The General Behaviour Inventory-Revised (GBI-R) is a 73-item self-report tool designed to assess bipolar disorder (Depue et al., 1989). It measures the frequency, intensity, and duration of symptoms associated with bipolar disorder type I and II, as well as cyclothymia.

The items on the GBI are distributed across two subscales:

The GBI is useful for assessing bipolar disorder risk and monitoring symptoms in clinical practice. It has been validated across diverse demographics, including adolescents (13+), adults, in community health and psychiatric settings (Danielson et al., 2003).

The inventory is useful for screening for subtypes of bipolar disorders:

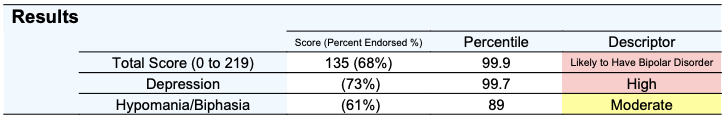

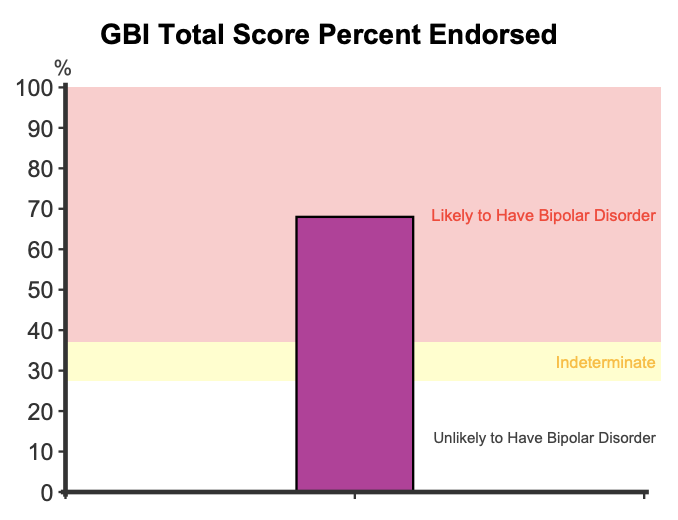

The GBI total score ranges from 0 to 219. The GBI total score reflects the frequency and intensity of symptoms related to bipolar disorder.

Score is also expressed as the “percent endorsed”, which uses a binary scoring where “Never or Hardly Ever” and “Sometimes” are not endorsed, while responses “Often” and “Very Often or Almost Constantly” are considered endorsed. Percent endorsed convert scores to 0% to 100%.

Total scores are classified into three risk categories:

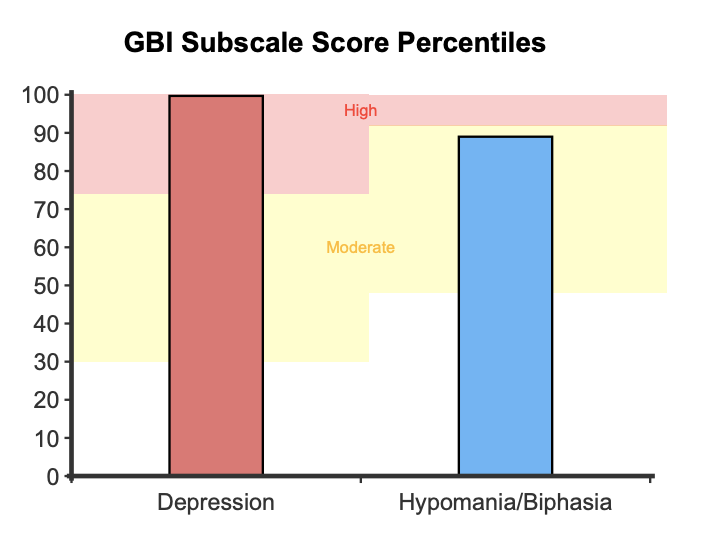

The subscale scores are also computed using the Binary scoring system, where scores are expressed as the percent of items endorsed as occurring “Often” and “Very Often or Almost Constantly”:

A percentile is used to contextualise a respondent’s score compared to the normative community sample. The community sample represents the typical level of mood-related symptoms found in the general population (Bullock et al., 2011; Pendergast et al., 2014). A percentile of 50 suggests typical (and relatively healthy) experience of psychomotor energy, whereas a percentile of 80 indicates that the respondent scores higher than 80 percent of individuals, indicating some symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder.

The horizontal graphs presents the total score (0 to 219, scored using the likert method) and percent endorsed score for the subscales (from 0 to 100%). These graphs shows scores in comparison to the normative community and clinical distributions, with shaded areas around the two middle quartiles (between the 25th and 75th percentile). The clinical distribution represents individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder (Bullock et al., 2011; Pendergast et al., 2014). This graph helps contextualise patterns of responding in comparison to the distribution of responses among community samples and those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Pendergast et al., 2014).

For the total score, when 37% of symptoms are endorsed the scale has a sensitivity of .90, meaning it correctly identifies 90% of true cases (Klein et al., 1986). At this level, its specificity is .98, indicating it correctly identifies 98% of non-cases.

Higher scores on the GBI may suggest the presence of bipolar disorder, which frequently coexists with other psychiatric conditions. For instance, research indicates that one in six adults with bipolar disorder also has ADHD (Schiweck et al., 2021). People with ADHD also score higher on the GBI than the general public. Other commonly associated disorders include autism spectrum disorder, borderline personality disorder, and substance use disorders (Menezes et al., 2019; Skokauskas & Frodl, 2015). Recent evidence highlights the GBI’s effectiveness in differentiating bipolar disorder from conditions such as unipolar depression and ADHD, making it a valuable tool for addressing comorbidity challenges in psychiatric assessments (Pendergast et al., 2014).

The GBI’s psychometric properties have been evaluated extensively, demonstrating it as a reliable and valid tool for assessing symptoms of bipolar disorder. The GBI captures both the core behavioural symptoms and dimensions like intensity, duration, frequency, and rapid shifts in mood. The items on the GBI were developed based on several sources:

During its development, the GBI was evaluated against a binomial classification of bipolar “cases” and “non-cases,” making it effective for identifying individuals at risk of bipolar disorder versus those with subclinical mood variations or other mood disorders. Recent research suggests that the GBI’s effectiveness could be improved by reorganising its items into more homogeneous subscales (Youngstrom et al., 2001). While earlier studies pointed to a single general factor accounting for most variance (Depue et al., 1981), newer analyses (Danielson et al., 2003; Depue et al., 1989; Pendergast et al., 2015; Youngstrom et al., 2001, 2013) support a two-factor structure, comprising of the following subscales:

In the original study (Depue et al., 1981), analysis was performed on a non-clinical sample of 850 undergraduate students (51.5% female) with an age range of 18 to 32 years old. The majority of participants (90%) were 22 years of age or younger. The GBI exhibited strong construct validity, as evidenced by its significant correlation with clinician-rated assessments of mood disturbance (Depue et al., 1981). The scale showed strong overall internal consistency (alpha = .94) (Depue et al., 1981; 1989) and test-retest reliability over 15 weeks was reported to be 0.73 (Depue et al., 1981).

The Hypomania and Depressive scale scores demonstrate strong psychometric properties across various samples, including internal reliability alphas above .90, test-retest reliabilities over .70, robust predictive validity, and satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity (Youngstrom, 2008; Youngstrom et al., 2013).

The GBI uses two methods of scoring: Binary and Likert.

Using the binary scoring method the responses “Never or Hardly Ever” and “Sometimes” are scored as 0, and responses “Often” and “Very Often or Almost Constantly” are scored as 1. In NovoPsych, subscales are scored using the binary method, yielding a “percent endorsed” metric.

Alternatively, using the Likert scoring method, the response “Never or Hardly Ever” is scored as 0, “Sometimes” is scored as 1, “Often” is scored as 2, and “Very Often or Almost Constantly” is scored as 3. NovoPsych uses both the likert method (score range = 0 to 219) and binary method (percent endorsed) for the total score.

When using the Binary scoring, the GBI uses a two-threshold system, with one threshold for likely cases and another for non-cases, to classify individuals based on their total scores. This two-cut-off score system divides scores into three categories:

With the primary cut-off of 27 (37% endorsement), for bipolar conditions, the scale has a sensitivity of .90, meaning it correctly identifies 90% of true cases. Its specificity was .98 indicating it correctly identifies 98% of non-cases (Klein et al., 1986). In the study by Depue et al. (1981), a cut score of 27 secured a Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of 0.98, indicating that 98% of individuals who receive a positive result on the scale (indicating the presence of a condition) truly have bipolar disorder. Finally, the Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of the scale is .87, indicating that 87% of the individuals who receive a negative test result (indicating they do not have the condition) are correctly identified as not having bipolar disorder (Waugh et al., 2014). However, the false negative rate, where actual cases are missed, was 9% for scores below 19 and increased for scores in the 20-26 range (Depue et al., 1981).

For the depression subscale (range 0 to 46 as per Binary scoring method), a range of scores from 0 to 2 (0% to 4%) are categorised as “Low”, 3 to 14 (5% to 31%) as “Moderate”, and 15 to 46 (32% to 100%) as “High”.

For the hypomania/biphasia subscale (range 0 to 28 as per Binary scoring method), scores from 0 to 5 (0% to 18%) are categorised as “Low”, 6 to 19 (19% to 68%) are categorised as “Moderate”, and 20 to 28 (69% to 100%) are categorised as “High” (Pendergast et al., 2014).

Although the study by Pendergast et al., (2014) does not provide sensitivity and specificity data directly, it measured related constructs through Diagnostic Likelihood Ratios (DLRs). Diagnostic Likelihood Ratios (DLRs) are tools that examine how much a test result changes the chances that someone has a specific condition (Straus et al., 2011). A DLR of 1 is neutral, DLR < 1 decreases the likelihood of the condition, and DLR > 1 increases the likelihood (Straus et al., 2011). For the hypomania/biphasia scale, the following DLRs were reported for the severity categories when comparing individuals with and without bipolar disorder:

A similar analysis was conducted on the depression subscale, however, the comparison was made between individuals with and without any mood disorder:

The sample used to compute normative percentiles for the total score consisted of 87 Australian participants (68% female) with a mean age of 26.3. (Bullock et al., 2011). The study used the Likert scoring method. The GBI scores were divided between low and high scorers, so a pooled average was calculated to represent the typical score of an individual in the normative sample. For the total score,

Two other samples were used for comparison purposes at the subscale level. In Sample 1, a total of 359 adolescents (69.6% female), aged 14 to 19 years (M = 18.35, SD = 1.52), participated in the Teen Emotion and Motivation (TEAM) project (Alloy et al., 2012a). Sample 2 consisted of 614 university students (33.2% female), aged 18 to 24 years (M = 19.63, SD = 1.76), who were part of the Longitudinal Investigation of Bipolar Spectrum (LIBS) project (Alloy et al., 2008; 2012b). The above samples were used in the study by Pendergast et al., (2014), which analysed both individuals from the general public sample and those with bipolar disorder. This study used the binary scoring method, meaning that responses “Never or Hardly Ever” and “Sometimes” were scored as 0, and responses “Often” and “Very Often or Almost Constantly” were scored as 1 (Pendergast et al., 2014). The means and standard deviations for both the subscales in Pendergast et al. (2014) are as follows:

Depue, R. A., Krauss, S., Spoont, M. R., & Arbisi, P. (1989). General Behavior Inventory Identification of Unipolar and Bipolar Affective Conditions in a Nonclinical University Population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.98.2.117

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Walshaw, P. D., Cogswell, A., Sylvia, L. G., Hughes, M. E., Iacoviello, B. M., Whitehouse, W. G., Urosevic, S., Nusslock, R., & Hogan, M. E. (2008). Behavioral approach system (BAS) and behavioral inhibition system (BIS) sensitivities and bipolar spectrum disorders: Prospective prediction of bipolar mood episodes. Bipolar Disorders, 10(3), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00547.x

Alloy, L. B., Bender, R. E., Whitehouse, W. G., Wagner, C. A., Liu, R. T., Grant, D. A., & Abramson, L. Y. (2012a). High behavioral approach system (BAS) sensitivity, reward responsiveness, and goal-striving predict first onset bipolar spectrum disorders: A prospective behavioral high-risk design. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024680

Alloy, L. B., Urosevic, S., Abramson, L. Y., Jager-Hyman, S., Nusslock, R., Whitehouse, W. G., & Hogan, M. E. (2012b). Progression along the bipolar spectrum: A longitudinal study of predictors of conversion from bipolar spectrum conditions to bipolar I and II disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023973

Bullock, B., Judd, F., & Murray, G. (2011). Social rhythms and vulnerability to bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.006

Danielson, C. K., Youngstrom, E. A., Findling, R. L., & Calabrese, J. R. (2003). Discriminative Validity of the General Behavior Inventory Using Youth Report. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(1), 29-. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021717231272

Depue, R. A. (1981). A behavioral paradigm for identifying persons at risk for bipolar depressive disorder: A conceptual framework and five validation studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90(5), 381–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.90.5.381

Depue, R. A., Krauss, S., Spoont, M. R., & Arbisi, P. (1989). General Behavior Inventory Identification of Unipolar and Bipolar Affective Conditions in a Nonclinical University Population. Journal of Abnormal Psychology (1965), 98(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.98.2.117

Klein, D. N., Depue, R. A., & Slater, J. F. (1986). Inventory Identification of Cyclothymia: IX. Validation in Offspring of Bipolar I Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43(5), 441–445. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050043005

Munesue, T., Ono, Y., Mutoh, K., Shimoda, K., Nakatani, H., & Kikuchi, M. (2008). High prevalence of bipolar disorder comorbidity in adolescents and young adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A preliminary study of 44 outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 111(2), 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.015

Pendergast, L. L., Youngstrom, E. A., Merkitch, K. G., Moore, K. A., Black, C. L., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2014). Differentiating Bipolar Disorder From Unipolar Depression and ADHD: The Utility of the General Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035138

Pendergast, L. L., Youngstrom, E. A., Brown, C., Jensen, D., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2015). Structural Invariance of General Behavior Inventory (GBI) Scores in Black and White Young Adults. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000020

Schiweck, C., Arteaga-Henriquez, G., Aichholzer, M., Edwin Thanarajah, S., Vargas-Cáceres, S., Matura, S., Grimm, O., Haavik, J., Kittel-Schneider, S., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Faraone, S. V., & Reif, A. (2021). Comorbidity of ADHD and adult bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 124, 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.017

Skokauskas, N., & Frodl, T. (2015). Overlap between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Bipolar Affective Disorder. Psychopathology, 48(4), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1159/000435787

Straus, SE.; Glasziou, P.; Richardson, WS.; Haynes, RB (2011). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. (4th ed.) New York: Churchill Livingstone.

Waugh, M. J., Meyer, T. D., Youngstrom, E. A., & Scott, J. (2014). A review of self-rating instruments to identify young people at risk of bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 160, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.019

Youngstrom, E. A., Findling, R. L., Danielson, C. K., & Calabrese, J. R. (2001). Discriminative Validity of Parent Report of Hypomanic and Depressive Symptoms on the General Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.267

Youngstrom, E. A., Frazier, T. W., Demeter, C., Calabrese, J. R., & Findling, R. L. (2008). Developing a 10-item mania scale from the Parent General Behavior Inventory for children and adolescents. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 69(5), 831–839. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v69n0517

Youngstrom, E. A., Murray, G., Johnson, S. L., & Findling, R. L. (2013). The 7 Up 7 Down Inventory: A 14-Item Measure of Manic and Depressive Tendencies Carved From the General Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1377–1383. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033975

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved