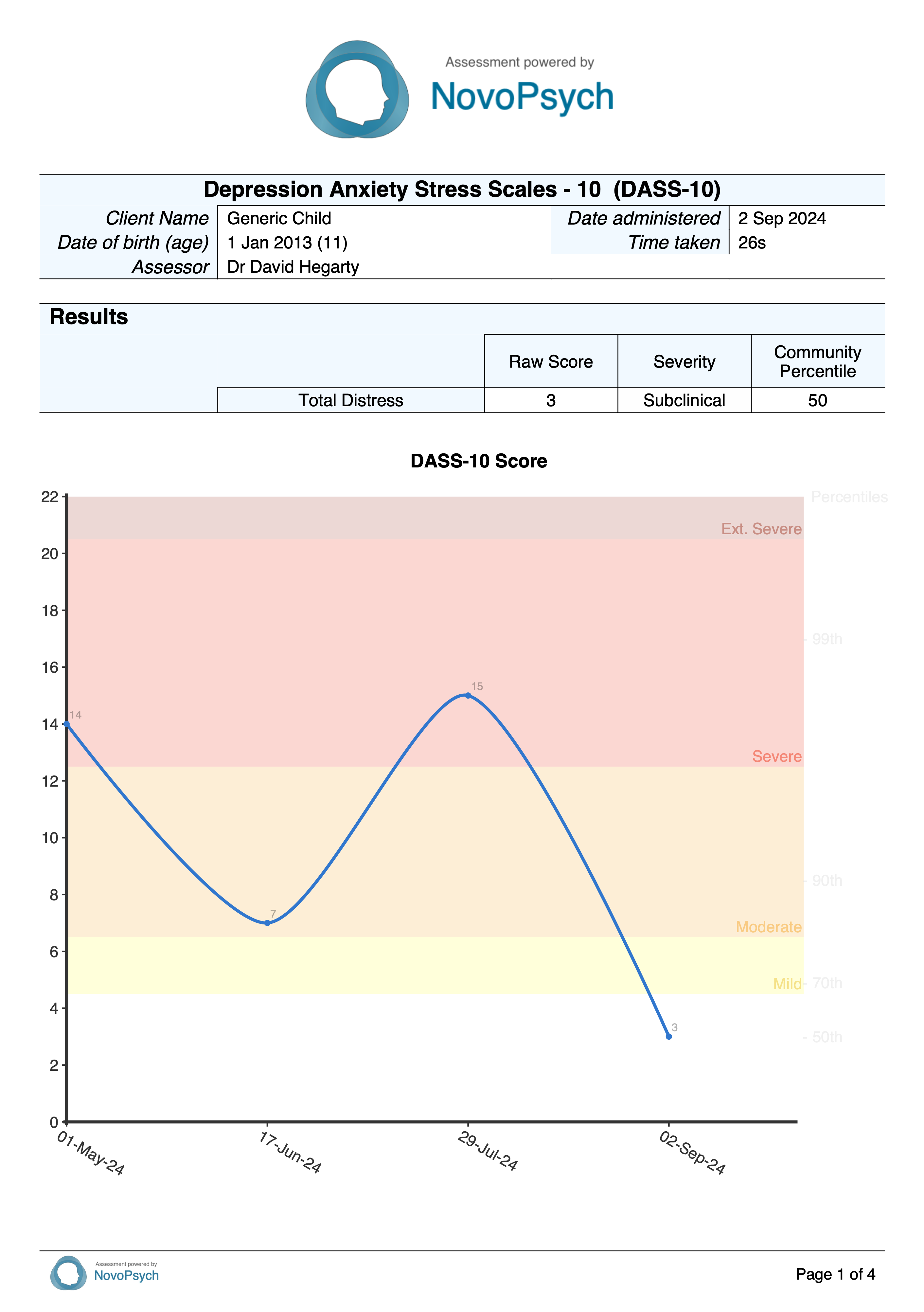

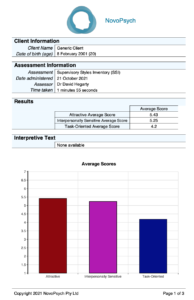

The average score of items (range 0 to 4, sum of scores divided by 23) is calculated, with a higher score indicating more impairment. Six grades of symptom severity were defined by Kleindienst et al. (2020) based upon the average score:

- None/Low: 0 – 0.3

- Mild: 0.3 – 1.1

- Moderate: 1.1 – 1.9

- High: 1.9 – 2.7

- Very High: 2.7 – 3.5

- Extremely High: 3.5 – 4

Scores of 1.50 or higher indicates the responses are consistent with BPD, with empirical data showing this cutoff score is able to discriminate between BPD patients and clients with other clinical psychopathology (e.g. anxiety disorders, major depressive disorders, schizophrenia, etc.; Kleindienst et al., 2020).

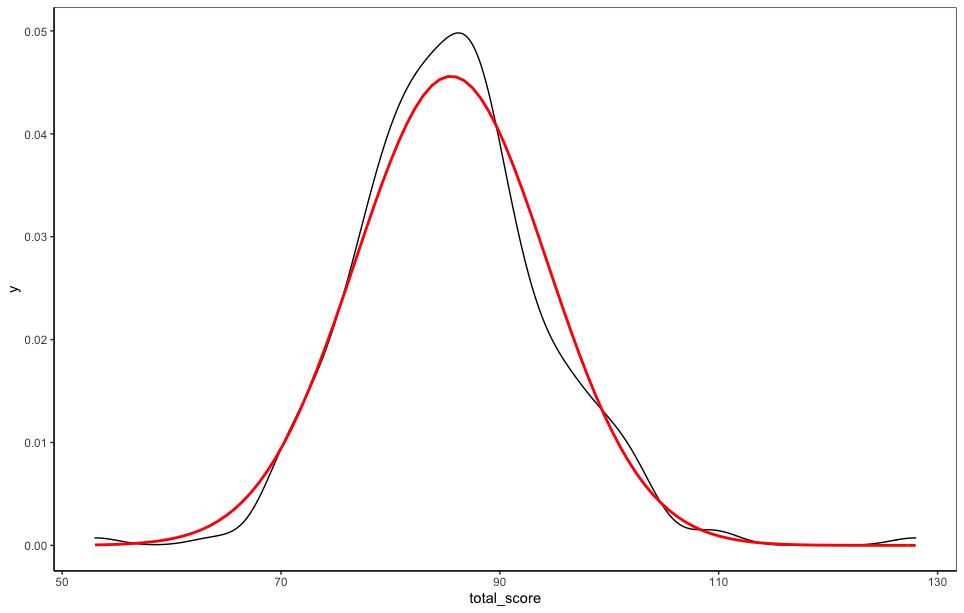

Percentiles are also presented comparing the respondents scores to a healthy group (n = 356; with no history of psychopathology) and a BPD group (n = 317; met DSM-V diagnostic criteria for BPD; Kleindienst et al. 2020). A percentile of 50 means that the client has scored at the typical level compared with the comparative group. An average score of 1.5 corresponds to a percentile of 17 compared to the BPD group, and a percentile of 99.9 compared to the healthy control group. These metrics indicate that a score of 1.5 is typical for someone with BPD but highly extreme compared to someone without a psychiatric diagnosis.

There is an additional question (24) that provides an indication of the client’s perspective on their overall well-being, but it is not included in the overall score. The rating on this last question (from 0 to 100) is strongly correlated with specific indicators of wellbeing for BPD patients, including self-perception, affect regulation, self-destruction, dysphoria, loneliness, intrusions, and hostility (Bohus, et al., 2007).

The BSL-23 items are based on criteria of the DSM-5, on the revised version of the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Personality Disorder, and on the experiences of both clinical experts and input from BPD (Kleindienst et al., 2020). The BSL-23 has a single factor structure and has excellent psychometric properties, with high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s of 0.97 and test-retest reliability of 0.82 within 1 week (Bohus, 2009). These properties have been replicated in several studies that validated the translations of the BSL-23 into 18 foreign languages (Kleindienst et al., 2020). The BSL-23 also has strong convergent validity with correlations between the BSL-23 and depression as measured by the BDI (r = 0.87), as well as general severity of psychopathology as measured by the SCL-90-R GSI (r = 0.89; Bohus, 2009).

Kleindienst et al. (2020) tested the BSL-23 on over 1,000 adults and developed cut-off scores and severity levels (none or low, mild, moderate, high, very high, and extremely high) for clients with BPD. They found that individuals with a severity grade of “none or low” were virtually free from diagnostic BPD-criteria and had a high level of global functioning corresponding to few or no symptoms. Severity grades indicating “high” to “extremely high” levels of BPD symptoms were observed at a much higher rate in treatment-seeking patients (70.0%) than in a healthy control group with no prior psychopathology history (0.0%)

Developer

Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R.-D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., Steil, R., Philipsen, A., & Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1159/000173701

References

Bohus, M., Limberger, M. F., Frank, U., Chapman, A. L., Kühler, T., & Stieglitz, R.-D. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL). Psychopathology, 40(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1159/000098493

Kleindienst, N., Jungkunz, M., & Bohus, M. (2020). A proposed severity classification of borderline symptoms using the borderline symptom list (BSL-23). Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00126-6