The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-5 (K5) is a 5-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess psychological distress over the past four weeks. The K5 is a shortened version of the K10, and involved wording modifications for certain items to ensure cultural appropriateness and understanding for Indigenous Australians and Torres Strait Island populations. It is designed for Australian indigenous adults aged 16 years and over.

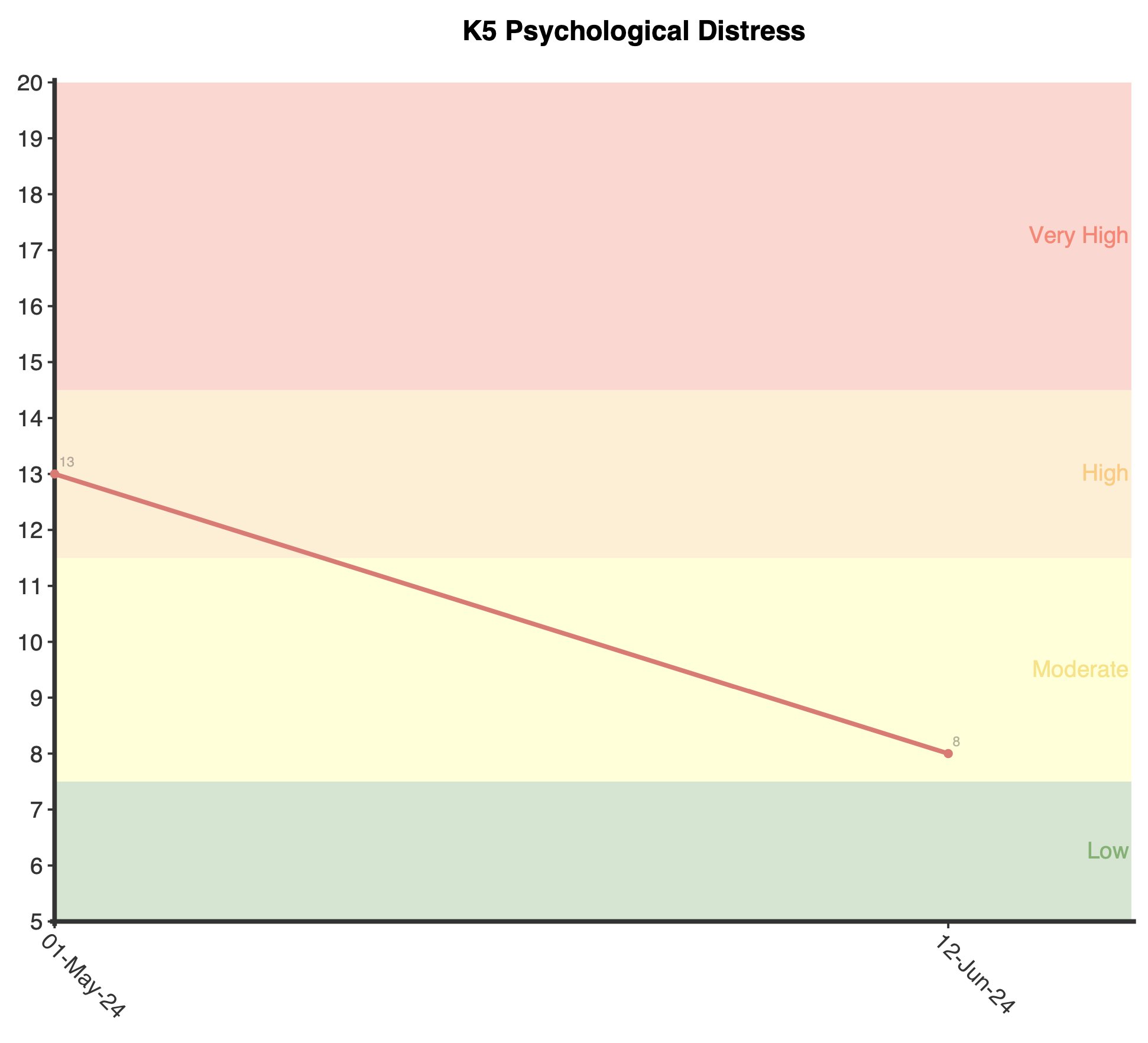

The K5 is considered a non-specific measure, meaning it assesses distress in general rather than specifically targeting depression or anxiety (Kessler & Mroczek, 1992). Questions included in the K5 involve the frequency of feelings such as nervousness, hope, restlessness, effort and sadness. The scale’s usefulness lies in its short administration time, allowing it to easily be integrated into routine assessment. Its primary functions are to monitor changes in patients over time, evaluate the efficacy of a treatment or serve as a screening indicator of anxiety or depression (Brinckley et al 2021).

K5 scores have been observed to be associated with poorer quality of life (McNamara et al., 2014) and well-being (Redman-Mclaren et al 2017), as well as higher self-reported mental illnesses and health issues (Brinckley et al 2021; Stolk et al 2014). The scale has been used in a range of investigations, such as community-care interventions (Burgess, 2009) and distress related to health conditions (LaGrappe et al 2022).

Australia’s Primary Health Networks (PHNs) recommended the K5 for use as an alternative to the K10 for Aboriginal people, and makes up part of the PHN minimum dataset.

Example K5 items:

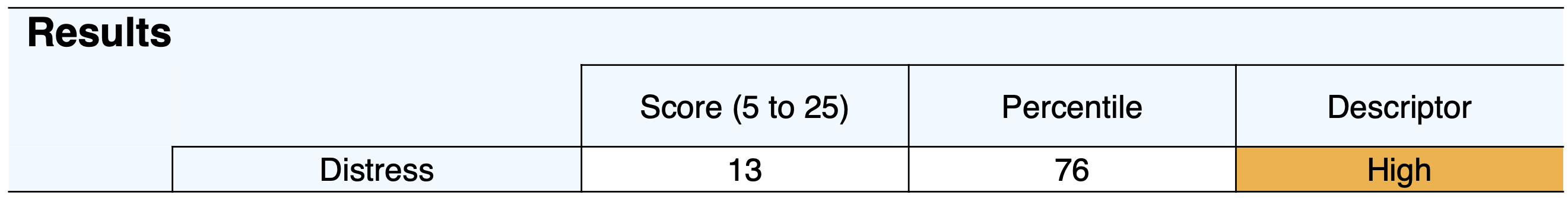

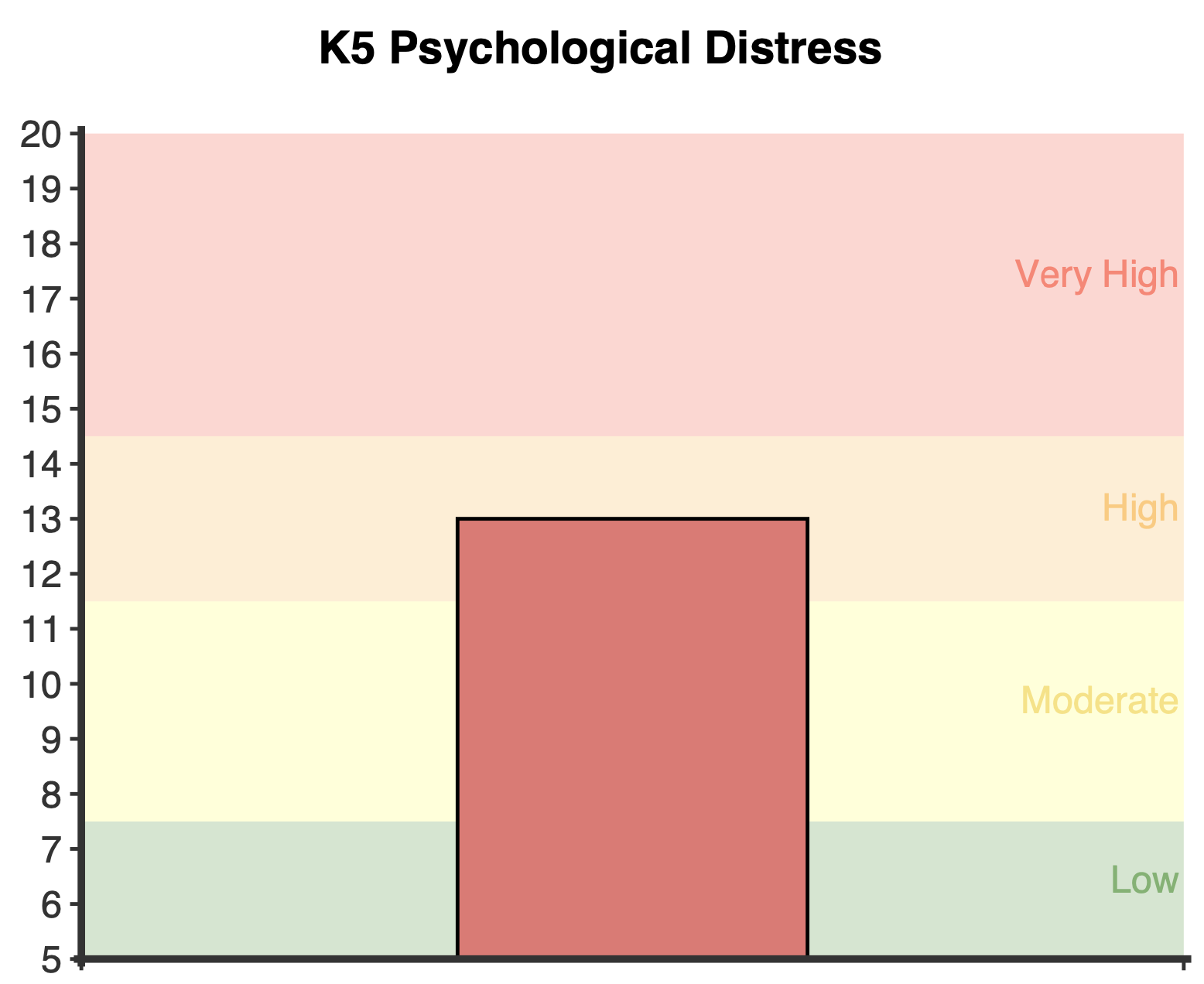

A total score is calculated by summing all items for a possible range of 5 to 25. Higher scores indicate higher levels of psychological distress.

Four categories of psychological distress were outlined by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2009), and include:

A normative percentile is calculated, contextualising the responses in comparison to typical patterns of responding among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Brinkley et al., 2021; Cunningham et al., 2012). For example, a percentile of 50 indicates average (and healthy) levels of distress, while a percentile of 90 indicates the respondent has more distress than 90% of the indigenous population.

A cut off score of 11 and above is indicative of clinically significant psychological distress, such as depression or anxiety symptoms (Brinckley, 2021).

The K5 is derived from the 10-item version developed by Kessler and Mroczek (1992). The 5 item version retains the core elements of the K10 but provides a shorter yet similarly robust measure of psychological distress.

Several studies have assessed the psychometric properties of the K5, supporting various aspects of its validity and reliability. Excellent internal consistency values via Cronbach’s alpha have been reported, ranging from .85 to .89 (Brinckley et al 2021; Kelaher et al 2014; McNamara et al 2014).

Brinckley and colleagues (2021) principal components analysis found 70.1% of variance attributable to a single factor, giving support for a unidimensional structure in line with previous investigations (McNamara et al 2014). McNamara and colleagues (2014) found appropriate patterns of convergent validity and a strong classification agreement between the K-10 and K-5 in low, moderate, high and very high categories (kappa=.87).

Brinkley et al. (2021) collected data from a sample of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders adults (16 years and older, n=6988) as did Cunningham and colleagues (2012;n=5417). Combining both these dataset, NovoPsych calculated percentiles, describe below:

Kessler, R., & Mroczek, D. (1992). An update of the development of mental health screening scales for the US national health interview study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Australian Government Department of Health. (2018). Primary Mental Health Care Minimum Data Set: Scoring the Kessler-5. Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2009). Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Catalogue No.: IHW 24). Canberra, Australia: AIHW.

Brinckley, M. M., Calabria, B., Walker, J., Thurber, K. A., & Lovett, R. (2021). Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of a culturally modified Kessler scale (MK-K5) in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11138-4

Burgess, C. P., Johnston, F. H., Berry, H. L., McDonnell, J., Yibarbuk, D., Gunabarra, C., Mileran, A., & Bailie, R. S. (2009). Healthy country, healthy people: the relationship between Indigenous health status and “caring for country”. The Medical Journal of Australia, 190(10), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02566.x

Cunningham, J., & Paradies, Y. C. (2012). Socio-demographic factors and psychological distress in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian adults aged 18-64 years: analysis of national survey data. BMC Public Health, 12, 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-95

Kessler, R., & Mroczek, D. (1992). An update of the development of mental health screening scales for the US national health interview study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Kelaher, M. A., Ferdinand, A. S., & Paradies, Y. (2014). Experiencing racism in health care: the mental health impacts for Victorian Aboriginal communities. The Medical Journal of Australia, 201(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja13.10503

LaGrappe, D., Massey, L., Kruavit, A., Howarth, T., Lalara, G., Daniels, B., Wunungmurra, J. G., Flavell, K., Barker, R., Flavell, H., & Heraganahally, S. S. (2022). Sleep disorders among Aboriginal Australians with Machado-Joseph Disease: Quantitative results from a multiple methods study to assess the experience of people living with the disease and their caregivers. Neurobiology of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms, 12, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbscr.2022.100075

Martin, K. E., & Wood, L. J. (2017). Drumming to a new beat: A group therapeutic drumming and talking intervention to improve mental health and behaviour of disadvantaged adolescent boys. Children Australia, 42(4), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2017.40

McNamara, B. J., Banks, E., Gubhaju, L., Williamson, A., Joshy, G., Raphael, B., & Eades, S. J. (2014). Measuring psychological distress in older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Australians: a comparison of the K-10 and K-5. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38(6), 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12271

Redman-MacLaren, M. L., Klieve, H., McCalman, J., Russo, S., Rutherford, K., Wenitong, M., & Bainbridge, R. G. (2017). Measuring resilience and risk factors for the psychosocial well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander boarding school students: Pilot baseline study results. Frontiers in Education, 2, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00005

Stolk, Y., Kaplan, I., & Szwarc, J. (2014). Clinical use of the Kessler psychological distress scales with culturally diverse groups. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1426

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved