The Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire-2 (GPSQ-2) is a 14-item self-report measure of gender-related distress (gender dysphoria) in adolescents and adults, and was developed by Bowman et al. (2024).

The GPSQ-2 was developed to assist in assessing outcomes relating to gender-affirming care (medical, surgical, social, or psychological) in transgender and gender-diverse people, the GPSQ-2 revised the original GPSQ (Hakeem et al., 2016) to improve its validity and extend its use to adolescents aged 13 and above (Bowman et al., 2024).

Gender dysphoria can involve significant distress and preoccupation with the mismatch between one’s sex assigned at birth and identified gender, as well as internal variability in how one perceives their gender (Bouman et al., 2016). The GPSQ-2 focuses on two core aspects of gender dysphoria: preoccupation with gender and stability of gender identity:

In clinical practice, GPSQ-2 scores can guide conversations, as high-scores on certain items can help clients articulate specific distresses or goals (e.g., “I see you’ve been very troubled by being prevented from living in your affirmed gender; let’s explore what’s triggering those feelings”). The scale also provides a standardised gauge of gender-related distress, allowing for tracking client progress. Particularly as the scale asks about the past two weeks, it can be repeated at bi-weekly intervals to monitor changes in feelings of dysphoria distress.

Research on the scale has demonstrated meaningful correlations with several psychological constructs such as depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7) and distress (K-10) (Bowman et al., 2024).

Research by Donaghy et al. (2024) demonstrated excellent positive predictive power (99%) with specialist gender clinic diagnosis using the predecessor scale the GPSQ. Given the high correlation between the GPSQ and GPSQ-2 (r = .91), clinicians can have confidence in the GPSQ-2’s ability to identify gender-related distress alongside improved content validity for adolescents.

The GPSQ-2 can assist in formulation and informing treatment by assessing dysphoric thoughts and gender identity variability. For instance, someone with high preoccupation but low instability might have a firmly identified gender but is distressed about barriers to living in that gender role. In contrast, someone with high fluctuation in identity might benefit from exploratory therapy before pursuing medical interventions that may involve lasting changes.

The total score ranges from 0-56 with higher scores indicating more intense experiences of gender dysphoria. Subscale raw scores ranges are listed below:

The GPSQ-2 can be used to screen for gender-related distress, to inform treatment planning, and to monitor changes over time in therapy or after interventions.

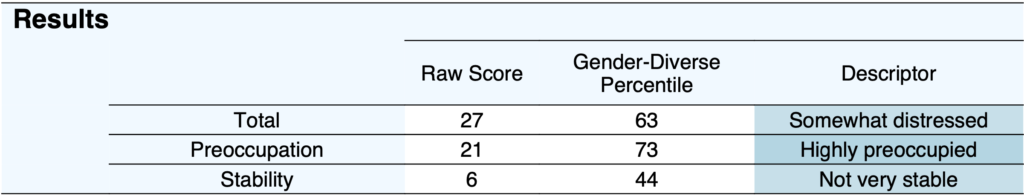

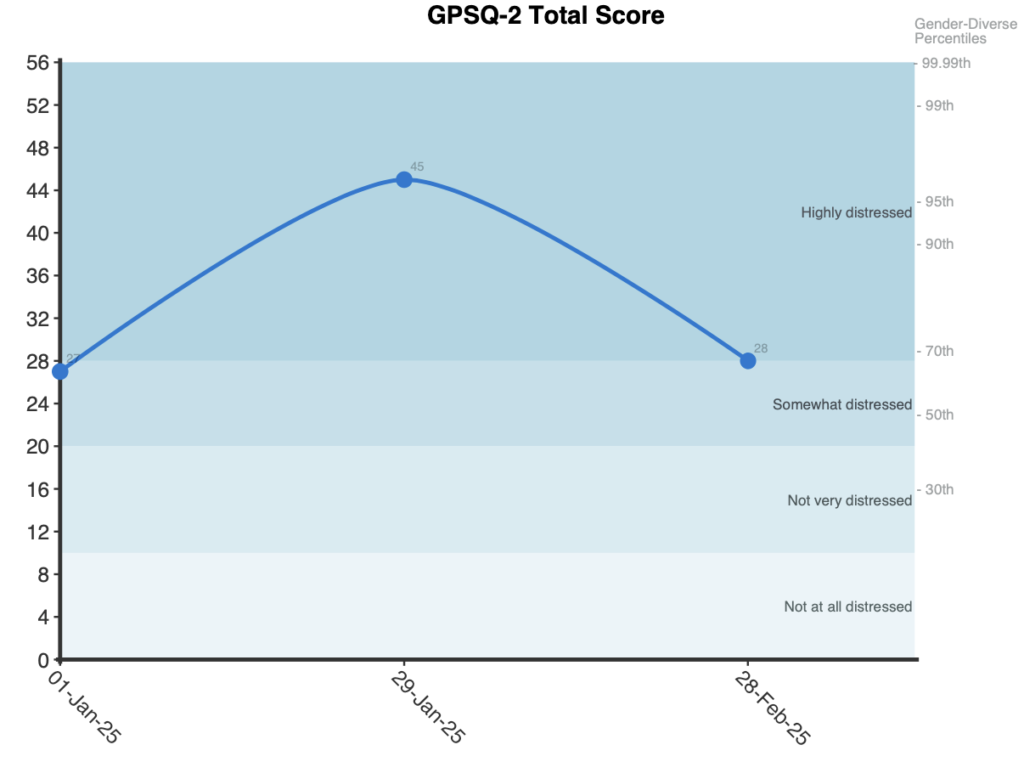

On first administration, a stacked bar graph shows the total and each of the two subscale scores in gender-diverse percentiles. Percentiles give context to a client’s score, showing how they compare to their peers. For example, a percentile of 50 represents the typical level of gender dysphoria distress among members of the gender-diverse community.

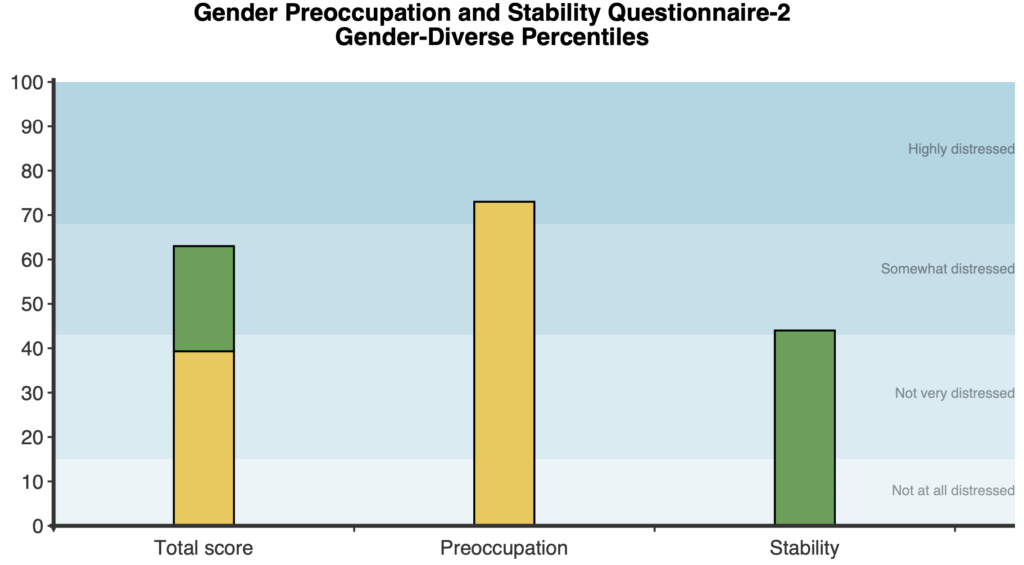

A horizontal comparison graph is also presented showing the respondent’s score in comparison to the cis-gender, gender-diverse and clinical samples.

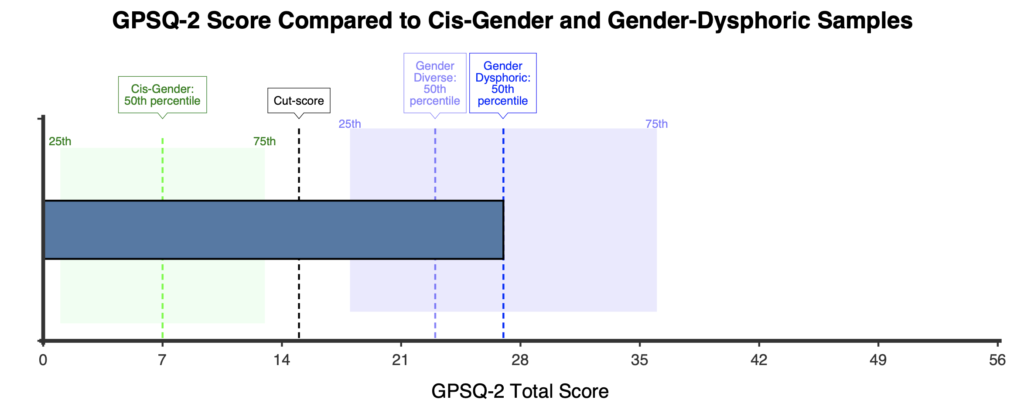

When administered more than once, a line graph is presented for the raw total score with gender-diverse percentile labels on the right.

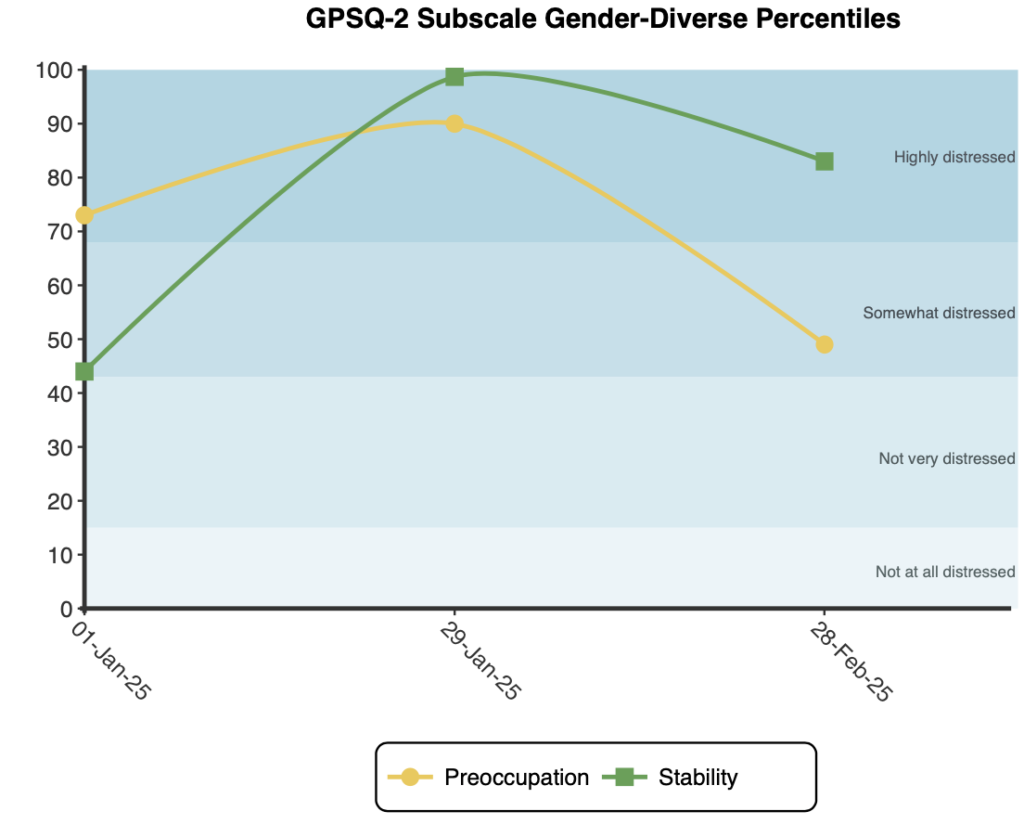

A second line graph is presented plotting each of the two subscales in gender-diverse percentile terms.

Significant changes in the total score are indicated by shifts of half a standard deviation or greater (approximately 6 total score points or more) following the guidelines of the Minimally Important Difference (Turner et al., 2010).

Severity categories for the total and subscales scores were created by Bowman (2022) and adjusted by NovoPsych to align them (total and subscale) based on the percentile distribution of the total score in the gender-diverse sample from Bowman (2024):

The GPSQ-2 demonstrates strong construct validity as a measure of gender-related preoccupation and identity stability. A content validity process involving expert feedback and pilot testing was used to create relevant and understandable items. Empirical tests show high correlations with related measures such as the Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS) and the Gender Identity Reflection and Rumination Scale (GRRS) (Bowman et al., 2024).

Factor analysis indicates that the GPSQ-2 has a two-factor structure corresponding to its theorised subscales: Preoccupation and Stability (Bowman et al., 2024). Bifactor modeling further revealed the two subscales are empirically separable while still being under a dominant general factor. Statistical indices such as McDonald’s omega hierarchical (ω 0.84) and explained common variance indicated that most of the reliable variance in GPSQ-2 scores is accounted for by a general dysphoria factor. In practical terms, the GPSQ-2 can be viewed as primarily unidimensional, while still acknowledging two meaningful sub-dimensions. Thus, clinicians may legitimately use the total score as an overall index of gender dysphoria severity, or examine subscale scores for more nuanced information.

The GPSQ-2 exhibits excellent reliability. Internal consistency is high for the total scale and good for each subscale. In the primary validation sample (n=141), Cronbach’s alpha was α = .92 for the total score, α = .89 for preoccupation, and α = .86 for stability. Test–retest reliability was examined for a subset of participants (n=69) who retook the GPSQ-2 after two weeks. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the total score was high at .88. Subscales showed similar test-retest values (.88 for preoccupation, and .81 for stability).

Normative data have been reported by Bowman et al. (2024) from a gender-diverse community sample recruited from trans and gender-diverse social media sites and support groups (n=141). In this sample, 65% identified as binary (i.e., male/transmale/female/transfemale) and 35% identified as nonbinary/gender-fluid participants (i.e., transgender, non-binary, agender). The authors reported a mean total score of 22.95 (SD = 12.25). Table 1 provides further details including age, subscale means and standard deviations, in addition to further gender-diverse clinical (n=32) and cis-gender community (n=122) norms are also reported by Bowman (2022).

Cut scores were established by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to evaluate the ability of the GPSQ-2 to classify individuals based on their subjective experiences of gender-related distress scores (a 1-item 5-point scale assessing the degree of distress experienced over the previous two weeks relating to gender dysphoria). ROC analysis determined how well the GPSQ-2 could predict different levels of distress as measured by the single item. The total score showed excellent discrimination, with a sensitivity of 97%, and specificity of 87% at a cut-score of 15. The Preoccupation subscale had similar performance (sensitivity = 97%, specificity = 87%) at a cut-score of 13, while the Stability subscale had more moderate classification power (sensitivity = 69%, specificity = 73%) at a cut-score of 3.

Severity categories for the total and subscales are outlined by Bowman (2022), created based on ROC analysis outlined above and a one-way ANOVA test of differences between distress categories (‘not at all distressed’ through to ‘highly distressed’).

Total:

Preoccupation:

Stability:

While the total score and subscale scores have different raw score severity ranges as above, NovoPsych adjusted the ranges to align them based on the percentile distribution of the total score in the gender-diverse sample from Bowman et al. (2024), these new severity ranges work similarly to the above raw score ranges, but allow for the total and subscale scores to be graphed together in gender-diverse percentile terms:

For subscales, NovoPsych adjusted descriptor labels for the two subscales:

Preoccupation:

Stability:

Bowman, S. J., Hakeem, A., Demant, D., McAloon, J., & Wootton, B. M. (2024). Assessing Gender Dysphoria: Development and Validation of the Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire – 2nd Edition (GPSQ-2). Journal of homosexuality, 71(3), 666–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2132440

Bartholomew, E., Smyth, C., Buchanan, B., Baker, S., Hegarty, D. (2025). A Review of the Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire-2 (GPSQ-2): Qualitative Descriptors, Psychometric Properties, and Normative Data.

Bouman, W. P., Claes, L., Brewin, N., Crawford, J. R., Millet, N., Fernandez-Aranda, F., & Arcelus, J. (2016). Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1258352

Bowman, S. J., Hakeem, A., Demant, D., McAloon, J., & Wootton, B. M. (2024). Assessing Gender Dysphoria: Development and Validation of the Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire – 2nd Edition (GPSQ-2). Journal of Homosexuality, 71(3), 666–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2022.2132440

Bowman, S. J. (2022). Assessing gender dysphoria (Doctoral dissertation, University of Technology Sydney). University of Technology Sydney.

Donaghy, O. J. E., Cobham, V., & Lin, A. (2024). Screening adolescent transgender-related distress: Gender preoccupation and stability questionnaire demonstrates excellent criterion validity with multi-disciplinary, pediatric gender specialist assessment. International Journal of Transgender Health. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2024.2378378

Hakeem, A., Črnčec, R., Asghari-Fard, M., Harte, F., & Eapen, V. (2016). Development and validation of a measure for assessing gender dysphoria in adults: The Gender Preoccupation and Stability Questionnaire. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3-4), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1217812

Portney, L. G. (2020). Foundations of clinical research: Applications to evidence-based practice (4th) ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Turner, D., Schünemann, H. J., Griffith, L. E., Beaton, D. E., Griffiths, A. M., Critch, J. N., & Guyatt, G. H. (2010). The minimal detectable change cannot reliably replace the minimal important difference. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.024

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved