Dr Mandira Mishra

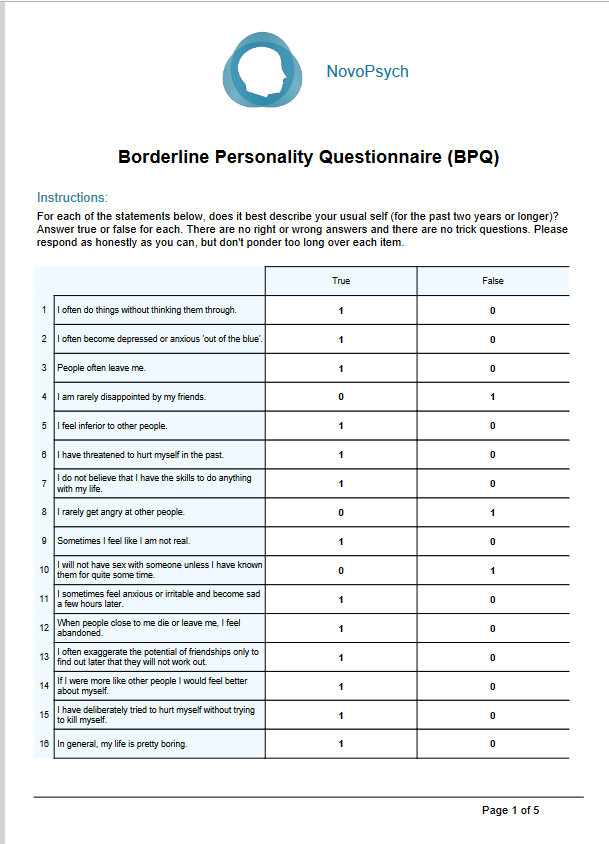

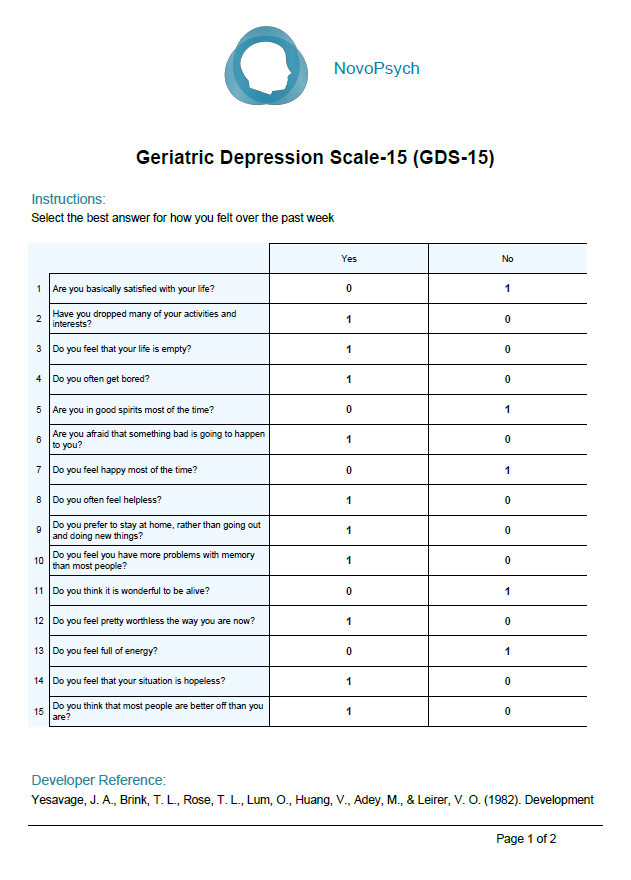

The Binge-Eating Scale (BES) is a 16-item self-report instrument designed to evaluate the presence and behavioural manifestations of binge-eating disorder (BED) (Gormally et al., 1982).

- 5 minutes

- Ages 18+

- Body Image & Eating

The scale assesses both the severity and frequency of binge-eating episodes, providing insights into the behaviours, emotions, and attitudes associated with BED, and aiding in the identification of individuals with disordered eating. The BES is a useful tool for clinicians to assess the severity and frequency of binge-eating behaviours. It provides a measure of both behaviours and associated feelings and cognitions.

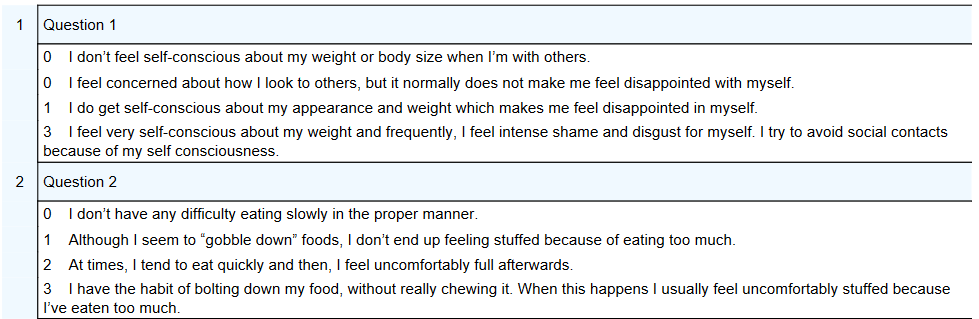

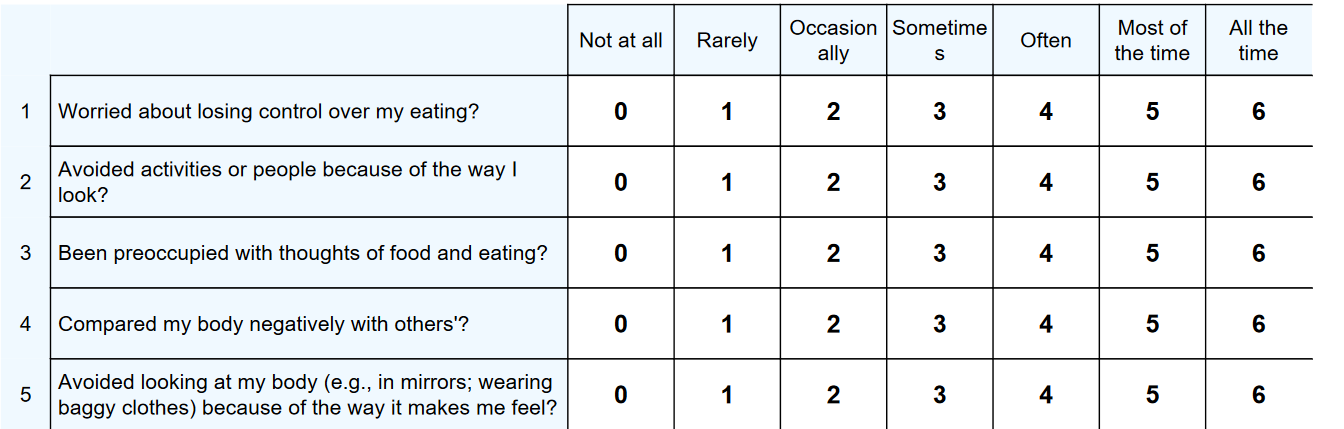

Example BES Items

The BES is adaptable for screening in clinical and non-clinical settings. It aids in screening, evaluating the progress of treatment over time, and assessing the overall responses to interventions.

Of the 16 items, 8 relate to the behavioural manifestations of binge-eating and 8 relate to feelings and cognitions in response to binge-eating, though the measure is uni-dimensional.

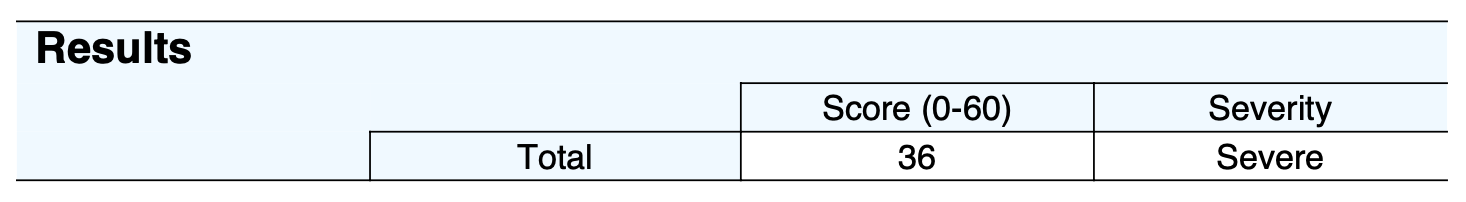

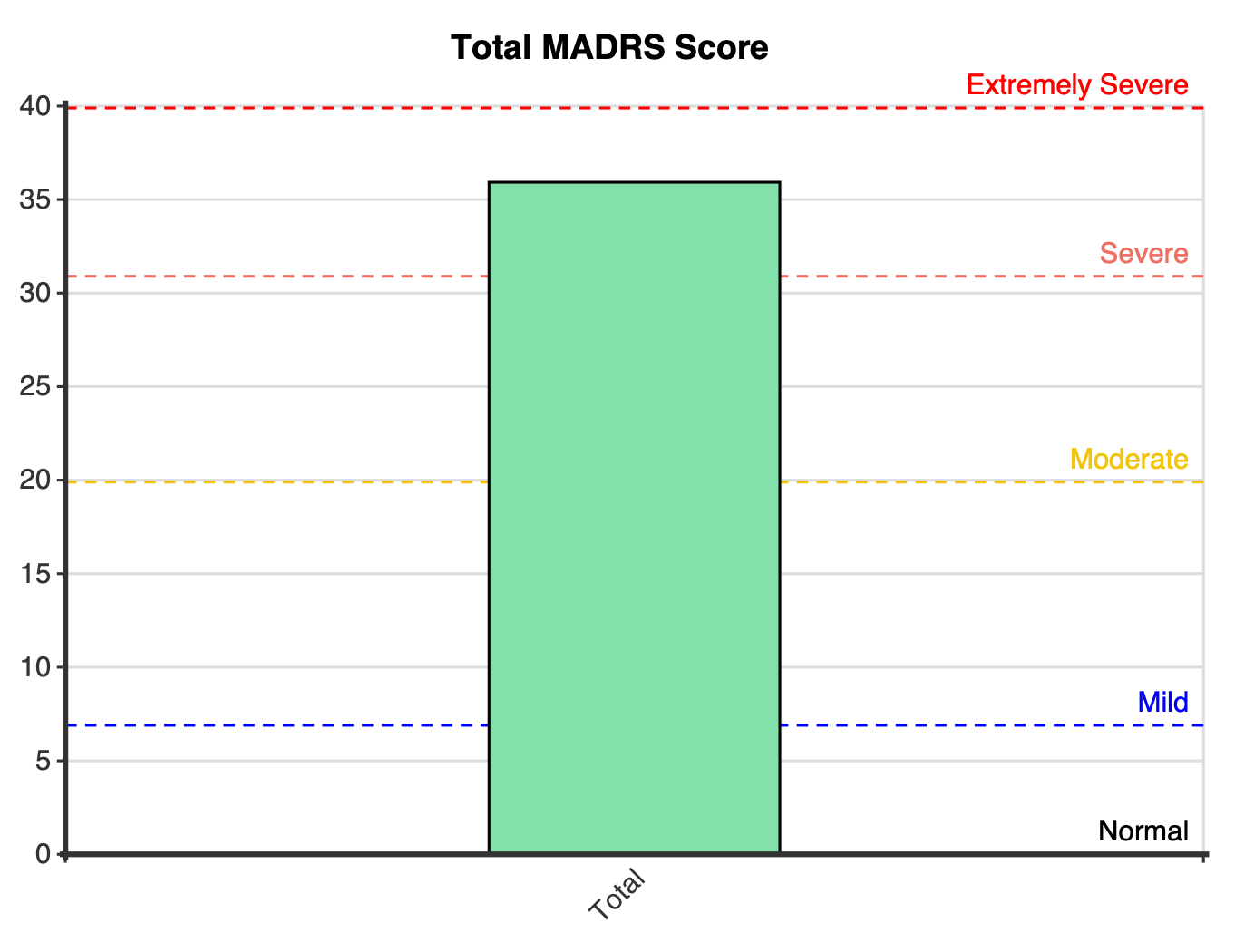

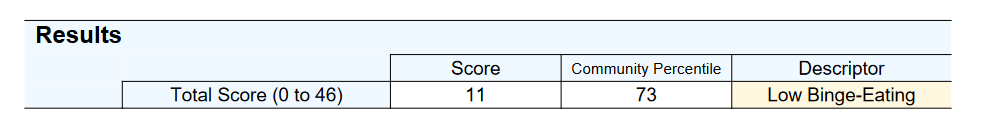

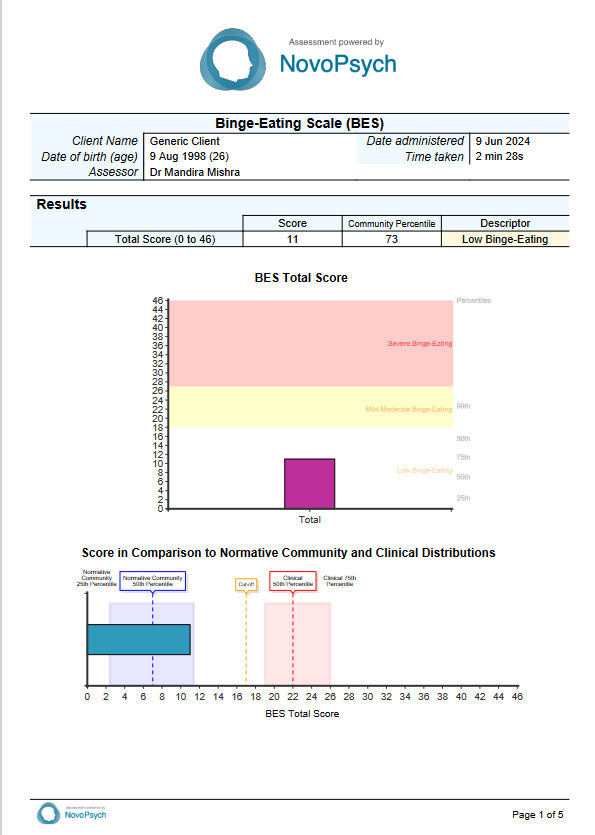

The total scores on the BES range from 0 to 46, with higher scores indicating a greater frequency and severity of binge-eating symptoms as outlined by the DSM criteria.

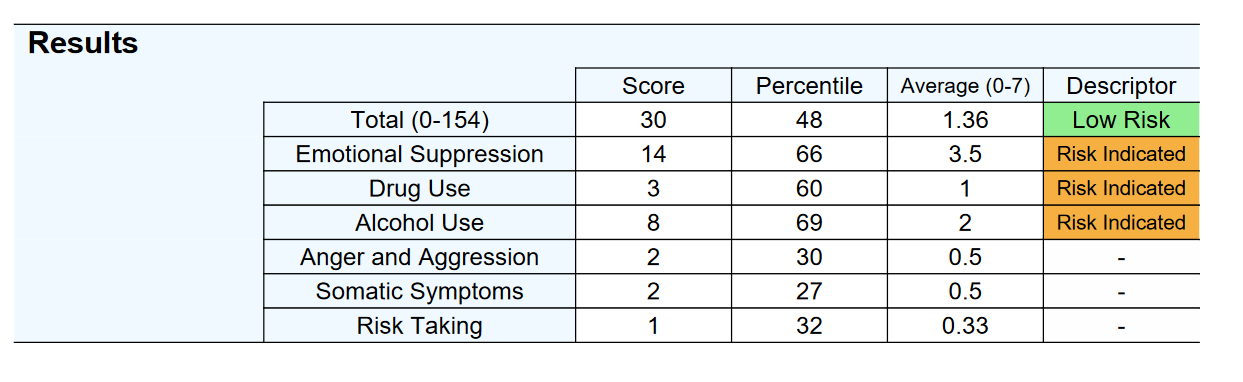

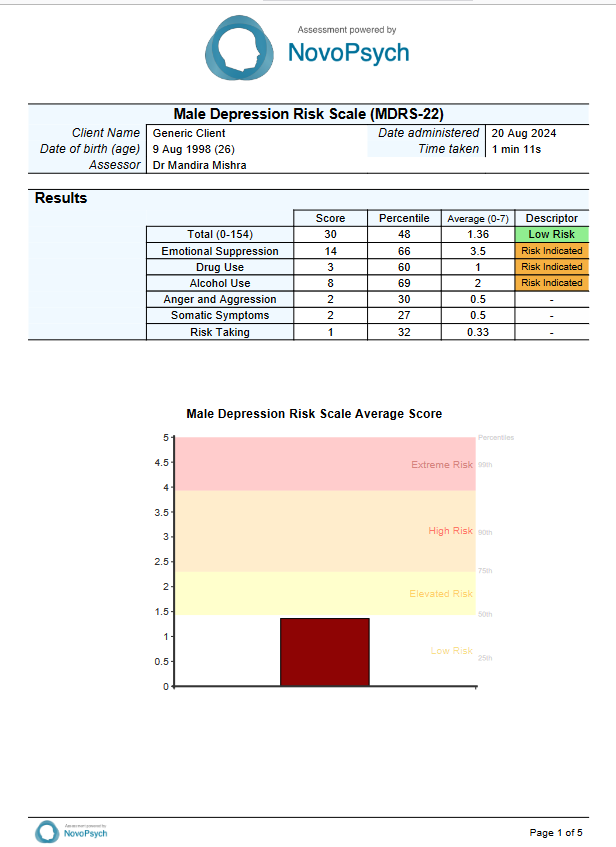

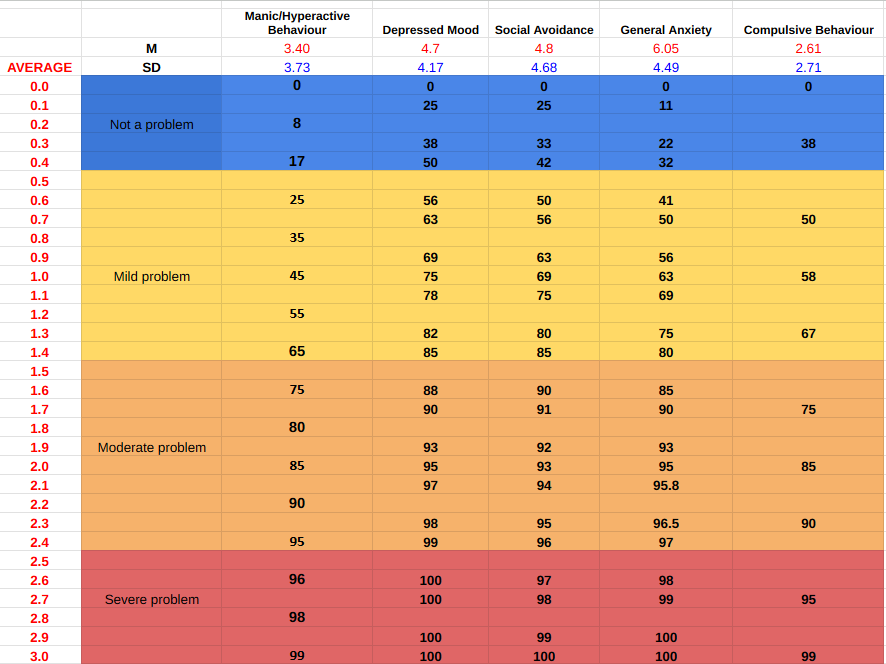

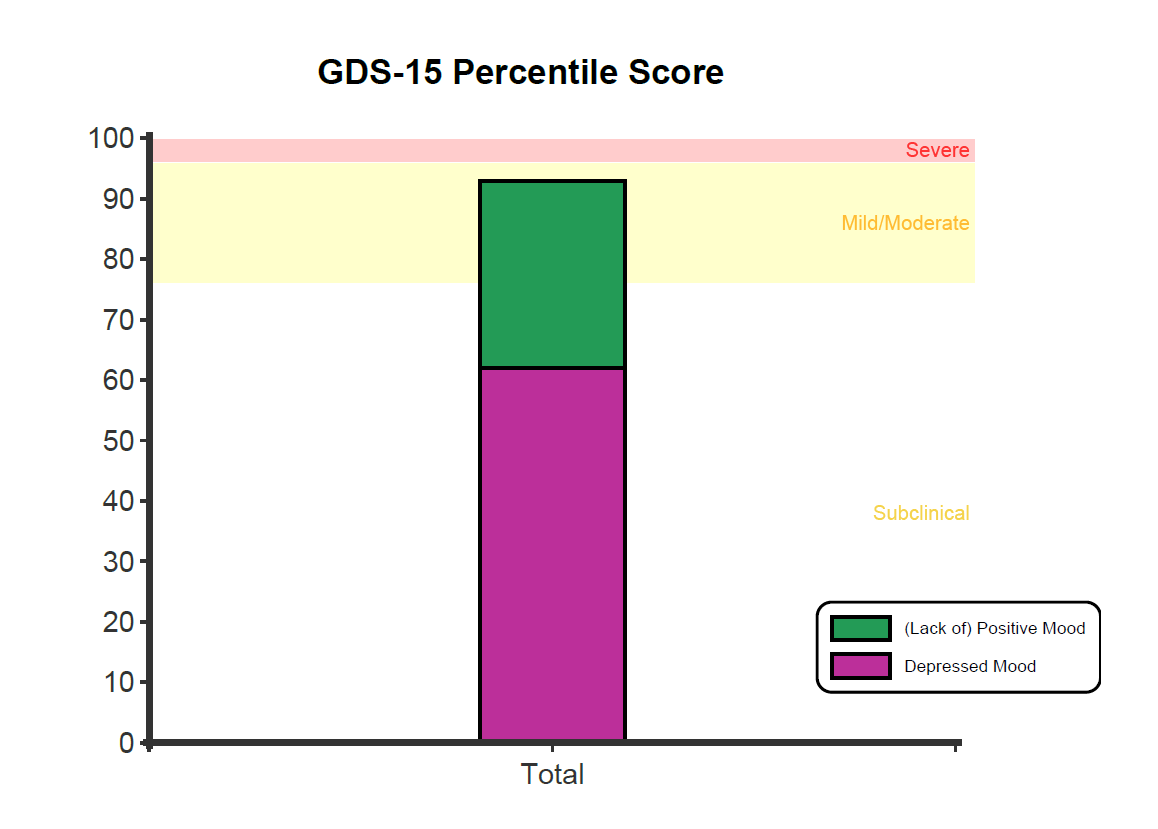

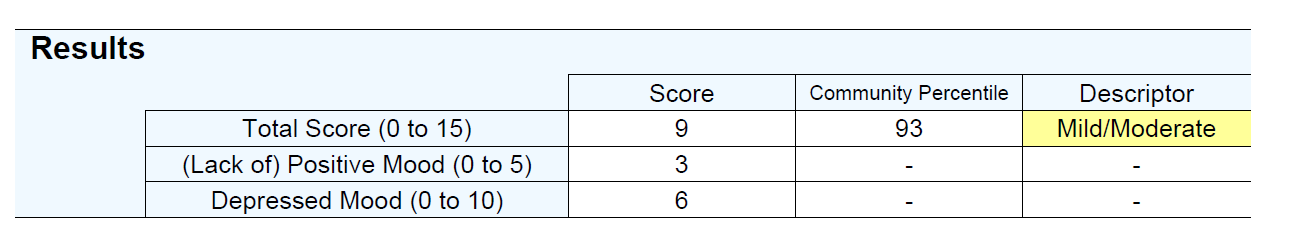

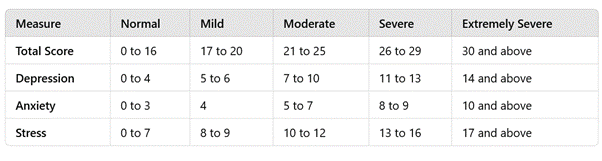

The scale classifies individuals into distinct severity categories based on their total scores, as follows:

- Low Binge-Eating: Scores of 17 or lower, which suggest minimal or no symptoms of binge-eating.

- Mild to Moderate Binge-Eating: Scores ranging from 18 to 26, reflecting a moderate level of binge-eating behaviour.

- Severe Binge-Eating: Scores of 27 or higher, indicating a high frequency and severity of binge-eating symptoms.

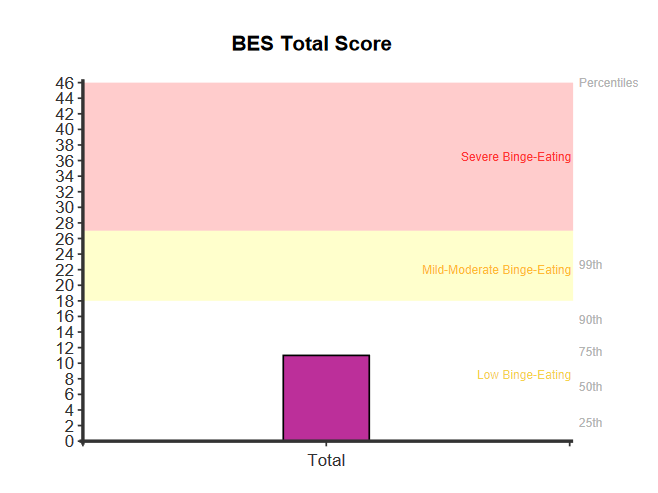

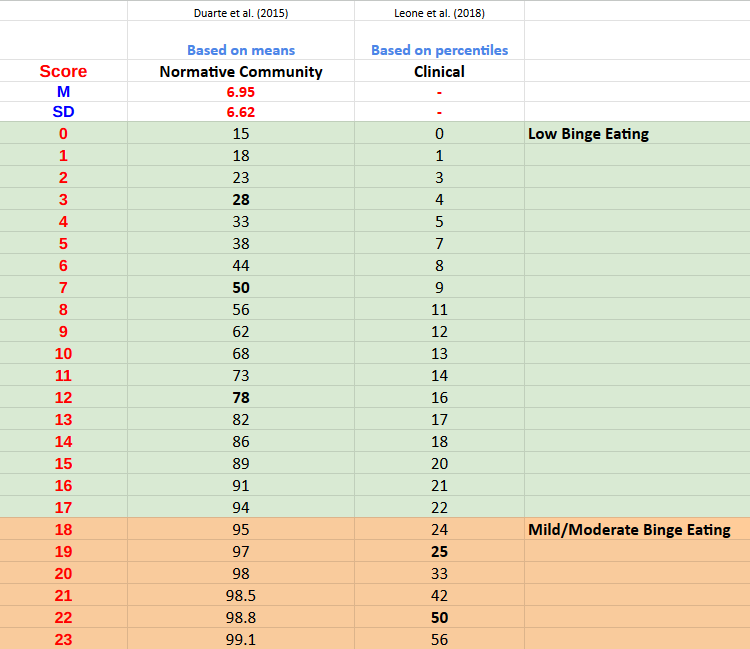

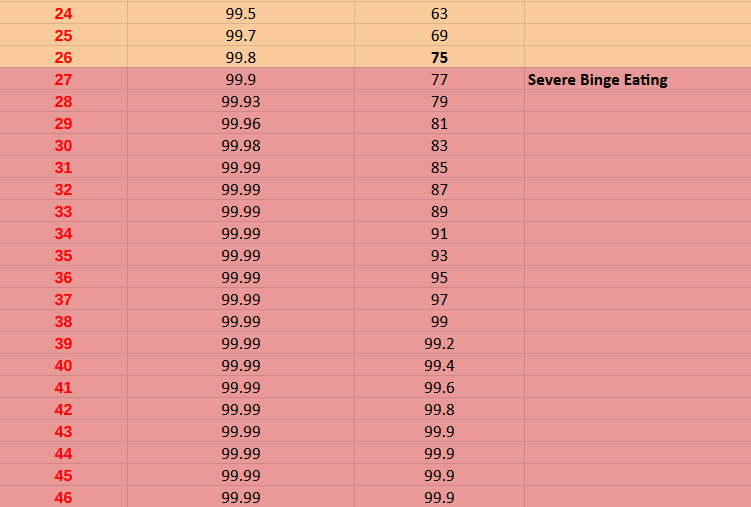

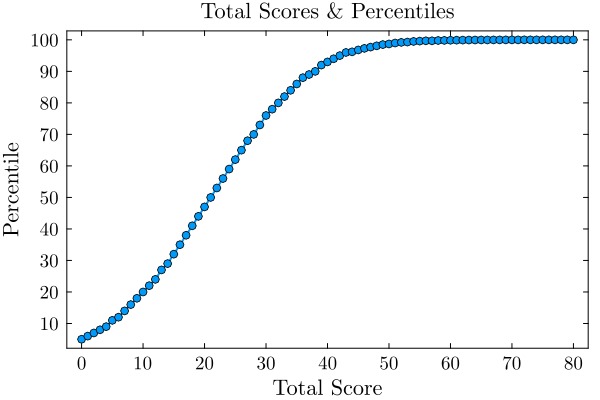

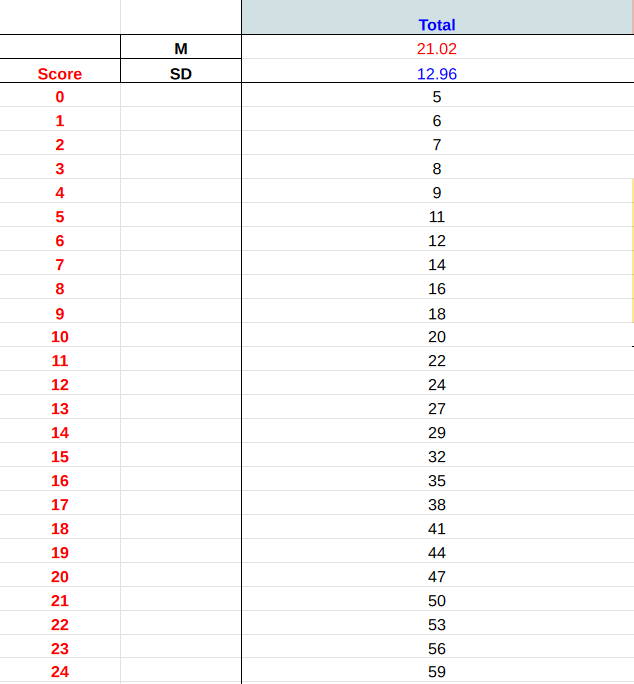

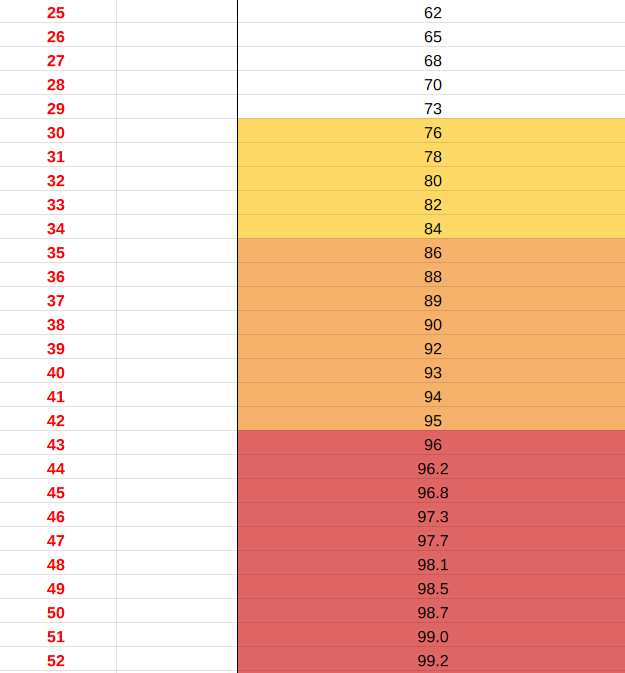

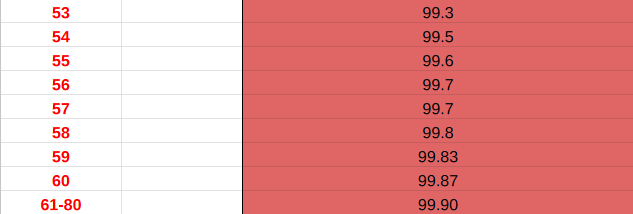

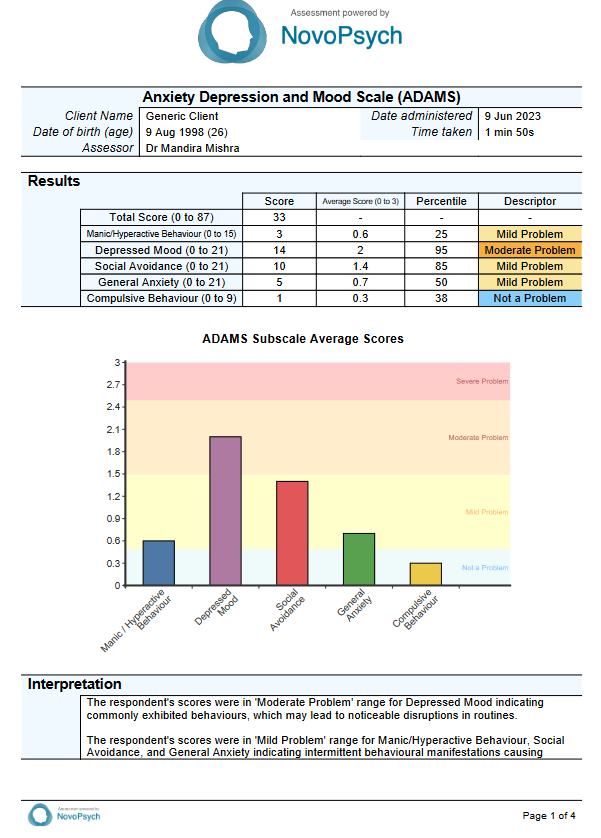

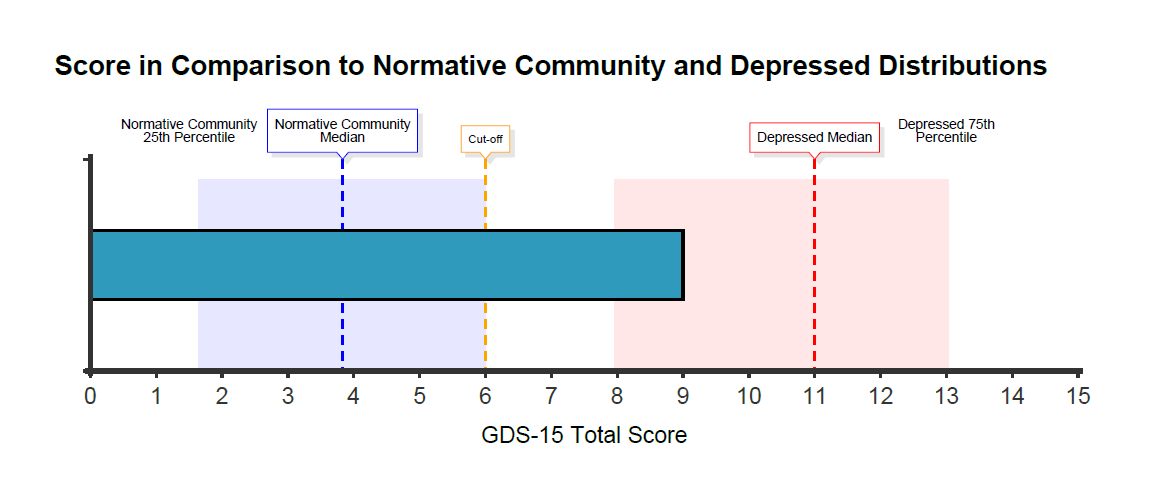

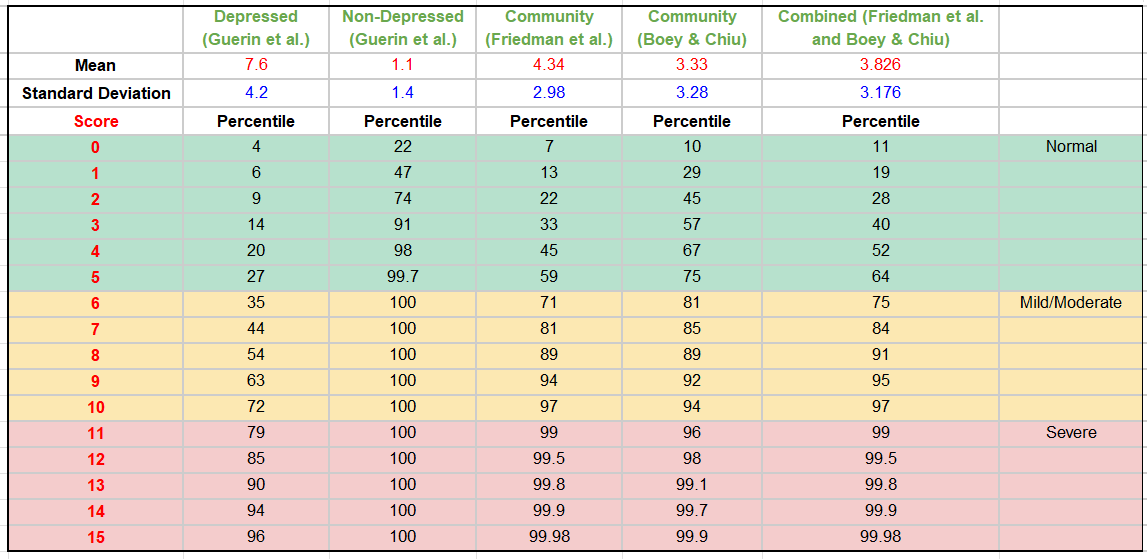

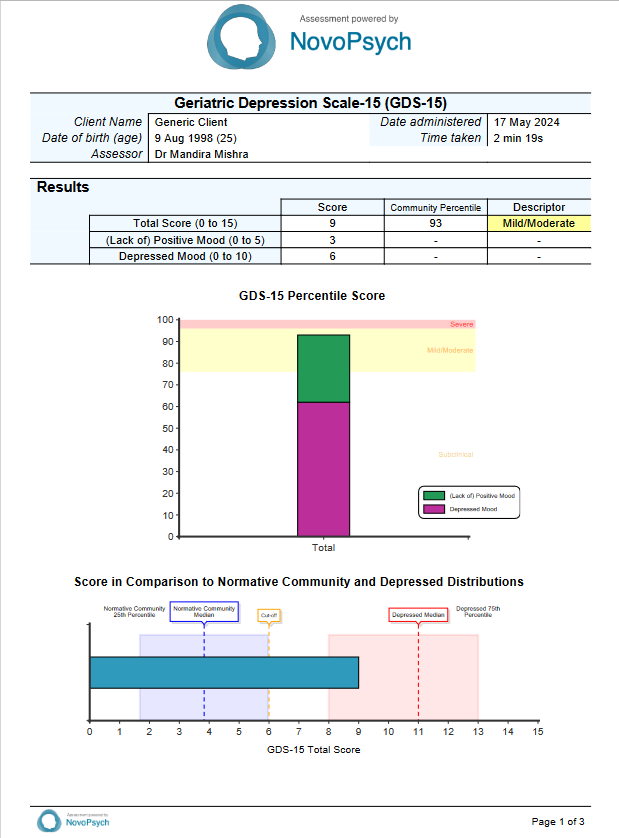

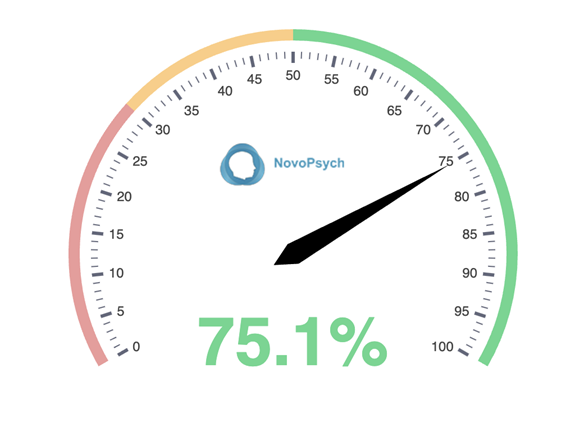

A percentile is used to contextualise a respondent’s score compared to the normative community sample. The normative community sample represents the typical level of binge eating symptoms found in the general population (Duarte et al., 2015). A percentile of 50 suggests a typical (and healthy) relationship with eating, whereas a percentile of 99 indicates that the respondent scores higher than 99 percent of individuals, indicating severe symptoms consistent with binge-eating disorder.

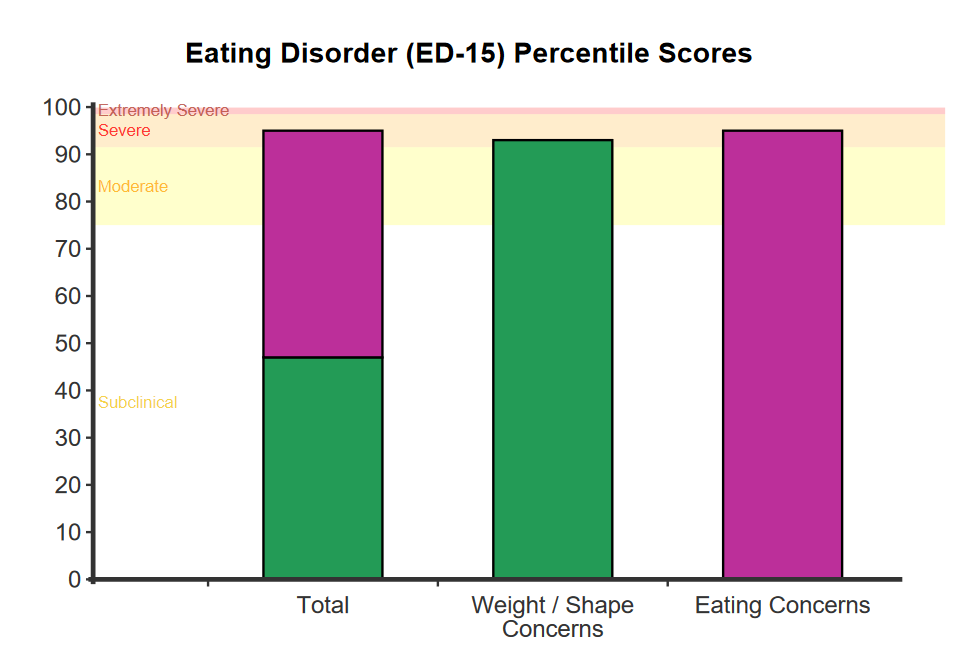

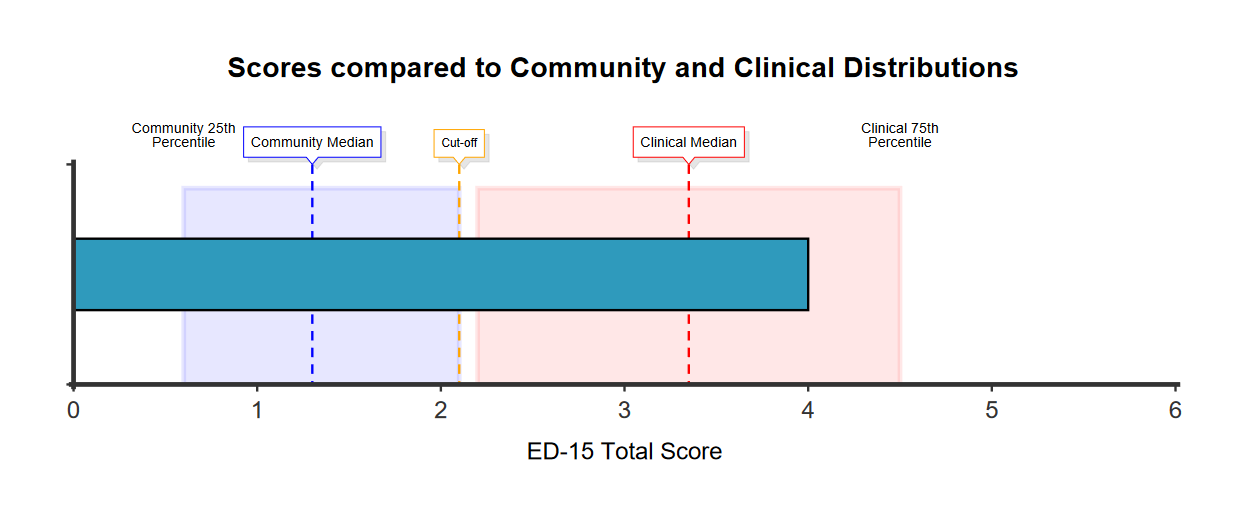

The horizontal graph presents the score in comparison to the normative community and clinical distributions, with shaded areas around the two middle quartiles (between the 25th and 75th percentile). The clinical distribution represents people diagnosed with binge-eating disorder (Leone et al., 2018). This graph helps contextualise scores in comparison to the distribution of responses among normative community and clinical samples (Duarte et al., 2015; Leone et al., 2018). Applying a cutoff score of 17, the BES accurately classifies 96.7% of cases, demonstrating a sensitivity of 81.8% and a specificity of 97.8% (Duarte et al., 2015).

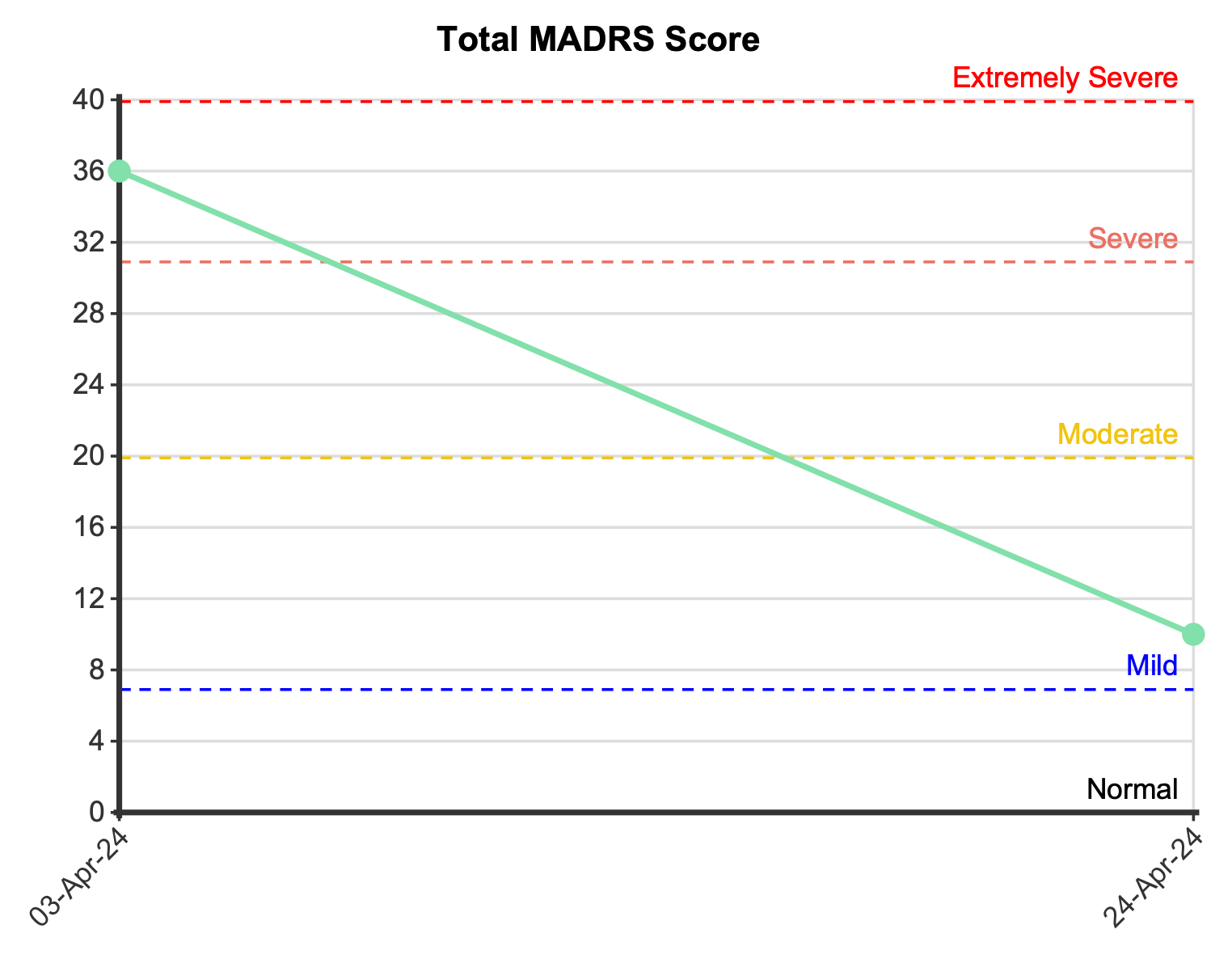

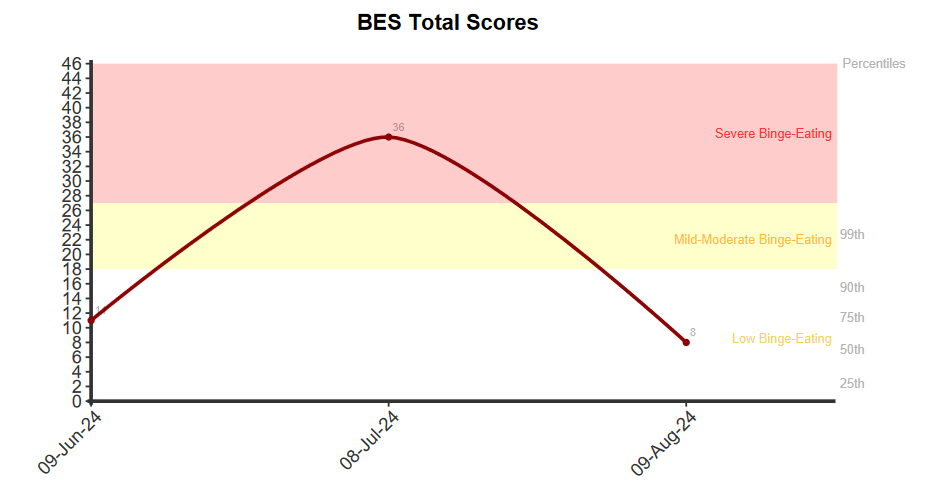

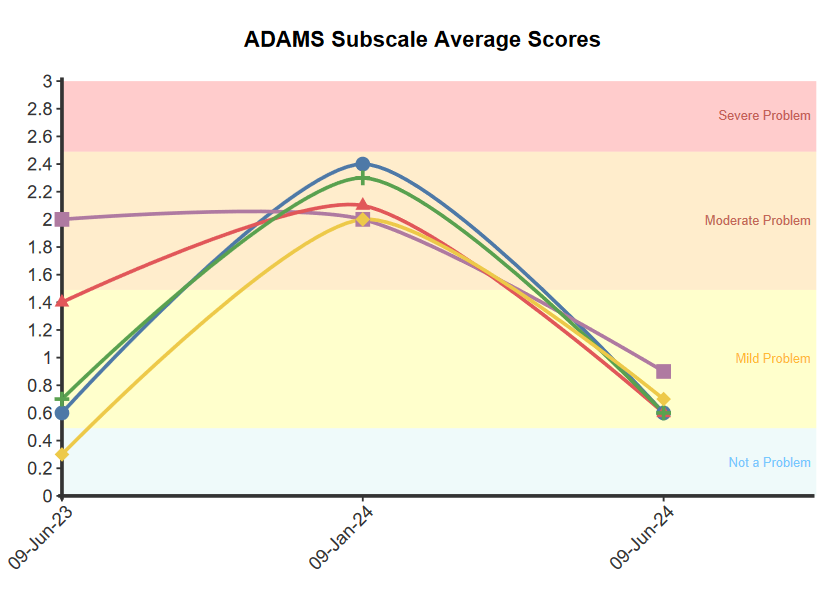

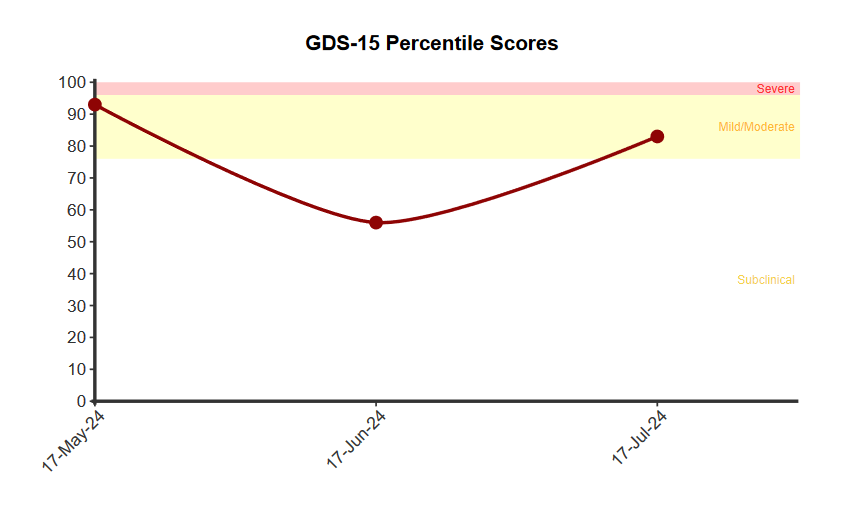

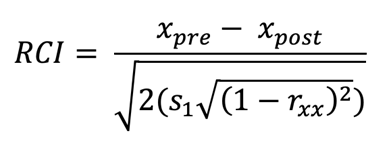

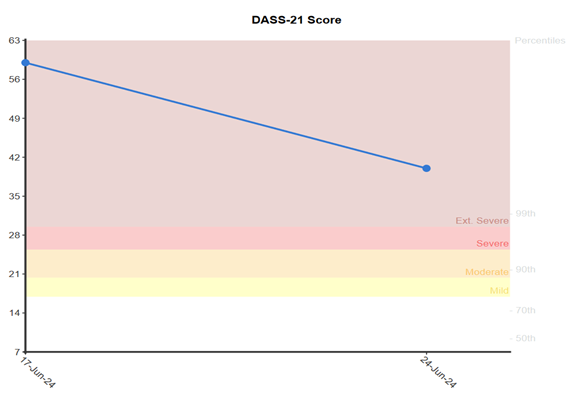

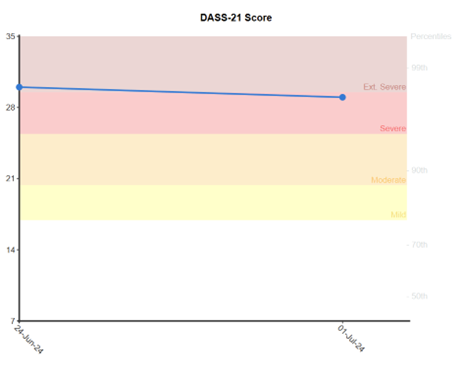

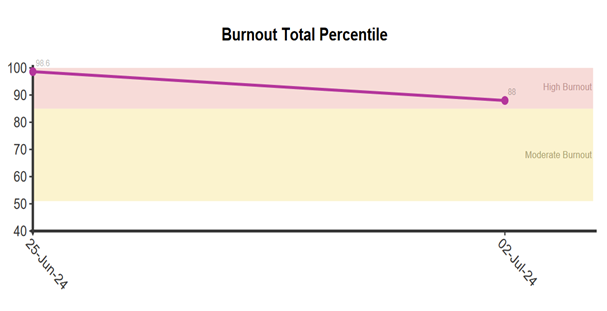

For multiple administrations, the line graph visually tracks the respondent’s total scores across sessions. A meaningful change (~ 0.5 SD) in score is defined as an increase or decrease of at least 4 or more points for the total score. This criterion is based on the Minimally Important Difference (MID) calculation. Such changes indicate meaningful improvement or reduction in symptoms, while a change of less than the specified points suggests no meaningful change in symptom severity between assessments.

Higher BES scores have shown a significant positive correlation with BMI, depression, negative mood, feelings of ineffectiveness, and low self-esteem. Conversely, lower BES scores are associated with health-related quality of life (Pasold et al., 2013). Individuals with BED have higher lifetime rates of major depression, as well as a greater likelihood of having other mood, substance use, and personality disorders, compared to those without BED (Telch & Stice, 1998).

The BES was developed using two samples of overweight individuals seeking behavioural obesity treatment. The first sample (N = 65) was exclusively female, with a mean age of 39.3 years (SD = 8.1, range 24 to 55). The second sample (N = 47), which included 68% females, had a mean age of 41.2 years (SD = 11.6, range 24 to 67). For these samples, the pooled BES scores had a mean of 21.03 (SD = 8.75). The development of the BES involved several steps. First, characteristics of binge-eating were identified based on clinical observations and the DSM criteria, leading to 16 items divided into feelings/cognitions and behavioural manifestations. Statements reflecting various severities for each characteristic were weighted by the authors, with final weights assigned through discussion.

To compare the BES to an external criterion, structured interviews assessing binge-eating severity through frequency, food amount, and emotional impact were conducted. Interviewers, trained and tested for reliability, used this criterion to ensure accurate ratings, which were generally consistent (Gormally et al., 1982).

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) conducted on a community sample of 1008 women (Mean age = 39.48, SD = 10.05) confirmed the BES’s one-dimensional structure with excellent fit to the data (Duarte et al., 2015). The internal consistency analysis of the BES showed that respondents endorsing higher-weighted statements generally had higher total scores (Gormally et al., 1982). The scale demonstrated very good construct reliability with a Composite Reliability (CR) of .96 and good convergent validity with an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of .61 (Duarte et al., 2015).

The BES has high positive correlations with the EDE-Q total score, particularly with the shape and weight concern subscales, and a moderate correlation with the restraint subscale. Additionally, the scale shows a strong positive correlation with emotional eating and with depression, stress, and anxiety as measured by the DASS-21. A moderate positive correlation was found between the BES and Body Mass Index (BMI) (Duarte et al., 2015). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the scale, when repeated one month after the initial test, was 0.83 (p < 0.01), indicating strong stability and reliability (Yan et al., 2023).

A sample of 1507 individuals diagnosed with binge-eating disorder and with a median age of 46 (range 18 to 70, 72.2% women), was used to determine clinical percentiles (Leone et al., 2018). The sample used to compute normative community percentiles consisted of 1,008 female participants ranging in age from 18 to 60 years, with a mean age of 29.21 years (SD = 11.63). This included 553 college students and 455 individuals from the general population (Duarte et al., 2015).

Individuals are categorised into three severity groups based on established cut scores by Marcus et al., (1985):

- Low Binge-Eating (score ≤ 17, percentiles between 15 and 94),

- Mild to Moderate Binge-Eating (score 18–26, percentiles between 95 and 99.8), and

- Severe Binge-Eating (score ≥ 27, percentiles over 99.8) (Duarte et al., 2015).

These classifications are based on the framework established by Marcus et al. (1985), providing a structured approach to evaluating the intensity of binge-eating behaviour. The BES effectively differentiates between individuals having low, mild to moderate, or severe binge-eating problems (Gormally et al., 1982; Marcus et al., 1985).

Supplementary Material

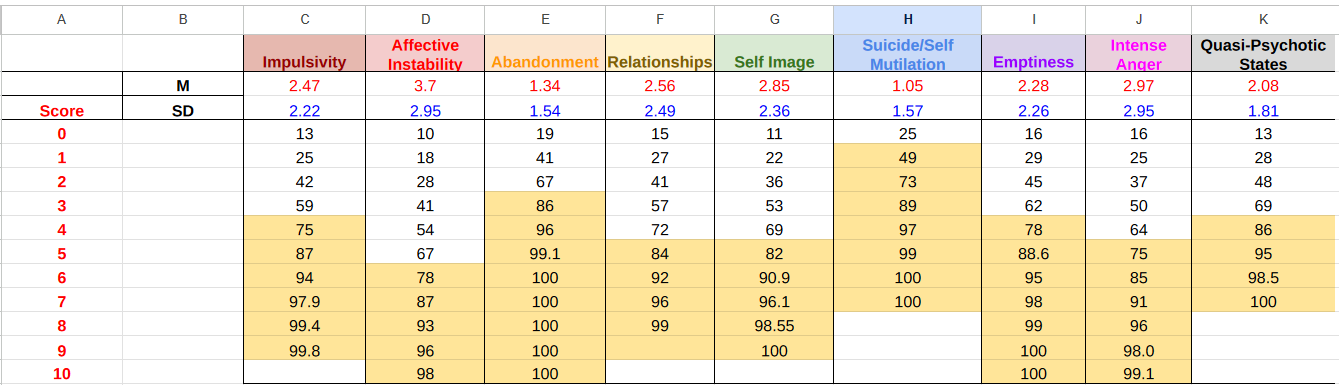

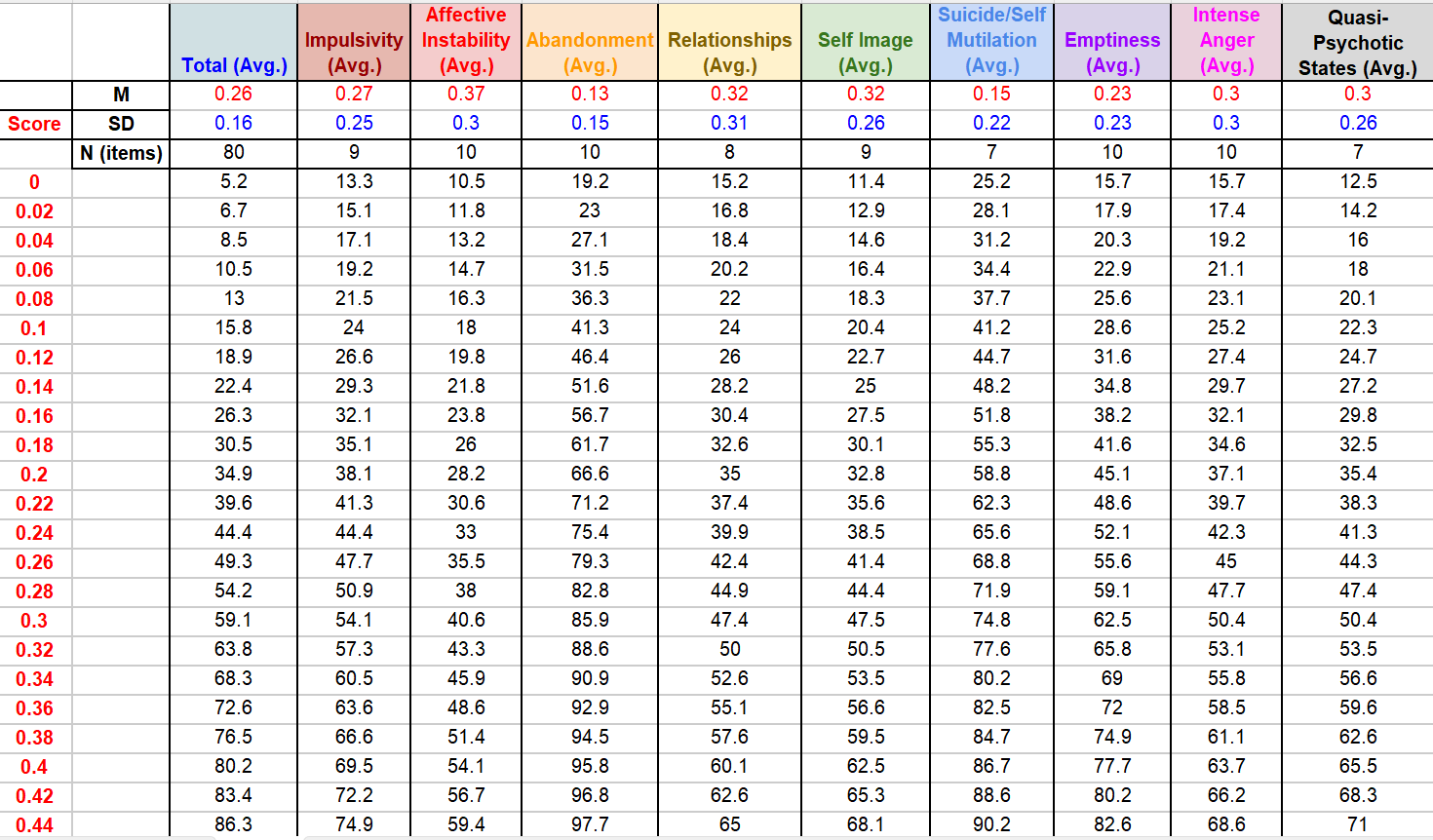

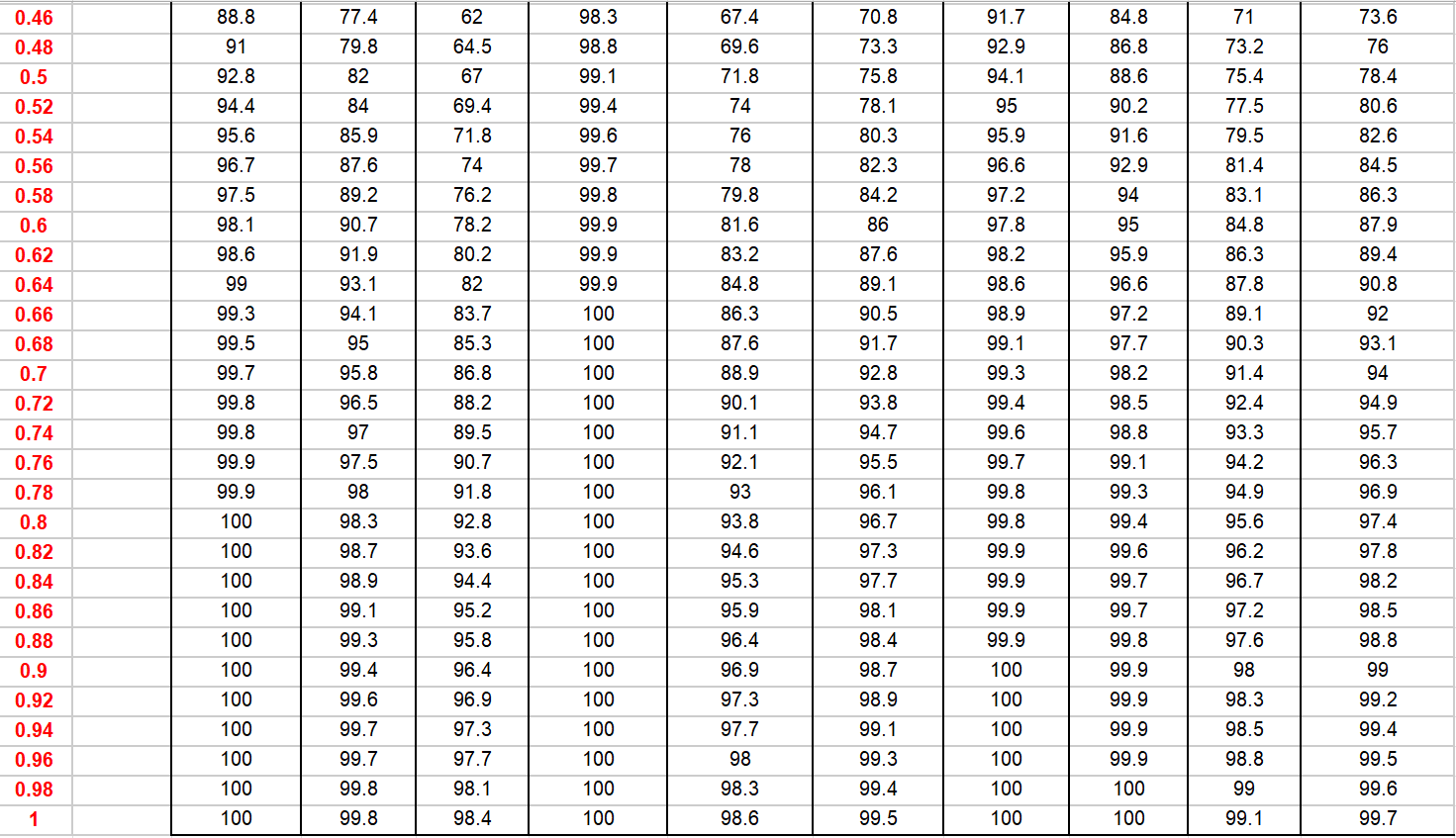

The following table illustrates how total scores on the BES (see Table 1) compare to the normative community and clinical samples (Duarte et al., 2015; Leone et al., 2018). Each score is accompanied by a corresponding normative community and clinical percentile, indicating the percentage of individuals who scored the same or lower. For instance, a score of 16 falls at the 91st percentile in the normative community and the 21st percentile in the clinical sample. This indicates that 91% of people in the normative community group and 21% of people in the clinical group scored 16 or lower. These graphs are instrumental in contextualising an individual’s total scores on the BES, providing a clearer understanding of their standing relative to other individuals in the community and to those with binge-eating disorder.

Table 1

Developer

Gormally, J., Black, S., Daston, S., & Rardin, D. (1982). The assessment of binge-eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors, 7(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7

References

Brownley, K. A., Berkman, N. D., Peat, C. M., Lohr, K. N., Cullen, K. E., Bann, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Binge-Eating Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(6), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2455

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Ferreira, C. (2015). Expanding binge-eating assessment: Validity and screening value of the Binge-eating Scale in women from the general population. Eating Behaviors, 18, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.03.007

Gormally, J., Black, S., Daston, S., & Rardin, D. (1982). The assessment of binge-eating severity among obese persons. Addictive Behaviors, 7(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7

Marcus, M. D., Wing, R. R., & Lamparski, D. M. (1985). Binge-eating and dietary restraint in obese patients. Addictive Behaviors, 10(2), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(85)90022-X

Leone, A., Vignati, L., Battezzati, A., De Amicis, R., Ponissi, V., Beggio, V., Bedogni, G., Vanzulli, A., & Bertoli, S. (2018). Association of Binge-eating Behavior with Total and Abdominal Adipose Tissue in a Large Sample of Participants Starting a Weight Loss or Maintenance Program. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 37(8), 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2018.1463184

Pasold, T. L., McCracken, A., & Ward-Begnoche, W. L. (2014). Binge eating in obese adolescents: Emotional and behavioral characteristics and impact on health-related quality of life. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(2), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104513488605

Telch, C. F., & Stice, E. (1998). Psychiatric Comorbidity in Women With Binge-eating Disorder: Prevalence Rates From a Non-Treatment-Seeking Sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 768–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.768

Timmerman, G. M. (1999). Binge-eating Scale: Further Assessment of Validity and Reliability. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 4(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.1999.tb00051.x

Yan, H.-Y., Lin, F.-G., Tseng, M.-C. M., Fang, Y.-L., & Lin, H.-R. (2023). The psychometric properties of Binge-eating Scale among overweight college students in Taiwan. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00774-3

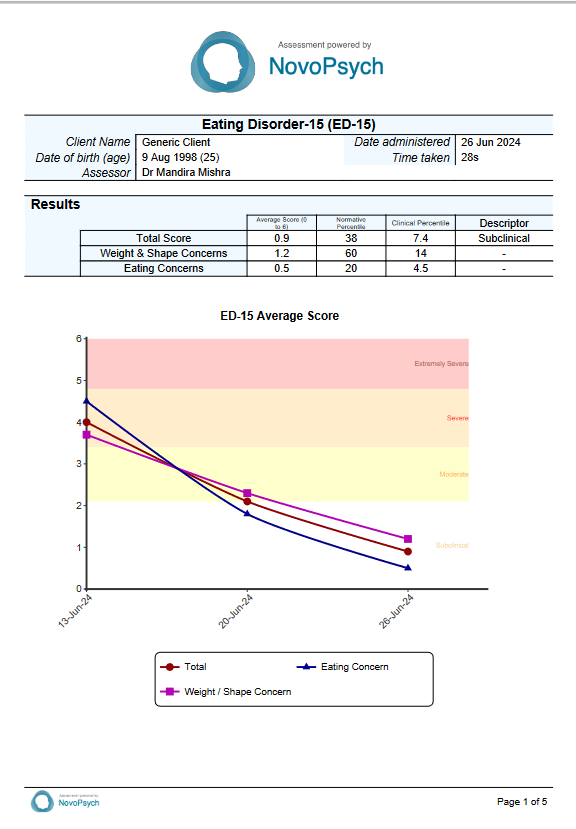

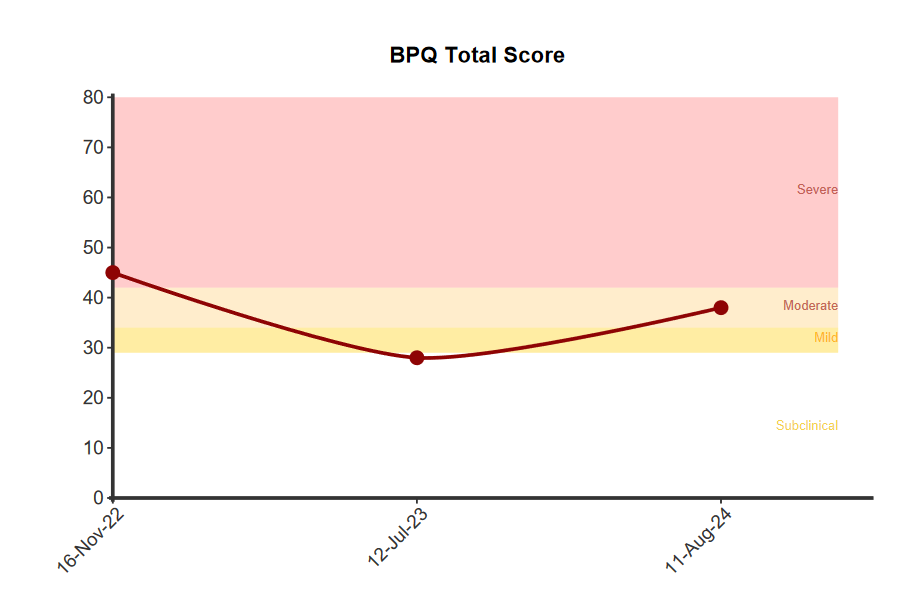

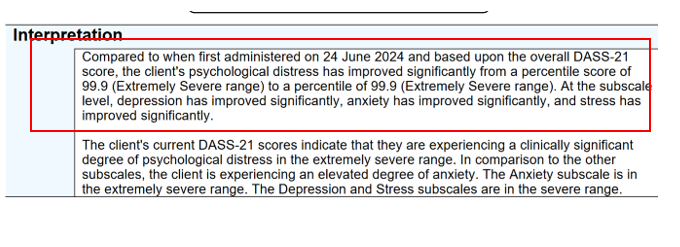

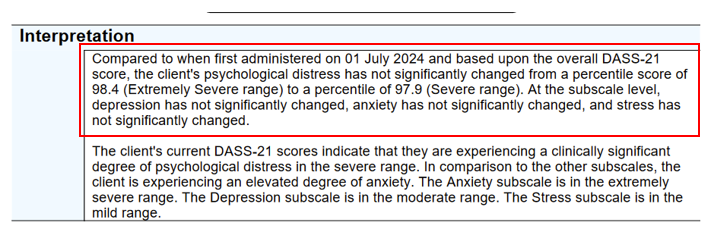

When administered more than once, a clinically important change is defined as a change of 2 points or more (based on

When administered more than once, a clinically important change is defined as a change of 2 points or more (based on

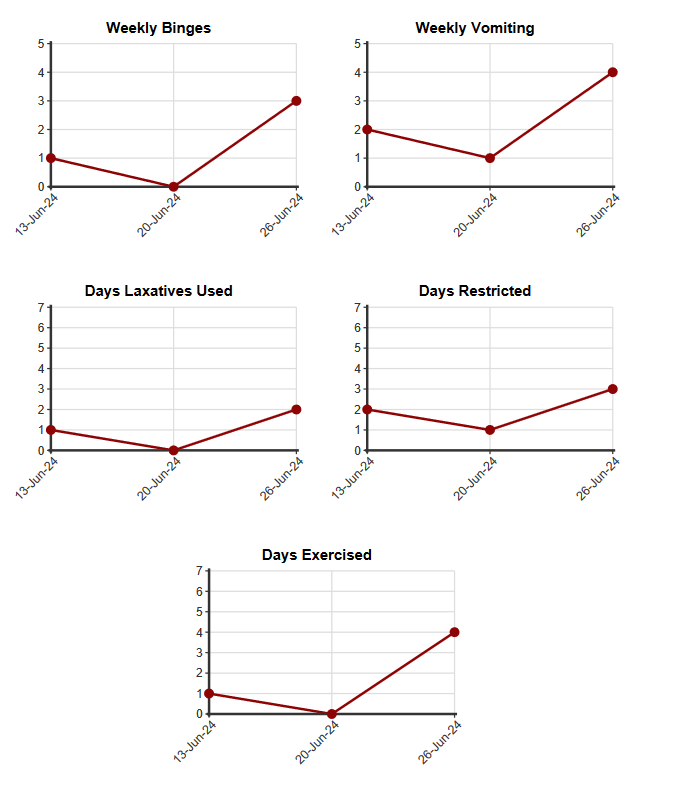

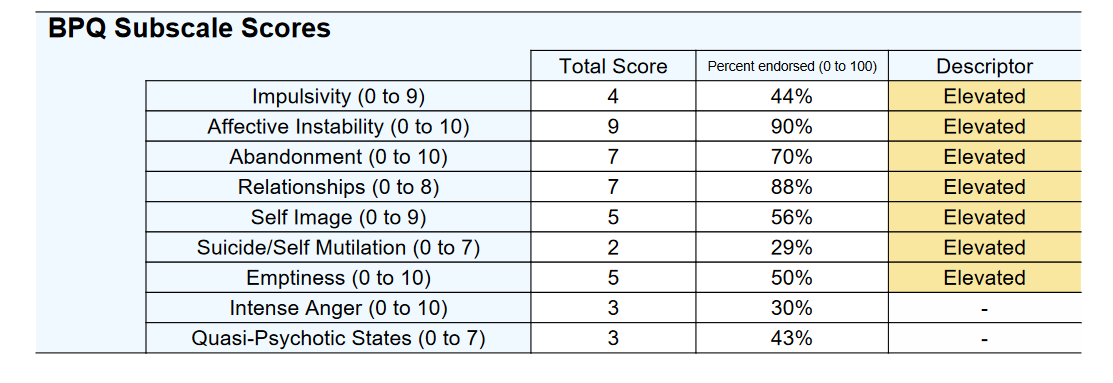

Subscales are presented:

Subscales are presented:  The behavioural items (items 11 to 15) are represented by the frequency they have occurred in the past week.

The behavioural items (items 11 to 15) are represented by the frequency they have occurred in the past week.