The Appearance Anxiety Inventory (AAI) is a 10 question self-report scale that measures the cognitive and behavioural aspects of body image anxiety in general, and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) in particular. Appropriate for use with adults and adolescents as young as thirteen, the brief nature of the AAI can provide a quick snapshot of symptom severity to assist in the initial assessment and to monitor treatment progress over time.

The AAI was specifically developed by Veale et al. (2014) to capture typical BDD cognitive processes (e.g., rumination and self-focused attention) and behaviours (e.g., excessive checking or camouflaging, avoidance) that, based on the theoretical model of BDD, arise from the appearance concerns and help maintain BDD symptoms.

Example AAI items:

The AAI has three subscales that represent typical symptom clusters among people with BDD:

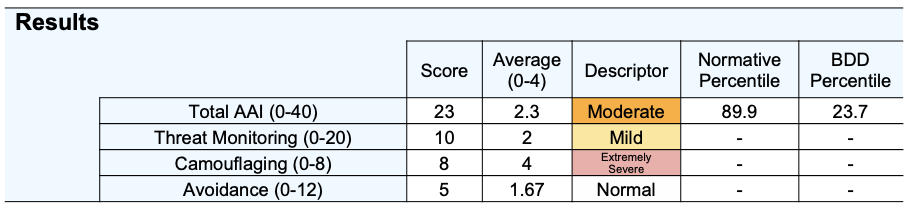

Scores consist of a total raw score (0-40), where a higher score is indicative of more severe appearance anxiety, as well as three subscales.

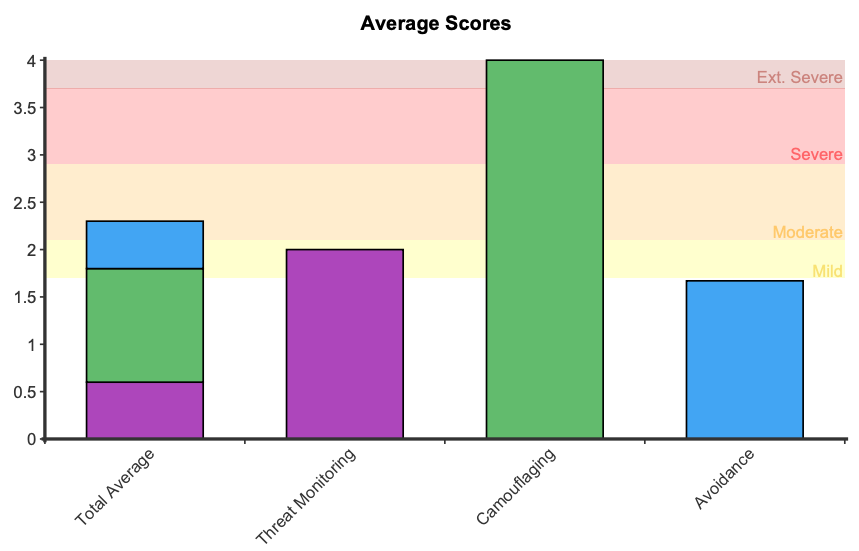

A symptom severity descriptor (e.g. mild, moderate, severe) is provided to describe the level of appearance anxiety. While it is common to experience mild appearance anxiety, moderate levels are of clinical significance and are likely to interfere with daily functioning.

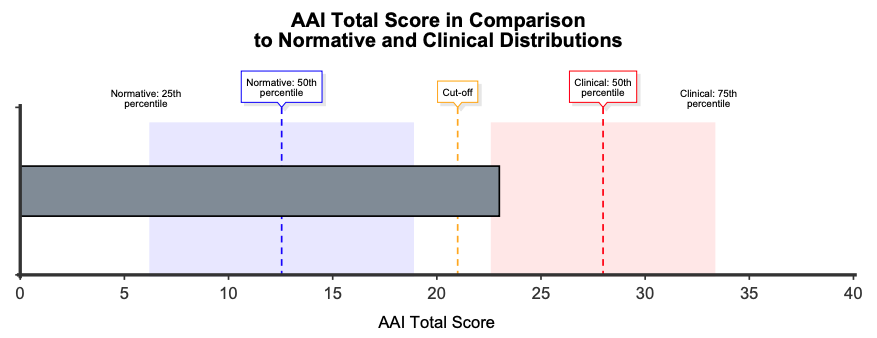

A cutoff score of 21 is indicative of high risk of clinical problems consistent with significant body image anxiety and/or Body Dysmorphic Disorder (Jacobson & Truax, 1991).

Average scores from 0 to 4 are presented, indicating the general level of agreement from “Not at all” to “All the time” on the Likert scale.

The three subscales are:

Two percentiles are presented to indicate how AAI scores compare to a body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) group and a community sample. A BDD percentile of 50 indicates average symptoms for someone with a BDD diagnosis (before receiving treatment), while the community percentile represents scores in comparison to a normal population. For example, a score of 27 represents a BDD percentile of 50 and a normative percentile of 97. This indicates that compared to the normal population the respondent scored higher than 97 percent of individuals, which corresponds to a typical presentation for someone with BDD.

A comparison graph is presented showing where the respondent’s score sits in comparison to the normative and BDD samples, with shaded areas around the means indicating the two middle quartiles (between 25th and 75th percentile). This graph can help contextualise AAI scores in comparison to the distribution of responses among clinical and non-clinical groups. A cutoff score of 21 indicates the point at which symptoms are defined as clinically significant.

Symptom descriptors are also presented for the total score and each of the subscale scores. These descriptors are determined by the distance from the normative mean:

On first administration an average score graph is presented that shows the overall average score and subscales scores.

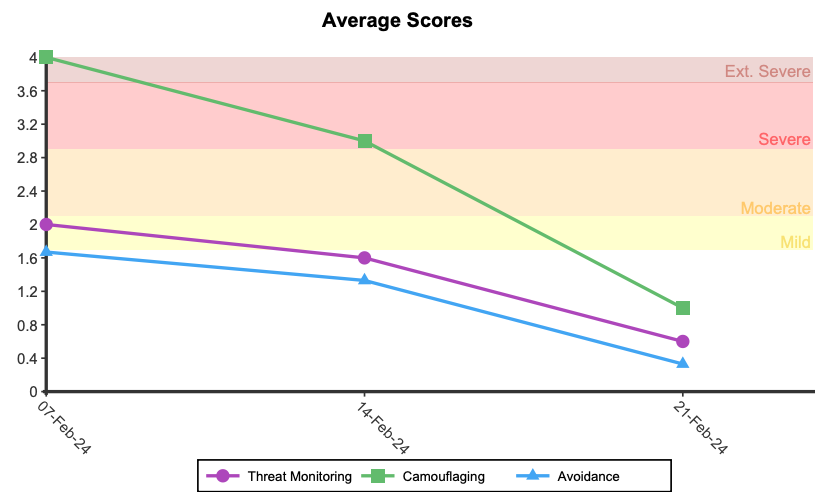

When administered more than once, longitudinal graphs are presented showing change in symptoms over time, including scores presented as Average Scores, a BDD Percentile and a Percentile Rank Compared to Normative Sample.

The AAI was developed by Veale et al (2014) who examined the psychometric properties in a clinical BDD sample and non-clinical community sample in the UK. The AAI was found to have good convergent validity, with correlations of .55 with the clinician rated YBOCS-BDD and .58 with the PHQ9. Internal consistency was high, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.86. The BDD validation sample (n = 139) had a median age of 28 and was 51.8% female. In this sample, two subscales were found using factor analysis: Avoidance and Threat Monitoring.

Gumpert et al. (2024) evaluated the psychometric properties of the AAI among young people referred for BDD treatment (mean age = 15.56), validating its use among this cohort. In contrast to previous research, three factors were identified (Threat Monitoring, Camouflaging and Avoidance). In line with the previous finding, the AAI also demonstrated good sensitivity to change, with scores in the total scale and subscales all significantly decreasing from baseline to post-treatment, supporting its use as an outcome monitoring tool.

The clinical percentiles are calculated from a combination of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) groups from a variety of studies to determine an AAI mean and standard deviation. Hanley et al. (2020) used the AAI in a sample of 71 BDD youth aged between 12 and 25 years where the mean was 26.55 (SD = 6.15). Gumpert et al. (2024) used the AAI in a sample of 182 adolescents with BDD and the mean score was 28.54 (SD = 7.18). Putting the BDD samples together (n = 253), created a combined clinical mean of 27.98 (SD = 6.95). This data can be used to compute clinical percentiles, providing a metric to compare a respondent’s score to people independently diagnosed with BDD.

Similarly, normative percentiles are calculated from a combined sample from a variety of studies. Hanley et al.’s (2020) normative sample (n = 250) had a mean of 12.74 (SD = 7.45) and Roberts (2019) sample of 730 university students (ages 17 – 52; 71% female) had a mean of 12.49 (SD = 8.46). A combined normative sample (n = 980) was calculated, with a a mean of 12.55 (SD = 8.21), providing a metric to compare a respondent’s score to the general population.

The distance from the normative mean was used to produce symptom descriptors:

The cutoff score for the AAI was determined using the normative and clinical distributions combined with formula C as defined by Jacobson & Truax (1991) . The result was a cutoff score of 21. Scores of 21 or above indicate patterns of responding that are consistent with those from someone independently diagnosed with body dysmorphic disorder. Our cut score of 21 used best-practice statistical methods, and was only slightly higher than previous work by Mastro et al. (2016; cutoff score = 20).

Veale, D., Eshkevaria, E., Kanakama, N., Ellisona, N., Costa, A., and Werner, T. (2014). The Appearance Anxiety Inventory: Validation of a Process Measure in the Treatment of Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42, 605-616. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1352465813000556

Gumpert, M., Rautio, D., Monzani, B., Jassi, A., Krebs, G., Fernández de la Cruz, L., Mataix-Cols, D., & Jansson-Fröjmark, M. (2024). Psychometric evaluation of the appearance anxiety inventory in adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2023.2299837

Hanley, S. M., Bhullar, N., & Wootton, B. M. (2020). Development and initial validation of the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Scale for Youth. The Clinical Psychologist, 24(3), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12225

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance : A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/10109-042

Mastro, S., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Webb, H. J., Farrell, L., & Waters, A. (2016). Young adolescents’ appearance anxiety and body dysmorphic symptoms: Social problems, self-perceptions and comorbidities. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 8, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2015.12.001

Roberts, C. L. (2019). Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Adolescents: A New Multidimensional Measure and Associations with Social Risk, Mindfulness, and Self-Compassion [PhD Thesis, Griffith University]. Griffith University Research Repository. https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/551

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved