Hegarty, D., Buchanan, B. ( 2021, June 25). The Value of NovoPsych Data – New Norms for the Brief-COPE. NovoPsych

As NovoPsych has a lot of clinical data for a wide variety of psychological tests we are beginning to use this data to develop our own clinical norms. We believe there is added benefit in using this data for clinical norms as we have large sample sizes that are generally larger than what the tests were originally normed on. There is also the added benefit that the norms are then a good reality of what clinicians are seeing in their day-to-day practice.

In this article we discuss how we created norms for one the assessments in NovoPsych, the Brief COPE.

To use this valuable real-world data it is important that we engage in thorough “data tidying” to ensure the picture we are getting isn’t distorted. We’ve developed algorithms to exclude non-valid data, for example picking up on when a clinician might be testing out a scale by entering all responses with the minimum values, the maximum values, or just playing around by entering different values. We can use the time taken to complete the test where we are assuming that when tests are completed either too quickly or too slowly (when compared to the norm) they might be ‘practice’ data. Thankfully given our large dataset we can afford to err on the side of caution and remove lots of potentially dubious data.

Brief COPE Data Analysis for Norming

One of the most searched scales on NovoPsych is the Brief COPE, but despite its popularity there are actually no high quality norms available for the scale. Therefore we have gone about creating our own clinical norms. We have gathered the data from the Brief COPE from between 8 October 2018 and 22 March 2021 which resulted in 4512 completed samples.

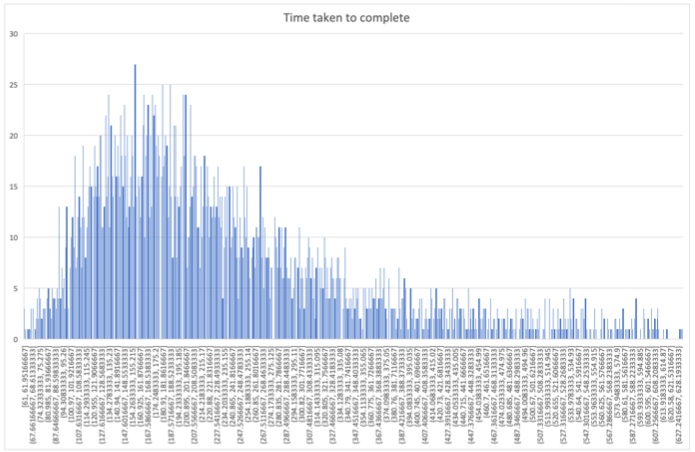

To clean the data we used time taken to complete the assessment and found it was heavily right-skewed with a lot of participants taking a great length of time to complete the assessment (up to 21 hours). Data that took significantly longer (> 3 S.D.) than the mean (342 seconds) to complete were considered outliers and were removed. After data removal the maximum time for completion was 632 seconds – this seems a reasonable amount of time to complete the 28 items (at an average of 22.5 seconds per response). Responses that took 60 seconds or less to complete were also removed as it was thought that this was too quick for someone to complete the assessment properly.

There was a small number of data entries (n = 47) where there was missing data for the individual items in the survey, so these items were removed. Data was removed where the respondent indicated that they were not using any coping strategies at all (i.e. a total raw score of 28) as it was thought that these were more likely to be ‘dummy’ or practice responses. We also removed data where the client name was either “dummy client”, “test”, “patient”, “generic”, as these might be dummy responses. It is recognised that some of these could be legitimate responses, however it was thought that it was best to remove all of these to be sure.

As a final step, the raw total score was used to determine other possible outlier responses by removing data that was +/- 3 S.D.s from the mean.

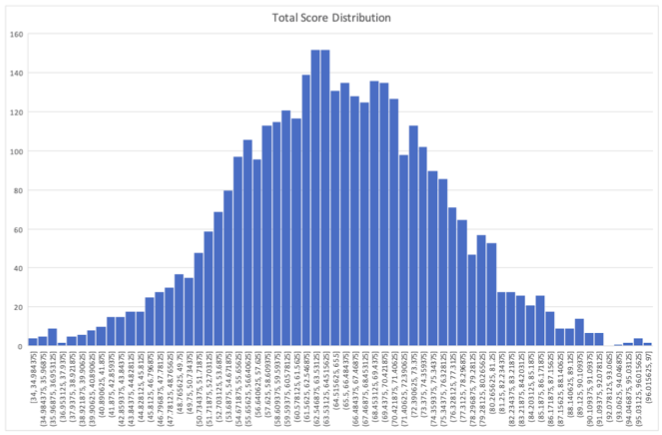

As a result of this data tidying there were 877 responses removed and the final sample size for the NovoPsych Brief COPE clinical data was 3635. This final data presented as an approximate normal distribution for the total scores (see Figure 1), although the time taken to complete data was still right-skewed (see Figure 2).

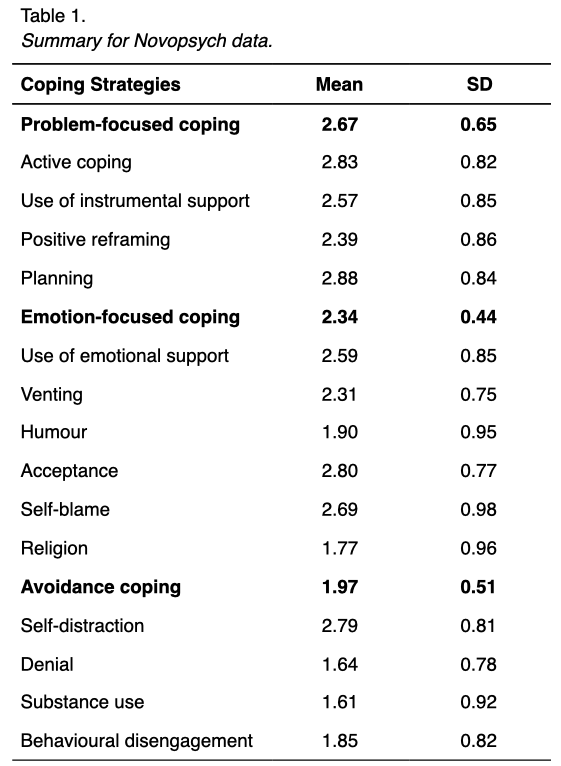

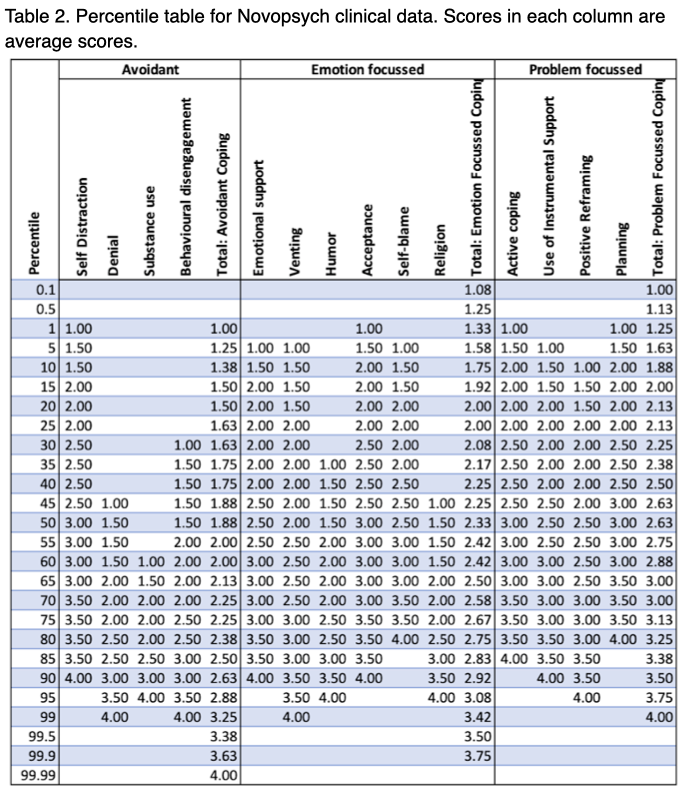

As a result of this process, we can now present the means and standard deviations for each subscale of the NovoPsych Brief COPE clinical data (see Table 1).

We also developed a percentile table for all subscales and coping scales (see Table 2). This was developed by ordering each subscale and coping scale in ascending order and then calculating the score that would occur at the appropriate percentile. It can be seen in Table 2 that some of the subscales are quite skewed. This makes sense given these subscales are derived from only two questions within the Brief COPE. It also makes sense that the coping scales appear to be more uniformly distributed as they are made up of between 8 (avoidant & problem focussed) and 12 (emotion focussed) questions.

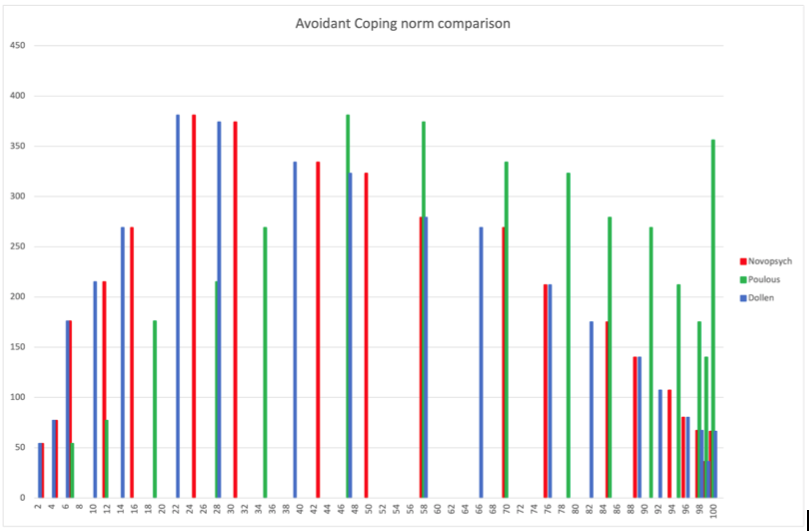

As part of this process we also looked for some good normative data that we could use to compare results to. We found two suitable options: Dollen et al. (2015) and Poulus et al. (2020). The Dollen et al. (2015) data was obtained from 62 Australian and Dutch athletes and the Poulus et al. (2020) data was obtained from 316 esports athletes. The Poulus et al. (2020) data was presented in much more detail with means and standard deviations presented for all sub-scales of the Brief COPE, whereas the Dollen et al. (2015) data was only presented for coping scales.

When comparing the normative data to the clinical data using frequency histograms for the coping scales, we found that the Dollen et al. (2015) data presented much like the NovoPsych clinical data, whereas we found the Poulous et al. (2020) data presented more like what might be expected of normative data. For example, as seen in Figure 3, if we used our clinical raw data but calculated percentiles using the mean and standard deviation of the Poulous et al. (2020) sample for Avoidant Coping, we found that a lot of our data was left-skewed – as might be expected. Conversely, the Dollen et al. (2015) data looked similar to the clinical data. Therefore, based upon the results observed in our frequency histograms, it appeared as if the Poulous et al. (2020) data would be the most appropriate to use for our normative data.

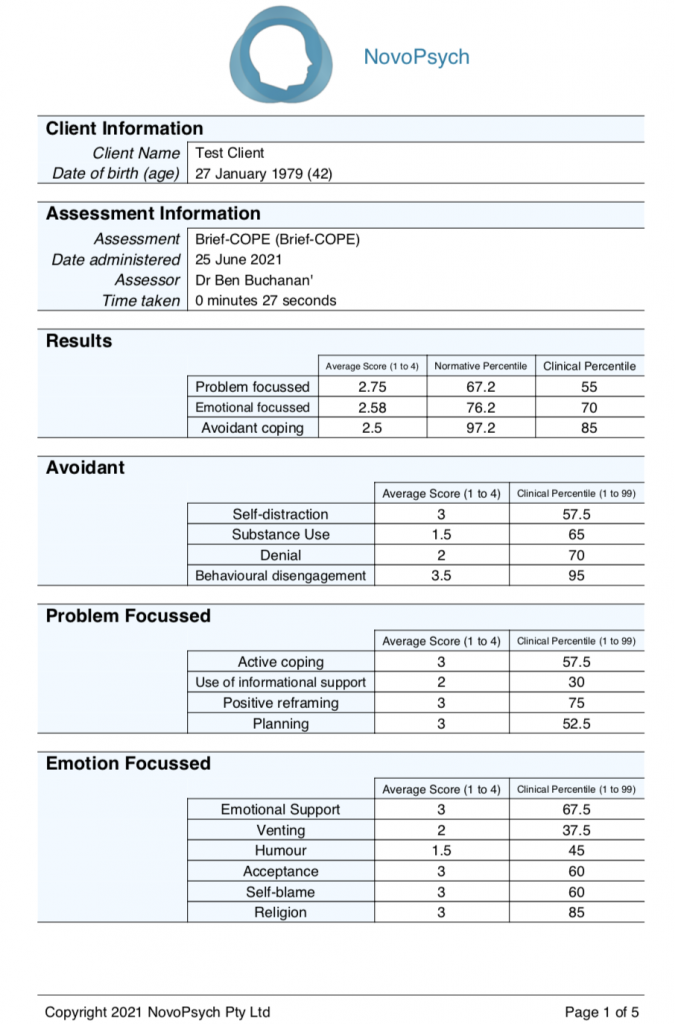

All this analysis and data is synthesized and presented when a NovoPsych user administer the Brief COPE to a client.

References:

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol is too long: Consider the brief cope. International journal of behavioral medicine, 4(1), 92-100.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology, 56(2), 267.

Dias, C., Cruz, J. F., and Fonseca, A. M. (2012). The relationship between multidimensional competitive anxiety, cognitive threat appraisal, and coping strategies: A multi-sport study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol.10, 52–65. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2012.645131

Eisenberg, S. A., Shen, B. J., Schwarz, E. R., & Mallon, S. (2012). Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. Journal of behavioral medicine, 35(3), 253-261.

Poulus, D., Coulter, T. J., Trotter, M. G., & Polman, R. (2020). Stress and Coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00628

Eisenberg, S. A., Shen, B. J., Schwarz, E. R., & Mallon, S. (2012). Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. Journal of behavioral medicine, 35(3), 253-261.