The Empathy Quotient – 40 item version (EQ-40) is a self-report tool to assess empathy in adults (18 years of age and older). The EQ-40 (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004) assesses various aspects of empathy and three subscales are included:

Empathy is a crucial component of social cognition and plays a significant role in interpersonal relationships, mental health, and overall well-being (Decety & Ickes, 2009). On average, women have significantly higher levels of empathy compared with men.

Low empathy is a transdiagnostic signal of possible interpersonal difficulties, and has been associated with diverse psychological conditions, such as autism, ADHD and personality disorders (Dinsdale & Crepi, 2013; Groen et al., 2018; Michaels et al., 2014; Rum & Perry, 2020; Schwenk et al., 2011; Turner et al., 2019).

The scale is often used as part of an assessment for Autism, helping clinicians gain insight into the individual’s social functioning and potential challenges they may face in their relationships. However, note that the EQ-40 measures a particular aspect or understanding of empathy. Therefore, it cannot measure the entirety of empathy given the development of a consensus on the definition of empathy, types of empathy, and how it is experienced remains the subject of ongoing research (Eklund & Meranius, 2021).

While low levels of empathy may impede many aspects of relationships, extremely high levels of empathy can contribute to a cascade of various negative emotional responses and psychological difficulties. This is because heightened empathic tendencies may result in personal distress and excessive guilt, which in turn increase the likelihood of internalising problems such as fear/arousal symptoms and anhedonia/misery symptoms (Tone & Tully, 2014). These internalising problems are influenced by factors including genetic predispositions towards physiological hyper-arousal and unhelpful thought processes, as well as environmental factors like maladaptive parenting (Tone & Tully, 2014).

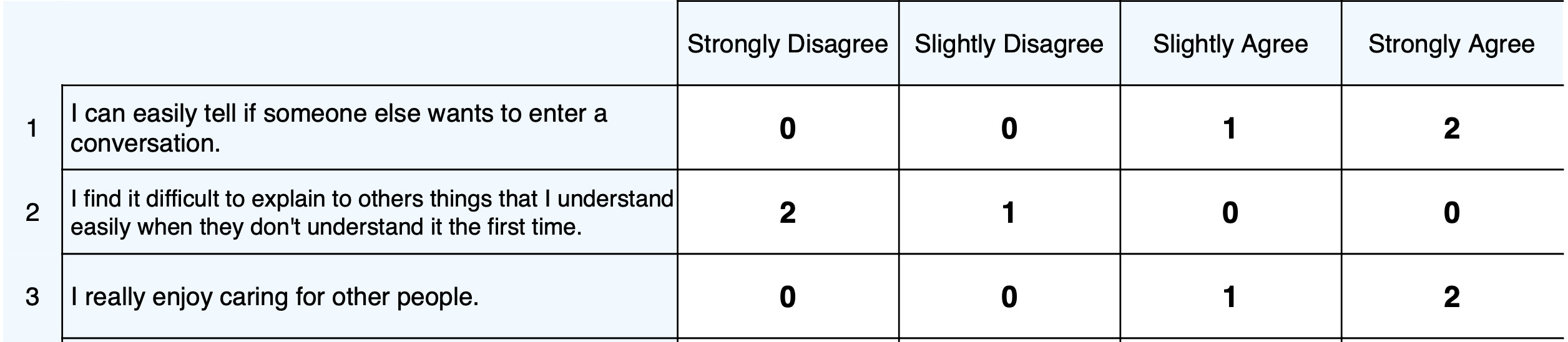

Example EQ-40 items:

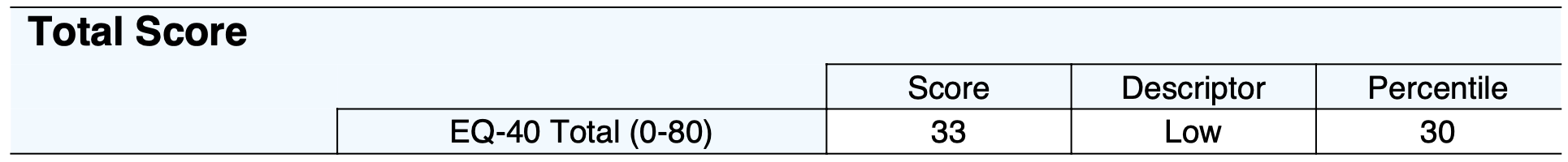

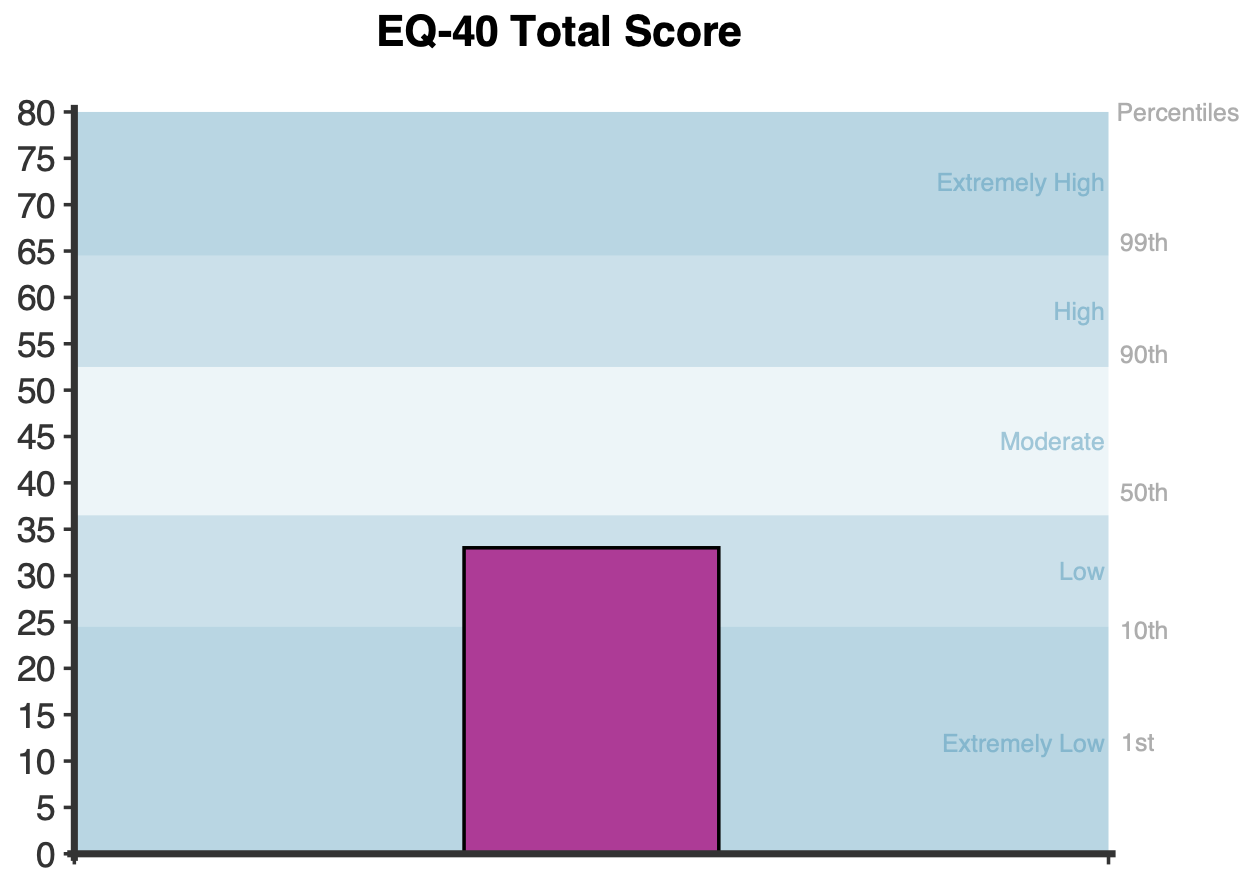

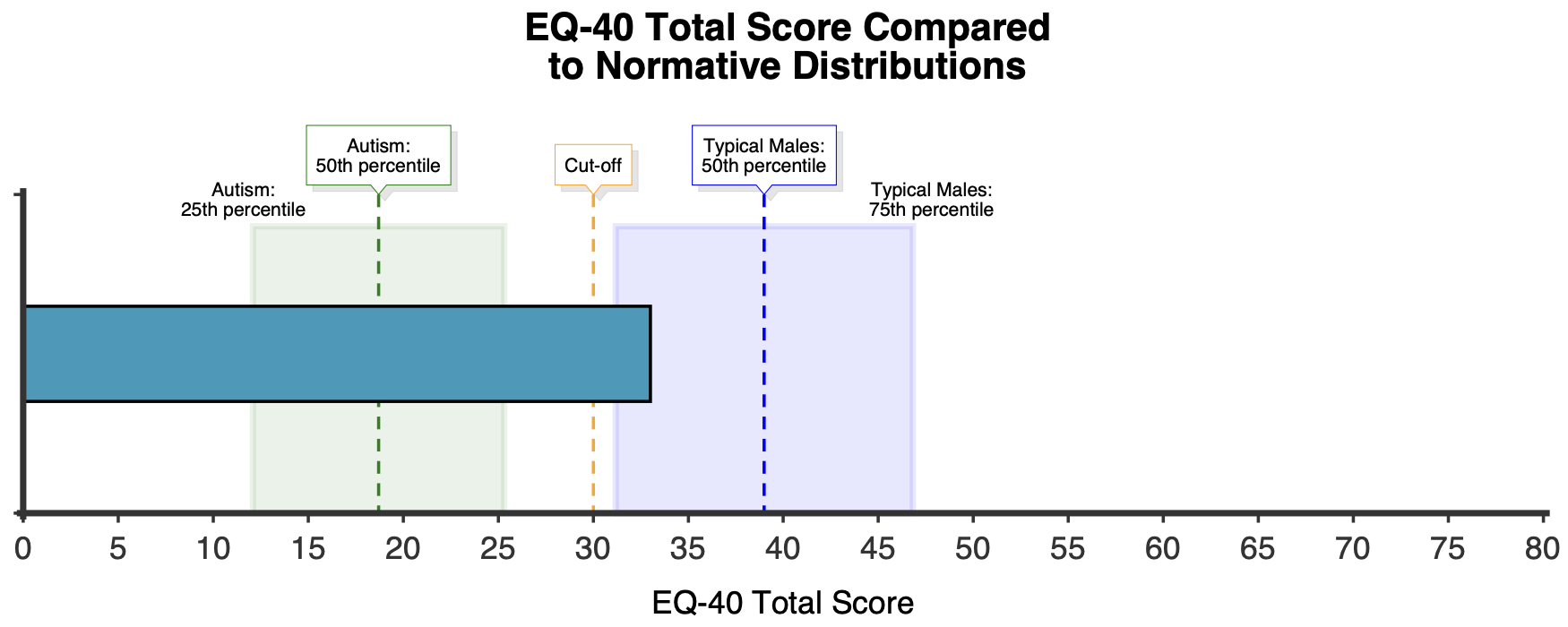

The EQ-40 yields a total score between 0 and 80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of empathy (Baren-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004). The client’s score is also converted to a percentile based on normative data for their gender, providing useful information about the client’s level of empathy relative to individuals of the same gender. While the percentile is gender-specific, the overall descriptor is gender-neutral.

A graph comparing the client’s total score to the normative distributions for gender matched non-clinical (neurotypical) and clinical (autism) samples is presented, with shaded areas around the means demarcating the two middle quartiles between the 25th and 75th percentile. This graph contextualises the client’s score relative to the distribution of scores among neurotypical and autism samples.

Interpretation of EQ-40 scores should consider that females typically score significantly higher than males, making it important to refer to the client’s gender-specific percentile. A consequence of these gender differences is that men are seven times more likely to be described as having “Extremely Low Empathy” compared to women (i.e., 5% of men and 0.7% of women are in the extremely low category).

A cut-off score of 30 is the threshold at which Baren-Cohen & Wheelwright (2004) suggest that the EQ-40 can be used to discriminate between neurotypical and autistic individuals. About 80% of adults with autism score at or below this cut-off, while only 12% of neurotypical adults do.

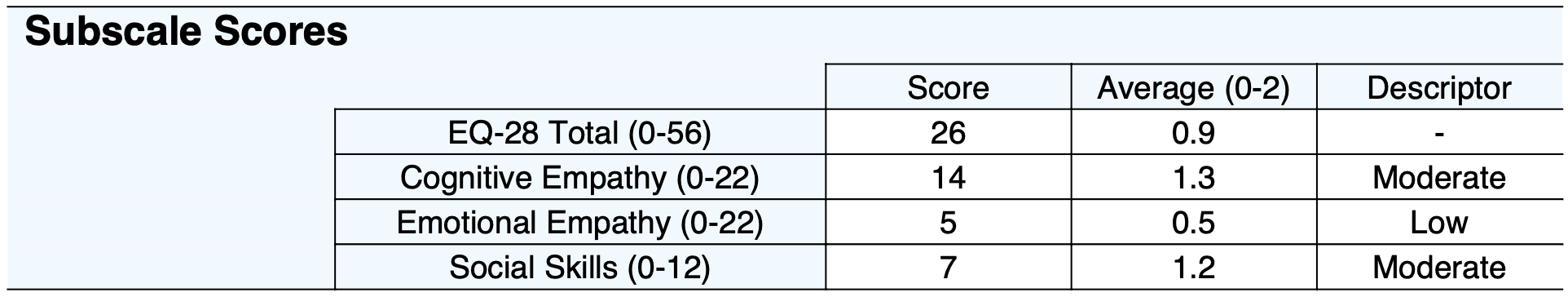

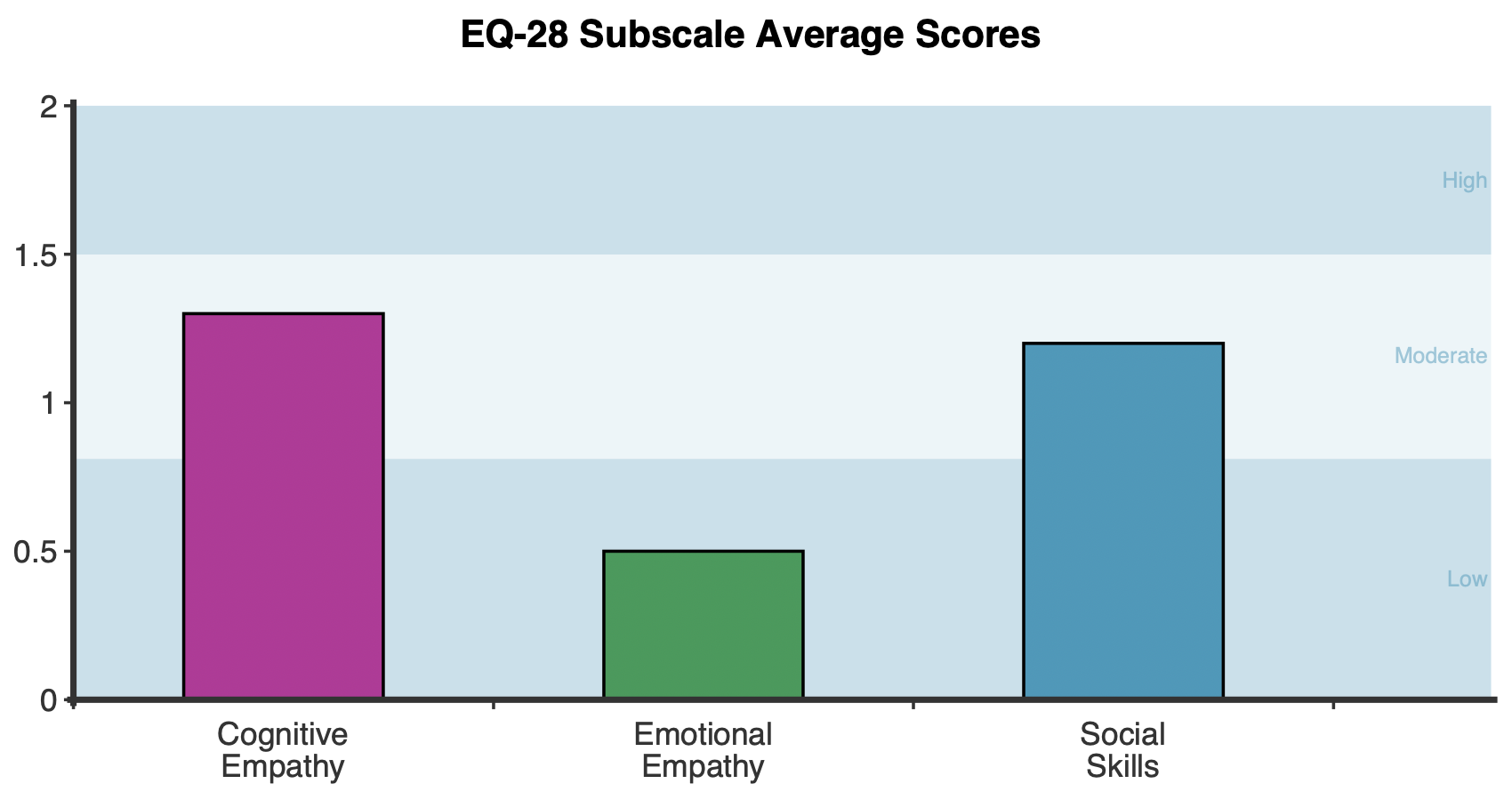

In addition to presenting scores for the EQ-40, scores for the shortened 28-item version of the Empathy Quotient (EQ-28) are presented. The EQ-28 results are presented as average scores, which represent the typical score for each item (between 0 and 2). The EQ-28 includes three subscales:

EQ-28 subscale scores are categorised as Low, Moderate, or High. Low scores are defined as average scores of 0.81 or lower, which corresponds to being lower than approximately the 15th percentile compared to a combined sample of males and females (Groen et al., 2015). Given the gender differences, men are disproportionately more likely to be described as having low empathy. Average scores of 1.5 or higher are categorised as High and correspond to approximately the 85th percentile.

The EQ-40 is a shortened version of the EQ which originally contained 60 items, including 20 filler items. The EQ-40 does not contain any of the filler items and simply retains all items relating to empathy (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

The EQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Lawrence et al., 2004; Allison et al., 2011). A meta-analysis examining the convergent validity of the EQ found moderate positive correlations between the EQ and comparable measures like the Interpersonal Reactivity Index and self-assessed empathising (de Lima & Osório, 2021). Given its ability to discriminate between empathy and these related constructs, the EQ appears to have adequate divergent validity (de Lima & Osório, 2021; Wheelwright et al., 2006). Test-retest reliability for the EQ is excellent (r =.97; Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004).

Neurotypical adults (i.e., adults without ADHD or Autism) typically score higher on measures of empathy than those with Autism. Females typically score higher than males. Normative data for EQ-40 total scores from research conducted by Wheelwright and colleagues (2006) are as follows, and form the basis of computed percentiles.

Non-clinical (Neurotypical)

Clinical (Autism)

The scoring approach uses qualitative descriptors to categorise the total scores. Each qualitative descriptor corresponds to a specific range of total scores. The ranges for these descriptors were determined using percentiles derived from a normative non-clinical (neurotypical) sample of 1,761 males and females obtained from a study by Wheelwright and colleagues (2006).

While the EQ-40 does not include subscales, the 28-item version (EQ-28) has three subscales, with the following means and standard deviations for 685 adults reported by Groen and colleagues (2015):

EQ-28 Total

Cognitive Empathy

Emotional Empathy

Social Skills

Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(2), 163–175.

Allison, C., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S. J., Stone, M. H., & Muncer, S. J. (2011). Psychometric analysis of the Empathy Quotient (EQ). Personality and Individual Differences, 51(7), 829–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.005

Bons, D., van den Broek, E., Scheepers, F., Herpers, P., Rommelse, N., & Buitelaaar, J. K. (2013). Motor, emotional, and cognitive empathy in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 425-443. Doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9689-5

Decety, J., & Ickes, W. (Eds.). (2009). The social neuroscience of empathy. MIT Press.

de Lima, F. F., & Osório, F. de L. (2021). Empathy: Assessment Instruments and Psychometric Quality – A Systematic Literature Review With a Meta-Analysis of the Past Ten Years. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 781346–781346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781346

Dinsdale, N., & Crespi, B. J. (2013). The Borderline Empathy Paradox: Evidence And Conceptual Models For Empathic Enhancements In Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal Of Personality Disorders, 27(2), 172–195. https://Doi.Org/10.1521/Pedi_2012_26_071

Eklund, J. H., & Meranius, M. S. (2021). Toward a consensus on the nature of empathy: A review of reviews. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.022

Groen, Y., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Den Heijer, A. E., Tucha, O., & Althaus, M. (2015). The Empathy and Systemising Quotient: The Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Version and a Review of the Cross-Cultural Stability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 2848–2864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2448-z

Lawrence, E. J., Shaw, P., Baker, D., Baron-Cohen, S., & David, A. S. (2004). Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the Empathy Quotient. Psychological Medicine, 34(5), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291703001624

Michaels, T. M., Horan, W. P., Ginger, E. J., Martinovich, Z., Pinkham, A. E., & Smith, M. J. (2014). Cognitive empathy contributes to poor social functioning in schizophrenia: Evidence from a new self-report measure of cognitive and affective empathy. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.054

Muncer, S. J., & Ling, J. (2006). Psychometric analysis of the empathy quotient (EQ) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1111–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.020

Pepper, K. L., Demetriou, E. A., Park, S. H., Boulton, K. A., Hickie, I. B., Thomas, E. E., & Guastella, A. J. (2019). Self-reported empathy in adults with autism, early psychosis, and social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research, 281, 112604–112604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112604

Schwenck, C., Mergenthaler, J., Keller, K., Zech, J., Salehi, S., Taurines, R., Romanos, M., Schecklmann, M., Schneider, W., Warnke, A., & Freitag, C. M. (2012). Empathy in children with autism and conduct disorder: group-specific profiles and developmental aspects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(6), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02499.x

Tone, E. B., & Tully, E. C. (2014). Empathy as a “risky strength”: A multilevel examination of empathy and risk for internalising disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4pt2), 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414001199

Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Dimaggio, G., & Fonagy, P. (2019). Mindfulness, Alexithymia, and Empathy Moderate Relations Between Trait Aggression and Antisocial Personality Disorder Traits. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1082–1090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1048-3

Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Goldenfeld, N., Delaney, J., Fine, D., Smith, R., & Weil, L. (2006). Development of short forms of the Empathy Quotient (EQ-Short) and the Systemising Quotient (SQ-Short). Personality and Individual Differences, 41(5), 929–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.017

Wheelwright, S., Baron-Cohen, S., Goldenfeld, N., Delaney, J., Fine, D., Smith, R., Weil, L., & Wakabayashi, A. (2006). Predicting autism spectrum quotient (AQ) from the systemizing quotient-revised (SQ-R) and empathy quotient (EQ): Multiple perspectives on the Psychological and neural bases of social cognition. Brain Research, 1079, 47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.012

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved