The Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS) is a 13-item scale designed to assess alcohol intake, drug use, mental health and emotional well-being.

The Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS) is an assessment designed to assess alcohol and other drug (AOD) use, as well as mental health and emotional well-being (MH) among adults. It is of particular use among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, a population in which it has been extensively validated (Schlesinger et al., 2007).

Multiple reports by the Australian government have indicated the need for a drug, alcohol and mental health screening tool that can facilitate the rapid identification of those at risk for substance abuse and mental health issues in Indigenous and Torres Strait Island populations (Catto & Thomson, 2008; Schlesinger et al., 2007).

The IRIS is suited to meet this need as it assesses alcohol and drug use in addition to mental and emotional well-being. These concepts are reflected in the two subscale domains:

The IRIS is used primarily for screening in primary care, addiction services and correctional facilities or alongside intervention approaches. While the scale does assess the overall burden of drug and alcohol abuse it does not distinguish between different drug types. This limitation prevents the assessment of specific risks associated with certain drugs as this can differ significantly in associated health risks.

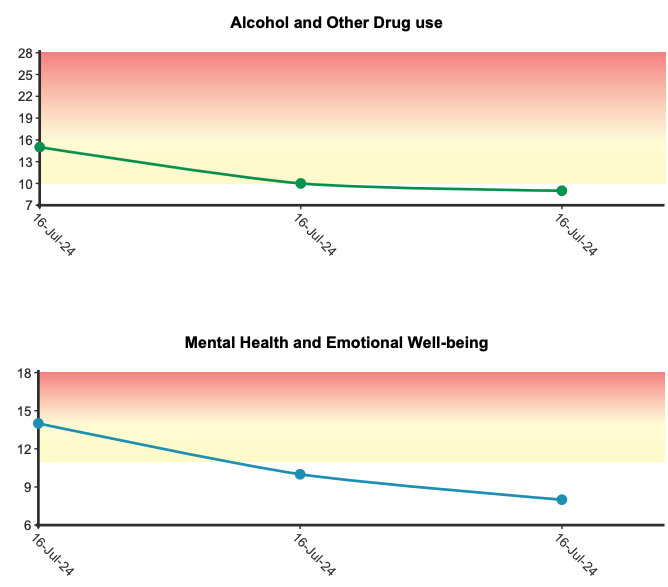

General uses for the IRIS include: screening for alcohol and other drug use and mental health risks, identifying those who may benefit from further assessment or intervention, monitoring changes in dependence levels over time, and supporting the delivery of culturally appropriate health services.

Further notable points relating to the IRIS:

It can be administered both by clinician-rating (Fischer et al., 2021; Marel et al., n.d.) and self-report (Ober et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2012).

It has not yet been validated in younger populations and is intended for use only with adults aged 18 and older (Nori et al., 2013; Stevens et al., 2022).

It is not a diagnostic tool but a risk assessment, high scores are therefore a prompt for further investigation and follow-up (Gray et al., 2019).

Example IRIS items:

Alcohol and other drug risk: (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

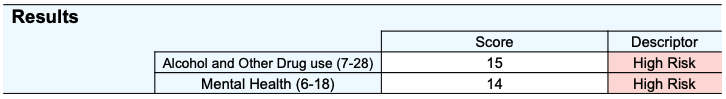

The Alcohol and Other Drug risk subscale ranges from 7-28, with higher scores reflecting a greater likelihood of problematic alcohol and drug use as well as dependence. Scores of 10 or more represent clinically significant risk.

Mental health and emotional well-being risk: (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13)

The Mental Health risk subscale ranges from 6-18, with higher scores indicating increased risks of a psychological condition or functional impairment (Schlesinger et al., 2007; Marel et al., n.d.). Scores of 11 or more represent clinically significant risk, with the client being likely to have a ICD-10 depression or anxiety disorder (with a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 84% in relation to a psychiatric interview using ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety disorders).

If administered more than once a line graph will be produced for each subscale score.

The IRIS was validated in remote and urban areas of Queensland, Australia and is suitable for adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, including both males and females. It has also been validated in correctional faculties, AOD rehabilitation services, and community health and primary care settings.

A two-factor structure (AOD risk and MH risk) was established in the initial validation study by Schlesinger and colleagues (2007) via exploratory factor analysis. This structure has been subsequently supported by later investigation using principal component analysis (Ober et al., 2013). Both IRIS subscales have shown high internal reliability indicated by Cronbach’s alpha values of .84 (AOD), and .79 (MH). Test-retest reliability has also been assessed, with Pearson r values of .79 (AOD) and .81 (MH) indicating strong temporal stability (Schlesinger et al., 2007).

The scale has demonstrated satisfactory convergent validity, with appropriate correlations to other established measures of substance abuse and mental health such as the Severity of Dependence Scale, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire, the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, and the Self-Report Questionnaire. Further evidence was observed in area under the curve values from a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. The observed patterns showed the subscales discriminating as expected. Specifically, the AOD score was more likely to predict ICD-10 rated substance use as opposed to depression/anxiety, and the MH score was more likely to predict ICD-10 rated depression/anxiety as opposed to substance use (Ober et al., 2013).

Normative data is available in a sample (n=154) mostly indigenous (88%) Australians receiving AOD specialist rehabilitation services. This data helps in interpreting scores within the context of response patterns when used on similar populations (Shakeshaft et al., 2018).

Among this sample they found the following means and standard deviations:

Alcohol and Other Drug risk: Mean = 22.30, SD 4.96

Mental Health and Emotional Well-being risk: Mean = 11.80, SD 2.83

Receiver operating characteristic analysis was used to determine these cut-off scores using the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire and the Self-Report Questionnaire (Schlesinger et al., 2007). For the AOD subscale, a score of 10 provided a high specificity of 86% and a moderate sensitivity of 65%. In other words, the AOD subscale is more accurate at correctly identifying low risk clients. Conversely, this subscale is weaker at correctly classifying high risk clients, therefore high scorers should be viewed with less confidence that their classification is correct.

Schlesinger, C. M., Ober, C., McCarthy, M. M., Watson, J. D., & Seinen, A. (2007). The development and validation of the Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS): A 13-item screening instrument for alcohol and drug and mental health risk. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(2), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230601146611

Catto, M. , & Thomson, N. J. (2008). Review of illicit drug use among Indigenous peoples. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 8(4), 32.

Fischer, J. A., Roche, A. M., & Duraisingam, V. (2021). An overview of the Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS): Description, strengths and knowledge gaps. National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction (NCETA), Flinders University.

Gray, D., Cartwright, K., Stearne, A., Saggers, S., Wilkes, E., Wilson, M., Harford-Mills, M. (2019). Plain language review of the harmful use of alcohol among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

Lee, K. S., Dawson, A., & Conigrave, K. M. (2013). The role of an Aboriginal women’s group in meeting the high needs of clients attending outpatient alcohol and other drug treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(6), 618-626. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12068

Nori, A., Piovesan, R., O’Connor, J., Graham, A., Shah, S., Rigney, D., McMillan, M., & Brown, N. (2013). ‘Y Health – Staying Deadly’: An Aboriginal youth focussed translational action research project. Australian National University.

Schlesinger, C., Ober, C., McCarthy, M., et al. (2007). The development and validation of the Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS): a 13-item screening instrument for alcohol and drug and mental health risk. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(2), 109-117.

Shakeshaft, A., Clifford, A., James, D., Doran, C., Munro, A., Patrao, T., Bennett, A., Binge, C., Bloxsome, T., Coyte, J., Edwards, D., Henderson, N., & Jeffries, D. (2018). Understanding clients, treatment models and evaluation options for the NSW Aboriginal Residential Healing Drug and Alcohol Network (NARHDAN): A community-based participatory research approach. Prepared by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (UNSW Sydney) for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra, ACT.

Stevens, M. W. R., Barry, D., Bertossa, S., Thompson, M., & Ali, R. (2022). First-stage development of the Pitjantjatjara translation of the World Health Organization’s Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Journal of the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, 3(4), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.14221/aihjournal.v3n4.2

Sun, J., Buys, N., Tatow, D., & Johnson, L. (2012). Ongoing health inequality in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in Australia: Stressful event, resilience, and mental health and emotional well-being difficulties. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 2(1), 38-45. http://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120201.06

Marel, C., Siedlecka, E., Fisher, A., Gournay, K., Deady, M., Baker, A., Kay-Lambkin, F., Teesson, M., Baillie, A., Mills, K. L. (n.d.). ‘ Identifying co-occurring conditions’, Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://comorbidityguidelines.org.au/part-b-responding-to-cooccurring-conditions/b3-identifying-cooccurring-conditions

Ober, C., Dingle, K., Clavarino, A., Najman, J. M., Alati, R., & Heffernan, E. B. (2013). Validating a screening tool for mental health and substance use risk in an Indigenous prison population. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(6), 611-617. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12063

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved