The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), used to screen for depression in adults aged 55 and older, consists of 15 items that assess mental health based on feelings over the past week (Yesavage & Sheikh, 1986).

It can be administered to healthy, medically ill, or cognitively impaired older adults, and is suitable for use in both community and hospital settings. The GDS-15 consists of two subscales:

The GDS-15 is well-suited for elderly populations due to its brevity and straightforward yes/no response format. Despite its simple design, the GDS-15 has been shown to have comparable accuracy to longer, more complex scales like the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRS-D), the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Depression Adjective Check List (DACL) (Yesavage & Sheikh, 1986).

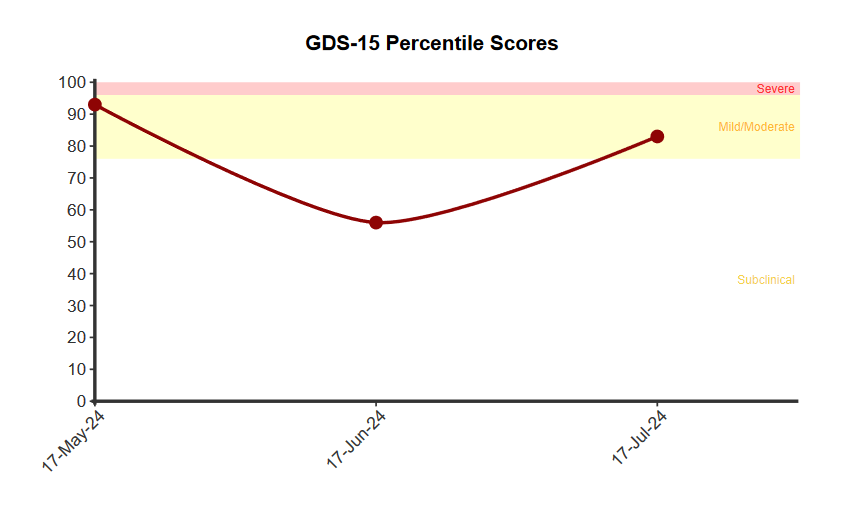

Although the scale may be used across older adults with varying levels of cognitive abilities, recent studies suggest that it may be more accurate for older adults with typical cognitive functioning (Park & Kwak, 2020). The GDS is suitable as an outcome monitoring tool to assess change in depressive symptoms over time (Greenberg, 2007).

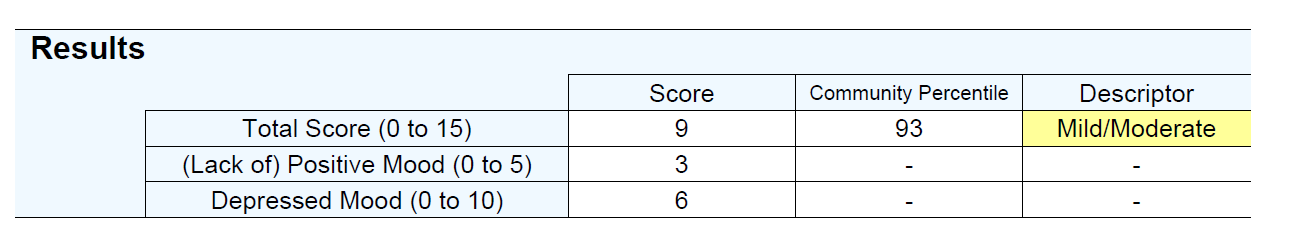

The GDS-15 has a total score range of 0 to 15, where higher scores reflect more severe levels of depression. Scores of 6-10 indicate mild to moderate depression, while scores of 11-15 indicate severe depression (Friedman et al., 2005). Two subscales are presented:

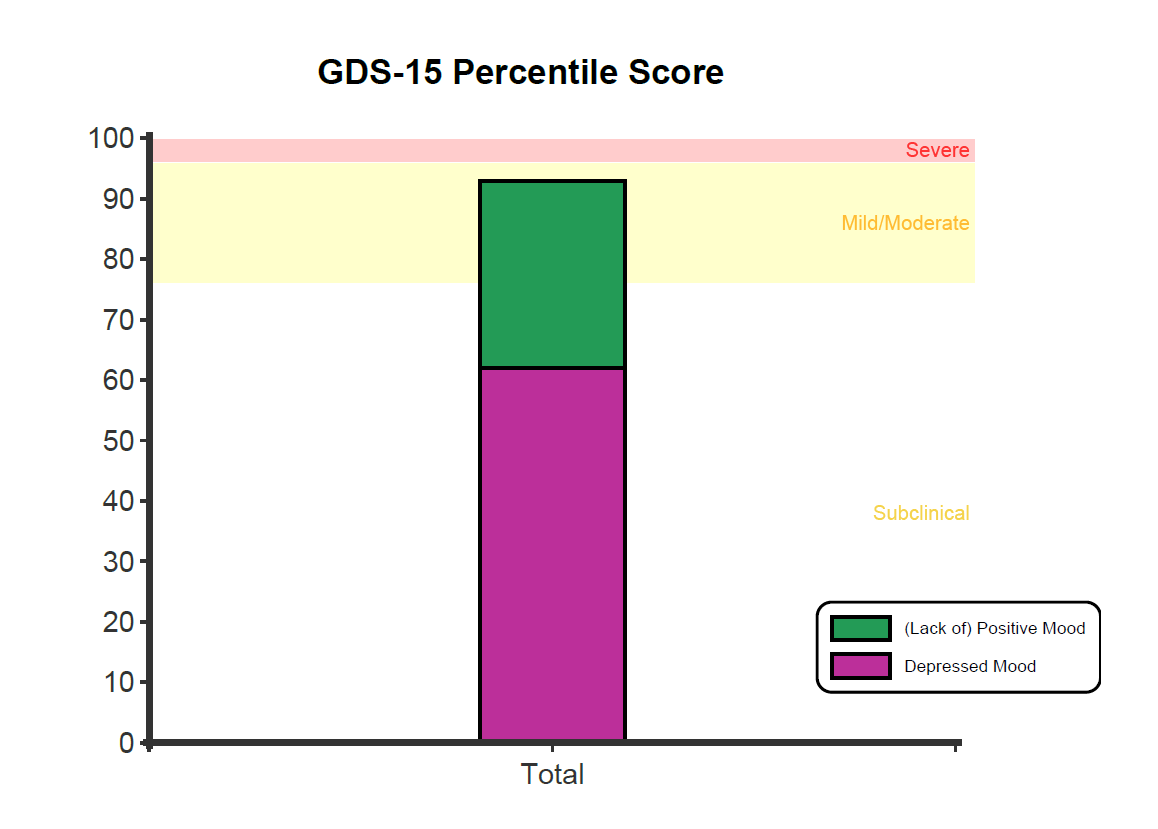

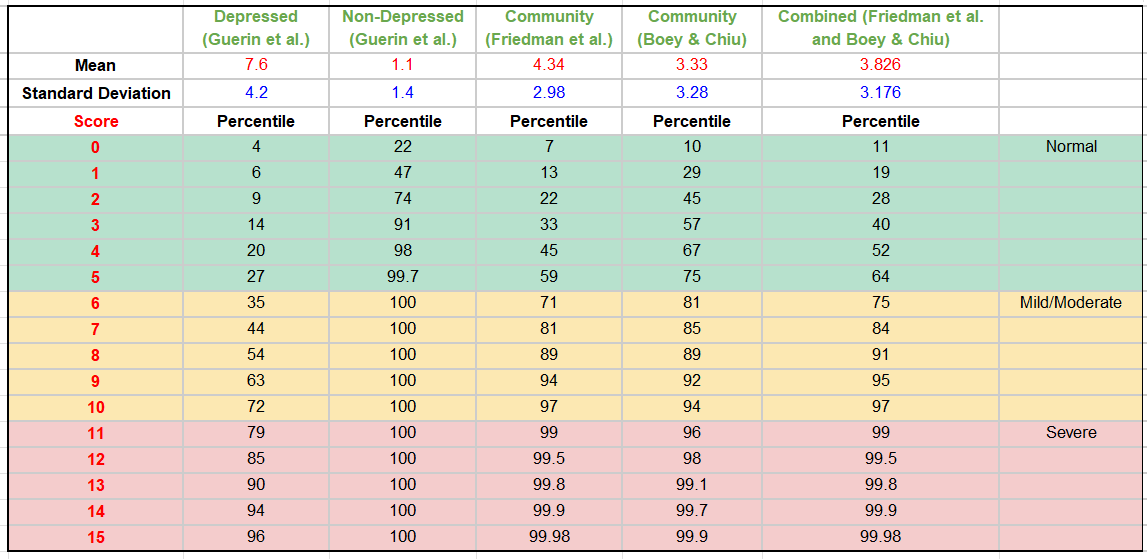

A percentile is presented showing the respondent’s score in comparison to normative responses for older adults. A percentile of 50 represents typical (and healthy) patterns of responding. Conversely, a percentile of 99 indicates the respondent scores higher than 99 percent of older adults, indicating severe depressive symptoms.

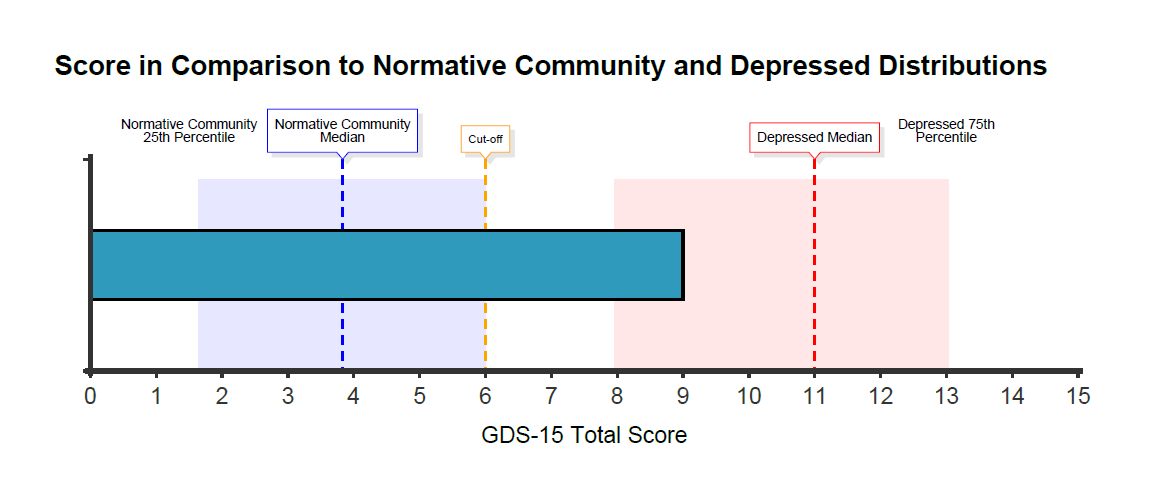

The score is presented in comparison to the normative community and depressed distributions, with shaded areas around the two middle quartiles (between the 25th and 75th percentile). This graph helps contextualise scores in comparison to the distribution of responses among non-clinical and clinical samples. A cutoff score of 6 indicates the point at which symptoms are defined as indicative of clinical depression, with a sensitivity of 81.45% and specificity of 75.36% (Friedman et al., 2005). When administered more than once, a clinically important change is defined as a change of 2 points or more (based on Minimally Important Difference calculations).

When administered more than once, a clinically important change is defined as a change of 2 points or more (based on Minimally Important Difference calculations).

The GDS-15 was initially developed in English in 1986 as a shorter version of the original GDS-30 (Yesavage et al., 1982). For the initial development and validation of the scale, a team of geriatric psychiatry experts selected 100 questions covering various depression-related topics and formatted them in a yes/no style for clarity. These questions were tested on 47 elderly subjects, including both community-dwelling individuals and those hospitalised for depression. The 30 questions with the highest correlations to the total score were chosen to create the GDS (Yesavage et al.,1982).

There are also shorter versions of the GDS-15, such as the GDS-10, GDS-5, and GDS-4, which include questions that have shown strong correlations with depression in validation studies of the full scale (D’ath et al., 1994). Notably, the shorter forms, such as the GDS-15, exhibit better diagnostic performance compared to the full 30-item GDS (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020).

For the abridged version, the study by Wongpakaran et al., (2013) conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the GDS-15, examining 237 older adults (64% female) in long-term care with a mean age of 71.5 years (SD ± 7.4). A two-factor solution was found to be the most theoretically reasonable, explaining 46.6% of the total variance. This solution included factors for:

The GDS-15 demonstrated moderate but acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75) (Wongpakaran et al., 2013). In another study, the test-retest reliability results showed substantial agreement and excellent consistency between repeated test administrations (Snellman et al., 2024).

The GDS-15 exhibited good convergent validity, correlating strongly with both the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The GDS-15 is highly effective at differentiating between subclinical mental states, minor depressive disorder, and major depressive disorder. Notably, the GDS-15’s discriminatory power was comparable to that of the BDI and PHQ-9 for multi-category classification (Shin et al., 2019).

Three distinct types of samples were used for comparison: depressed samples consisting of individuals diagnosed with depression (Guerin et al., 2018), non-depressed samples consisting of individuals without depression (Costa et al., 2018; Guerin et al., 2018), and community samples consisting of community-dwelling older adults (Boey & Chiu, 1998; Friedman et al., 2005).

In the study by Guerin et al. (2018), participants without significant histories of depression or other psychiatric disorders were included as healthy controls (n = 83; Mean age = 68.1; SD = 7.9; 52% male). Those diagnosed with major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or bipolar depression according to DSM-IV criteria were categorised as clinically depressed (n = 29; Mean age = 64.7; SD = 8.3; 38% male). The means and standard deviations of the depressed and non-depressed groups are as follows:

A community-dwelling sample consisted of 960 cognitively intact adults aged 65 and older, with a mean age of 79.3 years (SD = 7.4), of which 75% were female (Friedman et al., 2005).

A second community sample (Boey & Chiu, 1998) of 995 older adults produced a similar pattern of responses.

Data from these two community samples were combined to produce normative data used by NovoPsych to produce community percentiles.

The percentile table below illustrates how a score compares to the depressed, non-depressed, and normative community samples. Each score is accompanied by a corresponding percentile, indicating the percentage of individuals who scored the same or lower. For instance, a Total score of 8 corresponds to the 91st percentile in the combined normative community sample, signifying that 91% of the sample had a total score of 8 or lower. These graphs are instrumental in contextualising an individual’s depression score, providing a clearer understanding of their standing relative to depressed, non-depressed, and normative community populations.

Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. O.(1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4

Yesavage, J. A., & Sheikh, J. I. (1986). 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Version. Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1–2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

Boey, K. W., & Chiu, H. F. K. (1998). Assessing psychological well-being of the old-old?: A comparative study of GDS-15 and GHQ-12. Clinical Gerontologist, 19(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v19n01_06

Costa, M. V., Diniz, M. F., Nascimento, K. K., Pereira, K. S., Dias, N. S., Malloy-Diniz, L. F., & Diniz, B. S. (2016). Accuracy of three depression screening scales to diagnose major depressive episodes in older adults without neurocognitive disorders. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 38(2), 154–156. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1818

D’Ath, P., Katona, P., Mullan, E., Evans, S., & Katona, C. (1994). Screening, Detection and Management of Depression in Elderly Primary Care Attenders. I: The Acceptability and Performance of the 15 Item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the Development of Short Versions. Family Practice, 11(3), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/11.3.260

Davidson, T. E., McCabe, M. P., Knight, T., & Mellor, D. (2012). Biopsychosocial factors related to depression in aged care residents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 142(1), 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.019

Friedman, B., Heisel, M. J., & Delavan, R. L. (2005). Psychometric Properties of the 15-Item Geriatric Depression Scale in Functionally Impaired, Cognitively Intact, Community-Dwelling Elderly Primary Care Patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 53(9), 1570–1576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53461.x

Greenberg, S. A. (2007). How to Try This: Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form. The American Journal of Nursing, 107(10), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000292204.52313.f3

Guerin, J. M., Copersino, M. L., & Schretlen, D. J. (2018). Clinical utility of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) for use with young and middle-aged adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 241, 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1016 j.jad.2018.07.038

Krishnamoorthy, Y., Rajaa, S., & Rehman, T. (2020). Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 87, 104002–104002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.104002

Park, S.-H., & Kwak, M.-J. (2021). Performance of the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 with Older Adults Aged over 65 Years: An Updated Review 2000-2019. Clinical Gerontologist, 44(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2020.1839992

Shin, C., Park, M. H., Lee, S.-H., Ko, Y.-H., Kim, Y.-K., Han, K.-M., Jeong, H.-G., & Han, C. (2019). Usefulness of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) for classifying minor and major depressive disorders among community-dwelling elders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 370–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.053

Snellman, S., Hörnsten, C., Olofsson, B., Gustafson, Y., Lövheim, H., & Niklasson, J. (2024). Validity and test-retest reliability of the Swedish version of the Geriatric Depression Scale among very old adults. BMC Geriatrics, 24(1), 261–261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04869-7

Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., & Van Reekum, R. (2013). The Use of GDS-15 in Detecting MDD: A Comparison Between Residents in a Thai Long-Term Care Home and Geriatric Outpatients. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, 5(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.4021/jocmr1239w

Yesavage, J. A., & Sheikh, J. I. (1986). 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Version. Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1–2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. O. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved