The Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) is self-report tool designed to measure various aspects of aggression, encompassing physical and verbal aggression, anger, and hostility.

The Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) is a 29-item self-report instrument designed as a comprehensive measure of aggression in adults (18+) (Buss & Perry, 1992). The BPAQ divides aggression into four related but distinct factors reflected in the subscales below:

The BPAQ can be used to identify aggression-related issues important to a clinical formulation, and is particularly useful as an impartial method of approaching the subject of aggression. It has been used in community and clinical settings, including among criminal offenders, military personnel and students. Moderate associations between Physical Aggression subscale scores and actual violent behaviour have been observed in both clinical and student samples (Diamond & Magaletta, 2006; Tremblay & Ewart, 2005).

It is also useful for monitoring a client’s progress and in evaluating the effectiveness of a particular treatment approach. The scale is commonly used among batteries of measures in correctional service, where the BPAQ can be included pre and post treatment outcome monitoring protocols (CSC, 2009).

When implementing the BPAQ, there are several factors that are useful to consider. Impulsivity, social desirability bias, and cultural differences have all been observed to influence BPAQ scores (Becker, 2007; Harris, 1995; Bryant & Smith, 2001). For example, if a client has known difficulties with impulsivity, a high BPAQ score may overestimate their true aggression level. Furthermore, prominent gender differences in scores have been observed in several investigations, with evidence found for men being higher in general and women being higher in relation to hormonal cycles (Archer & Webb, 2006; Ritter, 2003). Age differences are also apparent, with young people (18-35) displaying higher aggression scores compared to middle age (36-55) and older (55+) groups (Gerevich et al., 2007).

Example BPAQ items:

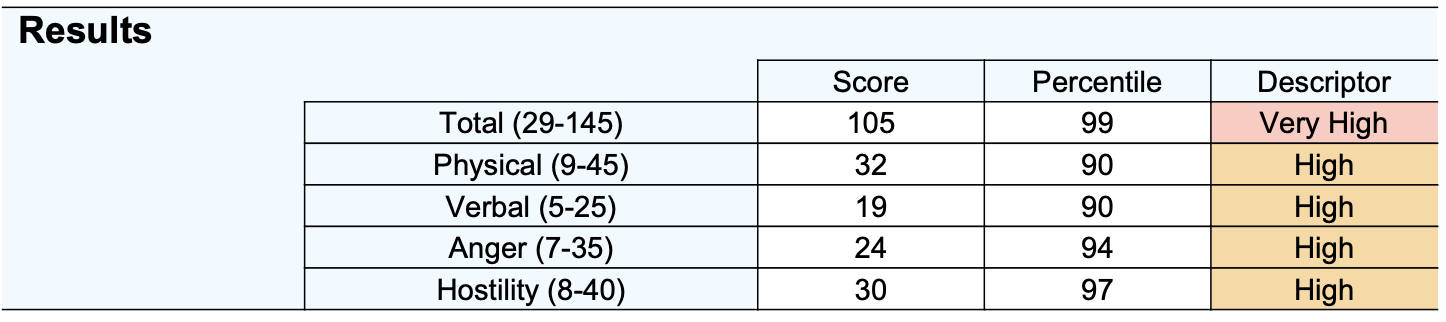

BPAQ scores are presented both as an overall total (range 29 to 149) and at a subscale level.

Higher scores indicate greater endorsement of aggressive statements and indicate a greater propensity for aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Percentiles are presented, indicating the level of aggressiveness in comparison to a gender related normative sample. A percentile of 50 indicates typical (and healthy) levels of aggression, whereas a percentile of 90 indicates aggression in the top 10 percent of men or women (depending on gender). Such high percentiles indicate that aggression likely impacts relationships, personal or professional achievement and overall well-being.

Subscales:

Tendency to engage in physical acts of aggression.

Propensity to engage in verbal arguments and confrontations.

The emotional aspect of aggression, including quick temper and frustration.

Internalised feelings of ill will and suspicion towards others.

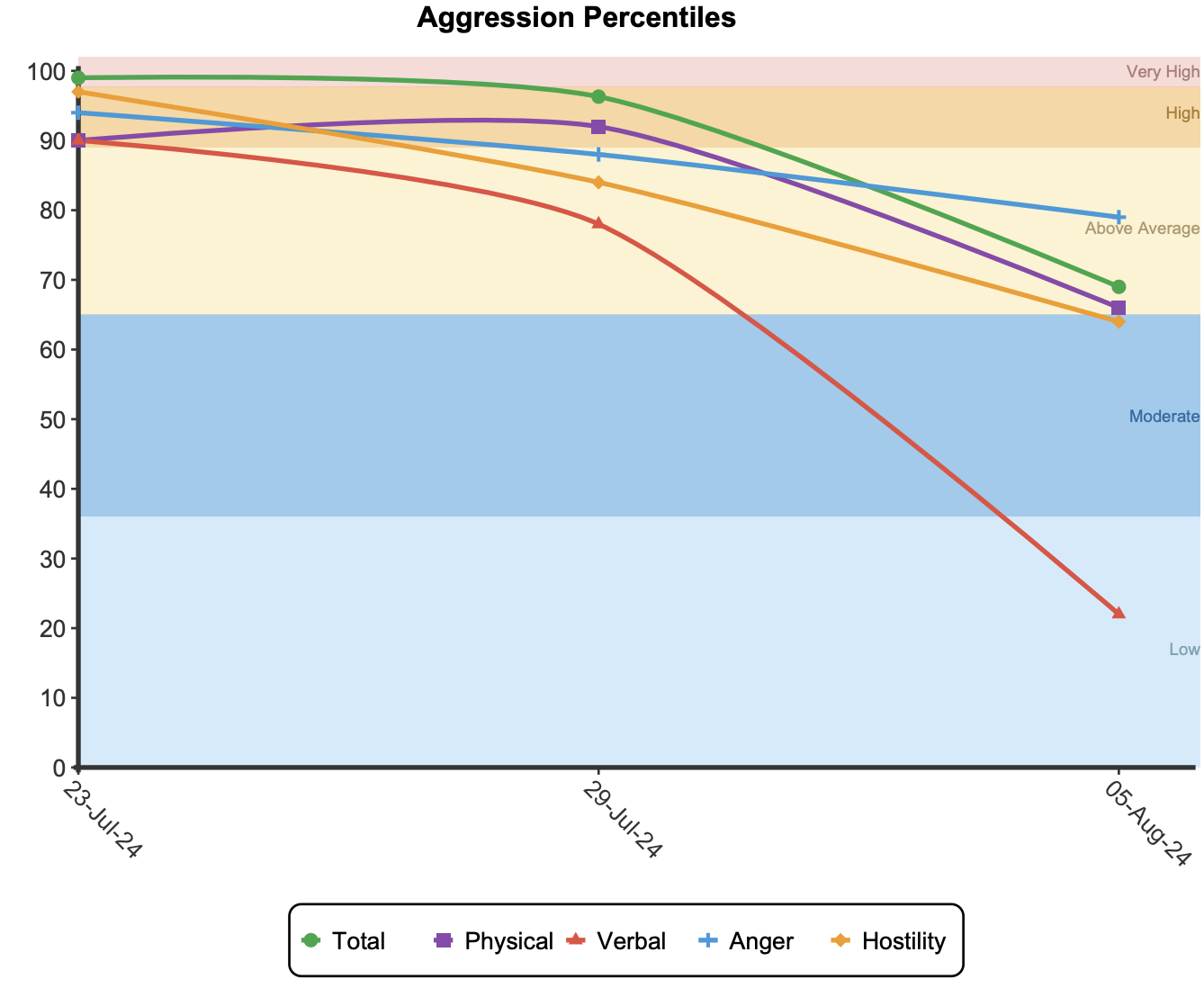

If administered more than once a line graph will be produced for the total and subscale scores.

Aggression can be largely considered pathological, particularly when excessive, inappropriate, and linked to psychological disorders. However aggression is not inherently maladaptive and is heavily reliant on contextual factors (Allen et al., 2018). Anger can propel us to take defensive, bold and vigorous action, so at least some aggression may be adaptive in many contexts.

Findings involving correlations to aggression can provide broader behavioural and emotional insights. For example, aggression, as measured by the BPAQ, has been correlated with increased alcohol intake and trait neuroticism, while being negatively correlated to trait agreeableness (Tremblay & Ewart, 2005). Such findings place scores in a wider context and may suggest a benefit to additional questioning about substance use or interpersonal issues relating to emotional instability. In addition, anger is often considered to be a secondary emotion, whereby an uncomfortable feeling such as sadness is concealed through aggression. Indeed, aggressiveness is correlated with the presence of depression (Rice et al., 2013).

While BPAQ scores are primarily used to assess client aggression levels, identify aggression-related issues and monitor progress, it may also be used as a risk indicator. For example, high responses on items like “Once in a while, I can’t control the urge to strike another person (item 8)” indicates the client may be a risk to themselves and others. The subscales of Physical Aggression and Hostility are of particular note when assessing risk. Archer and colleagues (1995) who observed a significant correlation between BPAQ scores and recent involvement in a violent physical altercation.

Hostility has verified links to poor health outcomes with a particular impact on coronary artery disease and mortality due to all causes (Barefoot & Williams, 2022). People high on hostility have large cardiovascular and endocrine reactions to social provocations. These physiological reactions represent fight-or-flight states accompanied by angry and aggressive responses toward other individuals.

Levels of aggression are related to healthy relational concepts such as assertiveness, whereby people who score extremely low or extremely high on aggressiveness may lack adaptive assertiveness skills. Assertiveness is defined as “the ability to express one’s thoughts and feelings, both positive and negative, in a non-hostile way and without violating the rights of others” (Ollendick, 1983), while aggression involves violent, harmful actions or intentions towards others (Deluty, 1979). While aggression and assertiveness differ conceptually, it is important to acknowledge that they can often overlap in practice, especially in relation to Verbal Aggression (Ostrov et al., 2006). Assertive behaviours can be misinterpreted as aggressive due to their shared goal of exerting control or influence (Dirks et al., 2011; Ostrov et al., 2006). Consequently, very low levels of Verbal Aggression, as measured by the BPAQ, may also be associated with interpersonal difficulties. This is because extremely low Verbal Aggression scores may reflect the absence of assertive behaviours which are necessary for healthy social interactions. When considered along a continuum within the framework of assertiveness skills training, for example, extremely low levels of Verbal Aggression may be reflective of a passive communication style. As such, scoring one (out of five) on the item: ‘I tell my friends openly when I disagree with them’ (Item 4), may indicate a lack of assertiveness that is detrimental to healthy inter-relational dynamics.

The BPAQ was developed to update the earlier Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957), and has been validated in university student samples, community adults, military personnel, and criminal offenders (Gerevich et al., 2007; Gallagher & Ashford, 2016; Pettersen et al., 2018). Validations have spanned several nations including the United States (Buss & Perry, 1992), United Kingdom (Bryant & Smith, 2001), Germany (von Collani & Werner, 2005), Greece (Vitoratou et al., 2009), Italy (Fossati et al., 2003), China (Maxwell, 2007), Portugal (Cunha et al., 2022), Hungary (Zimonyi et al., 2021) and others.

Numerous studies have assessed the factor structure of the BPAQ since the original four factor structure was identified in Buss and Perry’s foundational work (1992). Factor analytic studies by Bernstein & Gesn (1997), Harris (1995), McKay and colleagues (2016) and Pettersen et al., (2018) supported the four-factor structure proposed by Buss and Perry (RMSEA values ranging from .06-.07). Samples ranged in size from 271-1200 and included a diverse range of respondents such as university students from the United States and Canada, general adults from Hungary and violent offenders from Canada.

Adequate to strong internal consistency has been observed for the total scale as well as all four subscales (Archer & Webb, 2006; Bernstein & Gesn, 1997; Buss & Perry, 1992; Gallagher & Ashford, 2016; Gerevich et al., 2007; Harris, 1995; McKay et al., 2016; Pettersen et al., 2018; Tremblay & Ewart, 2005). See table 1 of the supplementary materials.

The BPAQ has demonstrated appropriate patterns of convergent validity across all four subscales. For example, moderate associations between Physical Aggression subscale scores and violent behaviour have been observed in both clinical and student samples. This subscale also correlates (r = .69) significantly with Aggressiveness scores on the Personality Assessment Inventory (Diamond & Magaletta, 2006; Tremblay & Ewart, 2005).

Verbal Aggression, Anger, and Hostility subscales display similar appropriate patterns of convergent validity in both clinical and non-clinical samples (see Diamond & Magaletta, 2006 and Tremblay & Ewart, 2005 for more detail).

Normative data is available for both clinical and non-clinical samples. For instance, Pettersen and colleagues (2018) reported data on violent offenders incarcerated in Canada, while Bernstien & Gesn (1997) used a university student sample. Further details on these samples can be found in table 2 of the supplementary materials. The average total score for a violent male offender is 82, which corresponds to a non-clinical percentile of 78 for males and 93 for females. This means that the average violent offender is more aggressive than 78% of males, and 93% of females.

Weighted means and pooled standard deviations for male and female non-clinical samples were used to construct the percentile tables included in the supplementary materials. As no total was available from Bernstein & Gesn (1997), no weighted means or pooled standard deviations were calculated and instead Tremblay & Ewart’s (2005) total male and female scores were used.

In determining a total cut-off score, we utilised the Jacobson and Truax (1991) method. This involves calculating a cutoff using a formula which considers the standard deviation (SD) and mean (M) of the community and clinical samples. A raw score of 76 was established to distinguish between normal and elevated levels of aggression.

Severity ranges were defined in raw score terms by considering both the cut-off and the distribution of men’s scores being higher relative to women. By using raw scores instead of gender-based percentiles, fewer women are classified in the higher aggression categories—reflective of the higher distribution of male aggression.

Low: 29-61

Average: 62-76

Above Average: 77-89

High: 90-100

Very High: 101-149

Below are tables detailing Cronbach’s alpha values for the total scale and subscales, as well as sample description and percentile tables.

Table 1. Reliability Values Across Studies.

Table 2. Sample Description.

Table 3. Percentile tables for Total and Subscale scores.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

Archer, J., & Webb, I. A. (2006). The relation between scores on the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire and aggressive acts, impulsiveness, competitiveness, dominance, and sexual jealousy. Aggressive Behavior, 32(5), 464-473. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:5<325::AID-AB2480210503>3.0.CO;2-R

Archer, J., Holloway, R., & McLoughlin, K. (1995). Self-reported physical aggression among young men. Aggressive Behavior, 21(5), 325-342. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:5%3C325::AID-AB2480210503%3E3.0.CO;2-R

Abd-El-Fattah, S. (2007). Is the Aggression Questionnaire bias free? A Rasch analysis. International Education Journal, 8(2), 237-248.

Allen, J. J., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). The General Aggression Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.034

Barefoot, J.C., Williams, R.B. (2022). Hostility and Health. In: Waldstein, S.R., Kop, W.J., Suarez, E.C., Lovallo, W.R., Katzel, L.I. (eds) Handbook of Cardiovascular Behavioral Medicine. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85960-6_20

Bernstein, I. H., & Gesn, P. R. (1997). On the dimensionality of the Buss/Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Behavior Research and Therapy, 35(6), 563-568. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00014-4

Bryant, F. B., & Smith, B. D. (2001). Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(2), 138-167. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

Becker, G. (2007). The Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire: Some unfinished business. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(2), 434-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.05.004

Correctional Service of Canada. (2009). Reintegration programs: Violence prevention program. Ottawa, Ontario.

Cunha, O., Peixoto, M., Cruz, A. R., & Gonçalves, R. A. (2022). Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire: Factor structure and measurement invariance among Portuguese male perpetrators of intimate Partner violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 49(3), 451-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548211050113

Dirks, M. A., Treat, T. A., & Weersing, V. R. (2011). The latent structure of youth responses to peer provocation. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(1), 58-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-010-9206-5

Deluty, R. H. (1979). Children’s action tendency scale: A self-report measure of aggressiveness, assertiveness, and submissiveness in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 1061-1071.

Diamond, P. M., & Magaletta, P. R. (2006). The Short-Form Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ-SF): A validation study with federal offenders. Assessment, 13, 227-240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191106287666

Fossati, A., Maffei, C., Acquarini, E., & Di Ceglie, A. (2003). Multigroup confirmatory component and factor analyses of the Italian version of the Aggression Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 54-65. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.19.1.54

Gerevich, J., Bácskai, E., & Czobor, P. (2007). The generalizability of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 16(3), 124-136. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.221

Gallagher, J. M., & Ashford, J. B. (2016). Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire: Testing alternative measurement models with assaultive misdemeanor offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(11), 1639-1652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816643986

Harris J. A. (1995). Confirmatory factor analysis of The Aggression Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(8), 991-993. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(95)00038-y

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12-19. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12

Maxwell J. P. (2007). Development and preliminary validation of a Chinese version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire in a population of Hong Kong Chinese. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(3), 284-294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701317004

McKay, M. T., Perry, J. L., & Harvey, S. A. (2016). The factorial validity and reliability of three versions of the Aggression Questionnaire using Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 12-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.028

Rice, S. M., Fallon, B. J., Aucote, H. M., & Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2013). Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: Furthering the assessment of depression in men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(3), 950-958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.013

Tremblay, P. F., & Ewart, L. A. (2005). The Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire and its relations to values, the Big Five, provoking hypothetical situations, alcohol consumption patterns, and alcohol expectancies. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(2), 337-346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.012

Kiewitz, C., & Weaver, J. B. III. (2007). The aggression questionnaire. In R. A. Reynolds, R. Woods, & J. D. Baker (Eds.), Handbook of research on electronic surveys and measurements (pp. 343–347). Idea Group Reference/IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59140-792-8.ch047

Ostrov, J. M., Pilat, M. M., & Crick, N. R. (2006). Assertion strategies and aggression during early childhood: A short-term longitudinal study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(4), 403-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.10.001

Ollendick, T. H. (1983). Development and validation of the children’s assertiveness inventory. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 5, 1-15.

Ritter, D. (2003). Effects of menstrual cycle phase on reporting levels of aggression using the Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29(6), 531-538. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10054

Vitoratou, S., Ntzoufras, I., Smyrnis, N., & Stefanis, N. C. (2009). Factorial composition of the Aggression Questionnaire: A multi-sample study in Greek adults. Psychiatry Research, 168(1), 32-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.016

von Collani, G., & Werner, R. (2005). Self-related and motivational constructs as determinants of aggression. An analysis and validation of a German version of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1631-1643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.027

Zimonyi, S., Kasos, K., Halmai, Z., Csirmaz, L., Stadler, H., Rózsa, S., Szekely, A., & Kotyuk, E. (2021). Hungarian validation of the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire-Is the short form more adequate?. Brain and Behavior, 11(5), e02043. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2043

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved