The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – 16 item version (DERS-16) is a self-report measure that assesses individuals’ levels of difficulties in emotion regulation. Based upon the original 36 item version DERS, the DERS-16 uses a clinically-useful conceptualisation of emotion regulation that was developed to be applicable to a wide variety of psychological difficulties.

Deficits in emotion regulation have been identified as a transdiagnostic factor underlying various psychological conditions (Murray et al., 2024). The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale 16 (DERS-16) is a 16-item self-report measure designed to briefly assess clinically-relevant difficulties in emotion regulation (Bjureberg et al., 2016).

Emotion regulation broadly refers to the intrinsic and extrinsic processes involved in monitoring, evaluating, and modulating emotional reactions in order to accomplish one’s goals (Thompson, 1994). Inherent within this definition of emotion regulation is the idea that emotions are functional, providing information about our environment and motivating behaviours that may facilitate adaptation to situational demands (Izard & Ackerman, 2000). Conversely, difficulties in the awareness, understanding, or modulation of emotion may interfere with adaptation and contribute to a wide range of negative outcomes. A growing body of research offers support for the role of emotion regulation difficulties in multiple forms of psychopathology and maladaptive behaviours (Cichetti, Ackerman, & Izard, 1995; Gratz & Tull, 2010; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Sheppes, Suri, & Gross, 2015).

The DERS-16 is derived from the longer DERS-36 (Gratz and Roemer, 2004) and omits the ‘Awareness’ subscale, evaluating five key aspects of emotion regulation:

The DERS-16 can be particularly useful in helping patients identify areas for growth in how they respond to their emotions, or for formulation and treatment planning transdiagnostically where emotion regulation difficulties feature, such as in borderline personality disorder, generalised anxiety disorder or substance use disorder.

The 16-item scale has been shown to perform on-par to the full 36-item DERS, capturing a similar amount of variance in psychiatric symptoms (Hallion et al., 2018). Given its brevity while maintaining clinical validity, clinicians should consider using the DERS-16 in settings where assessment time is limited. Indeed, researchers have suggested its use in community and clinical assessment to reduce respondent burden and for outcome monitoring (Sörman et al., 2022).

Research findings have demonstrated that difficulties in emotion regulation as measured by the DERS-16 are related to a range of other clinically relevant psychological constructs assessed by measures such as the AAQ, ASI-3, DASS, AUDIT, and FFMQ among others. To briefly summarise these associations, higher DERS-16 scores are correlated with higher levels of psychological inflexibility, negative emotional intensity, anxiety sensitivity, emotional impulsivity, borderline personality traits, general distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), alcohol use problems, disordered eating and self-harm behaviours. Further, those with higher DERS-16 scores tend to show lower levels of mindful awareness, descriptive emotional abilities, and capacity to reduce negative emotions (Bjureberg et al., 2016; Skutch et al., 2019; Sörman et al., 2022).

The total score ranges from 16-80 with higher scores indicating more difficulties with emotion regulation. Subscale raw scores have several ranges listed below:

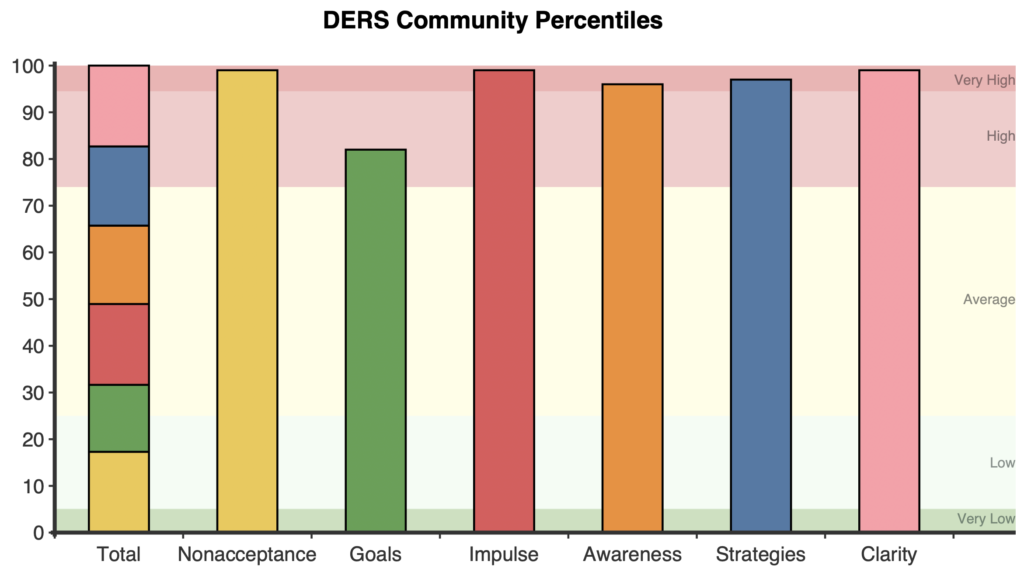

On first administration, a stacked bar graph shows the total and each of the six subscale scores in clinical percentiles. Percentiles give context to a client’s score, showing how they compare to their peers. For example, a percentile of 50 represents the typical level of difficulties with emotional regulation among treatment seeking adults.

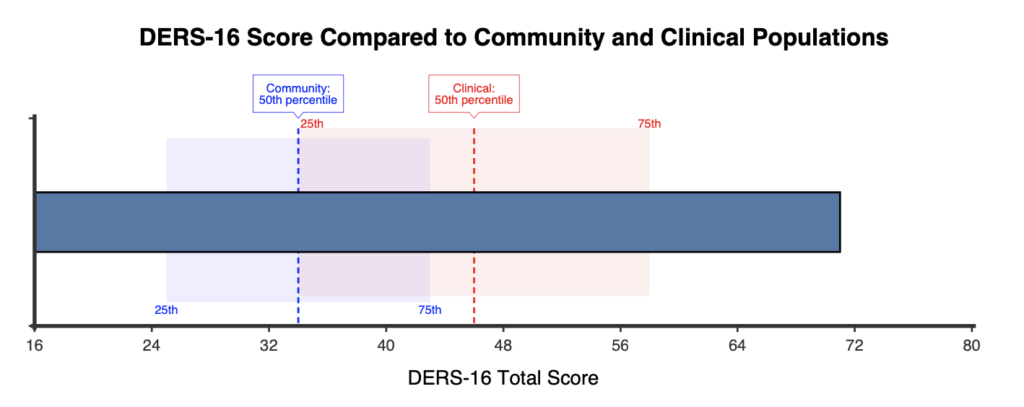

A horizontal comparison graph is also presented showing the respondent’s score in comparison to the normative community and clinical samples.

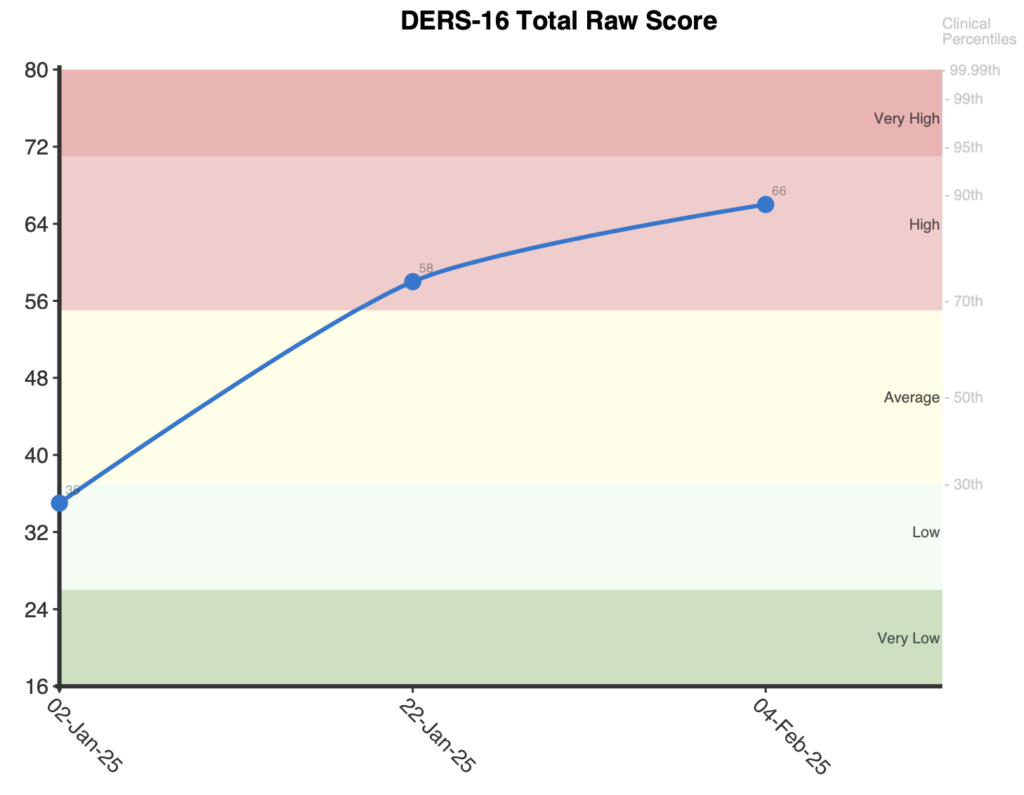

When administered more than once, a line graph is presented for the raw total score with clinical percentile labels on the right.

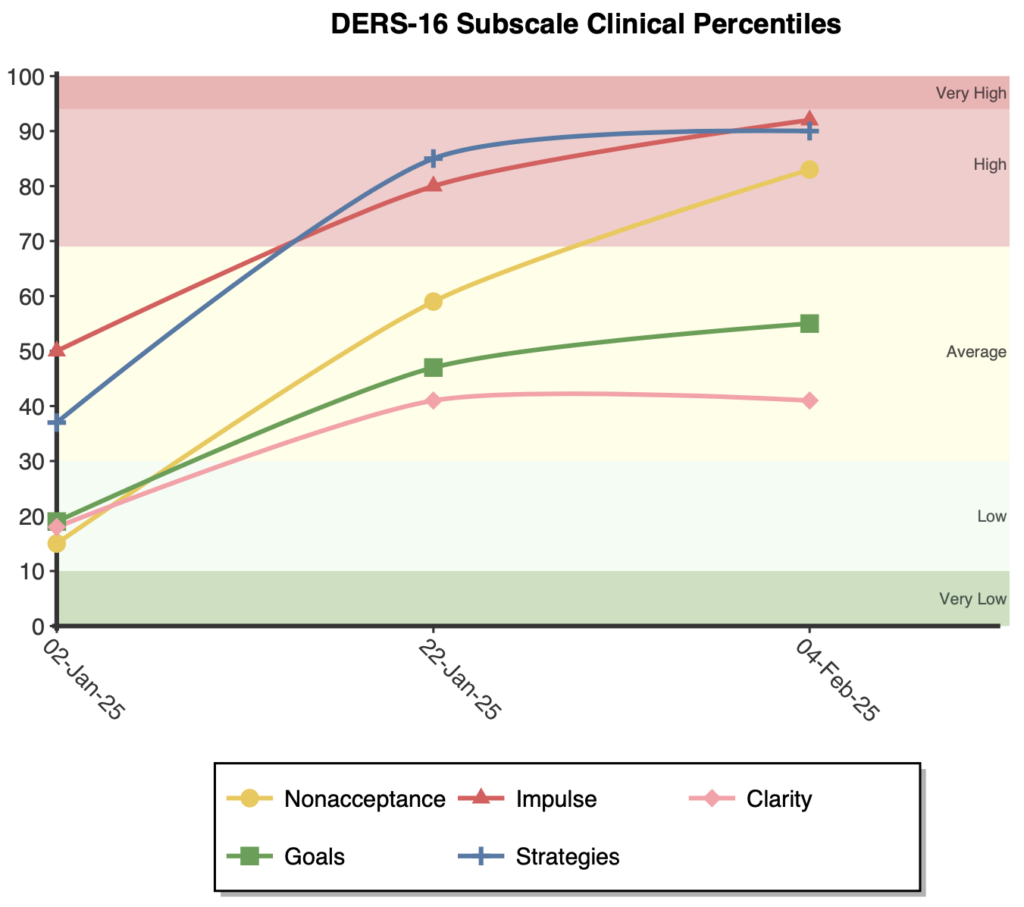

A second line graph is presented plotting each of the five subscales in clinical percentile terms.

Significant improvements or deterioration in the total score are indicated by shifts of half a standard deviation or greater (approximately 7.5 total score points or more) following the guidelines of the Minimally Important Difference (Turner et al., 2010).

Severity categories were created based on clinical percentiles from NovoPsych (2025) and in consideration of community percentiles derived from Bjureberg et al. (2016):

The DERS-16 demonstrates strong construct validity despite being significantly shorter than the DERS-36 and the removal of the emotional awareness subscale did not significantly diminish the scale’s relationship to awareness-related constructs–suggesting the 16-item version captures this aspect to similar effect (Bjureberg et al., 2016). Furthermore, the measure demonstrates temporal stability, with a 14-day test-retest reliability of ρI = .85 (Bjureberg et al., 2016).

The scale has strong internal consistency, with several investigations reporting high reliability for the total scale score: .90 (Lawlor et al., 2020), .92, .94 (Bjureberg et al., 2016) and .91 (Westerlund & Santtila, 2018). Indeed, the results of a NovoPsych (2025) analysis support these findings, with a PSI of .93 (person separation index; how reliably the scale distinguishes between individuals at different levels of emotional difficulty), in addition to a Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega of .94.

Several authors direct that the DERS-16 subscale scores should not be computed given the low number of items (Burton et al; Bjureberg et al). However, investigations of both community and clinical samples, found that subscale reliability ranged from acceptable to high .7-.9 (Lawlor et al., 2020; Westerlund & Santtila, 2018). In an analysis of NovoPsych (2025) data, excellent reliability values (alpha, omega) for each subscale were observed, ranging from .83-.88 (full details in table 2). Furthermore, seven CFA studies have replicated the 5-factor structure of the DERS-16, further supporting the use of subscales (Charak et al., 2019; Hallion et al., 2018; Lawlor et al 2020; Miguel et al., 2017; Shahabi et al., 2018; Westerlund & Santtila, 2018; Yiĝit & Yiĝit, 2017). It should also be noted that these CFA results do not invalidate the use of the total score—under a NovoPsych analysis, evidence of unidimensionality was observed via Smith’s (2005) test. Therefore, we encourage the calculation of the DERS-16 subscale and total scores as they are valid, reliable and useful.

The DERS-16 has also demonstrated strong measurement invariance across different populations. Charak et al. (2019) found measurement invariance between adolescent and adult samples, indicating the scale functions similarly across these age groups. A NovoPsych (2025) analysis (n=707) of differential item functioning supports these findings. NovoPsych (2025) looked at measurement invariance across ages ranging from 18-83 and found no evidence of differential item functioning (or “item bias”) by age. Bias testing was also conducted on gender and time taken to complete the assessment, with no bias being observed for these additional variables (NovoPsych, 2025).

Clinical norms have been reported from a sample of treatment-seeking adults (n=707) by NovoPsych (2025), with a mean total score of 45.88 (SD = 15.05). Table 1 provides further details, including subscale scores from this sample. Community norms are reported by Bjurberg et al. (2016) n=482 and Westerlund & Santtila (2018) n=409.

Severity categories were created based on the percentile ranges of the Clinical sample from NovoPsych (2025) and considering the community sample distribution from Bjurberg et al. (2016):

For subscales, data is reported for both clinical (Lawlor et al., 2020; NovoPsych, 2025) and community (Westerlund & Santtila, 2018) samples, and are detailed in table 1.

Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, L.-G., Bjärehed, J., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., Gumpert, C. H., & Gratz, K.L. (2016). Development and Validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 1–13. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x

Bartholomew, E., Smyth, C., Buchanan, B., Baker, S., Hegarty, D. (2025). A Review of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale 16 (DERS-16): Factor Structure, Reliability, Measurement Invariance, and Normative Data.

Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, L.-G., Bjärehed, J., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., Gumpert, C. H., & Gratz, K. L. (2016). Development and validation of a brief version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 284–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x

Burton, A. L., Brown, R., & Abbott, M. J. (2022). Overcoming difficulties in measuring emotional regulation: Assessing and comparing the psychometric properties of the DERS long and short forms. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), Article 2060629. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2060629

Charak, R., Byllesby, B. M., Fowler, J. C., Sharp, C., Elhai, J. D., & Frueh, B. C. (2019). Assessment of the revised Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scales among adolescents and adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 279, 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.010

Cicchetti, D., Ackerman, B. P., & Izard, C. E. (1995). Emotions and emotion regulation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006301

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Gratz, K. L., & Tull, M. T. (2010). Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 107–133). Context Press/New Harbinger Publications.

Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614536164

Hallion, L. S., Steinman, S. A., Tolin, D. F., & Diefenbach, G. J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and its short forms in adults with emotional disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00539

Izard, C. E., & Ackerman, B. P. (2000). Motivational, organizational, and regulatory functions of discrete emotions. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (2nd ed., pp. 253-264). Guilford Press.

Lawlor, C., Vitoratou, S., Hepworth, C., & Jolley, S. (2021). Self‐reported emotion regulation difficulties in psychosis: Psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS‐16). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(10), 2323–2340. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23164

Miguel, F. K., Giromini, L., Colombarolli, M. S., Zuanazzi, A. C., & Zennaro, A. (2017). A Brazilian investigation of the 36- and 16-item Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scales. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(9), 1146–1159. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22404

Shahabi, M., Hasani, J., & Bjureberg, J. (2018). Psychometric properties of the brief Persian version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (the DERS-16). Assessment for Effective Intervention, 45(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508418800210

Sheppes, G., Suri, G., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112739

Skutch, J. M., Wang, S. B., Buqo, T., Haynos, A. F., & Papa, A. (2019). Which brief is best? Clarifying the use of three brief versions of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41(3), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-019-09736-z

Smith, E. V. (2005). Effect of item redundancy on Rasch item and person estimates. Journal of Applied Measurement, 6(2), 147–163.

Sörman, K., Garke, M. Å., Isacsson, N. H., Jangard, S., Bjureberg, J., Hellner, C., Sinha, R., & Jayaram‐Lindström, N. (2022). Measures of emotion regulation: Convergence and psychometric properties of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23206

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2-3), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x

Westerlund, M., & Santtila, P. (2018). A Finnish adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ) and the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (DERS-16). Nordic Psychology, 70(4), 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2018.1443279

Yiğit, İ., & Yiğit, M. G. (2017). Psychometric properties of Turkish version of difficulties in emotion regulation scale-brief form (DERS-16). Current Psychology, 38(6), 1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9712-7

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved