The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 12-item self-report screening questionnaire designed to measure harmful alcohol use (Saunders et al., 1993a). This includes the 10 standard questions of the AUDIT and 2 questions at the end to determine self-identified problem drinking and self-perceived difficulty in stopping drinking.

The AUDIT is sensitive to three factors of problematic alcohol use:

The AUDIT differs from other self-report screening tests in that it was based on data collected from a large multinational sample, used a statistical rationale for item selection, emphasises identification of hazardous drinking rather than long-term dependence and adverse drinking consequences, and focuses primarily on symptoms occurring during the recent past rather than “ever”.

The AUDIT is widely used and useful for routine screening in community health settings and was developed in conjunction with the World Health Organisation (WHO). The AUDIT has been used in both clinical and non-clinical contexts. It has been effectively employed among adolescents aged 15 and older, adults, and older adults (Santis et al., 2009; Saunders et al., 1993a). Furthermore, it is regarded as a highly appropriate screening instrument for identifying unhealthy alcohol use across primary care and various healthcare environments (Saunders et al., 1993a).

Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood of hazardous and harmful drinking. Scoring is computed by adding scores (0 – 4) on questions 1 to 8, and questions 9 and 10 scored 0, 2, or 4 points. Questions 11 and 12 are not scored.

Risk levels are categorised using qualitative descriptors based on the following total scores:

Scores are also presented as a percentile compared to a sample of individuals from the community without an alcohol addiction (Moussas et al., 2009). A percentile of 50 indicates a typical score for someone from the general public, with higher percentiles indicating high severity. Percentiles of 81 and below (raw score of 7) indicate no drinking problem.

Total scores of 8 or more are recommended as indicators of hazardous and harmful alcohol use. However, a score of 8 or more will only be sensitive to 59% of individuals who actually have drinking problems (Bush et al, 1998). For women, a cut score of 8 on the AUDIT accurately identifies 73% who are at-risk drinkers (positive predictive value, or PPV = 0.73) and correctly rules out 77% of those who are not at risk (negative predictive value, or NPV = 0.77). For men, the assessment shows higher effectiveness, accurately identifying 91% of at-risk drinkers (PPV = 0.91) and correctly ruling out 86% of those who are not at risk (NPV = 0.86) (Demartini & Casey, 2012).

When looking at individual responses the questions can be conceptualised using the following three categories:

A raw score above 4 (average score 1.3) on the Dependence subscale indicates that the client may have alcohol dependency.

The last two questions help with managing self-beliefs about drinking problems and self-perceived difficulties in stopping or reducing drinking levels within the next 3 months.

The horizontal graph presents the total score in comparison to community, binge-drinking, and alcohol dependence distributions, with shaded areas around the two middle quartiles (between the 25th and 75th percentile). The binge-drinking distribution represents scores from individuals who have engaged in binge drinking in the last month. The alcohol dependence distribution represents individuals diagnosed with alcohol dependence and who are presenting for inpatient admission (Moussas et al., 2009). This graph helps contextualise patterns of responding in comparison to the distribution of responses among community and binge drinking samples and those with a diagnosis of alcohol addiction (Moussas et al., 2009).

Alcohol intake is intricately linked to various mental health conditions and life outcomes, often creating a cycle of adverse effects. High levels of alcohol consumption can exacerbate symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders, leading to a decline in overall mental well-being (Boschloo et al., 2012). Conversely, individuals struggling with mental health issues may turn to alcohol as a coping mechanism, resulting in increased consumption and dependency (Almeida-Filho et al., 2007). This cycle can significantly impact life outcomes, including deteriorating relationships and decreased work performance (Thorisson et al., 2019).

The AUDIT was developed in association with the WHO to create a simple, effective tool for identifying individuals with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption. The test was designed through a comprehensive review of existing research on alcohol use and its effects, incorporating feedback from clinical experts and users (Saunders et al., 1993b; Saunders et al., 1993b).

In a sample of 7905 university students (Mean age = 21.49, SD = 3.68, 46% males), the confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the scale consists of three factors:

The overall reliability of the scale was found to be high (Crohnbach’s alpha = .82) (Lopez et al., 2019). For the subscales, the reliability coefficients were:

The correlations between AUDIT scores and related constructs were statistically significant, providing evidence of sound construct validity. Specifically, the AUDIT had a significant positive correlation with stress, as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (r = .156, p < .001), loneliness (r = .114, p < .001) as measured by the Loneliness Scale Revised-Short. Furthermore, it was significantly correlated with psychological inflexibility (r = .176, p < .001), as measured by the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, and with symptoms of depression and anxiety (r = .169, p < .001), measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire of Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4) (Lopez et al., 2019).

The test development sample (Saunders et al, 1993a) consisted of 1888 individuals. Participants from primary health care facilities were categorised into ‘non-drinkers’ (36%), ‘drinking patients’ (48%), and ‘alcoholics’ (16%) based on their interview responses. Mean ages were 36.1 ± 10.9 for non-drinkers, 35.3 ± 10.2 for drinking patients, and 38.7 ± 9.2 for alcoholics. A cut-off value of 8 yielded sensitivities for various indices of problematic drinking that were in the mid-0.90s. Subsequent research has evaluated the AUDIT against other measures of alcohol problems including data from comprehensive interviews. One such study (Bush et al., 1998) found that among 477 participants who completed the AUDIT and were interviewed to determine significant alcohol-related problems, a cutoff score of 8 had a sensitivity (false negative) of 59% and a specificity (false positive) of 91%. That is, a score of 8 or more will only be sensitive to 59% of individuals who actually have drinking problems, and one can be 91% sure it is not a false positive.

For women, a cut score of 8 on the AUDIT accurately identifies 73% who are at-risk drinkers (positive predictive value, or PPV = 0.73) and correctly rules out 77% of those who are not at risk (negative predictive value, or NPV = 0.77). For men, the assessment shows higher effectiveness, accurately identifying 91% of at-risk drinkers (PPV = 0.91) and correctly ruling out 86% of those who are not at risk (NPV = 0.86) (Demartini & Casey, 2012).

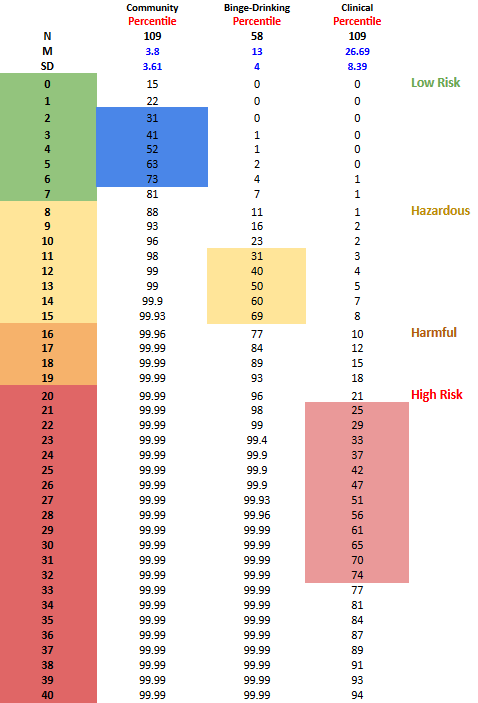

Data from Moussas et al. (2009) were used for community samples without alcohol addiction (Mean age = 39.66, SD = 12.80, 68.8% male), where the mean AUDIT score was 3.8 and the SD was 3.61. Another sample consistent of individuals diagnosed with alcohol addiction presenting for an inpatient admission (Mean age = 41.75, SD = 9.61, 48.6% male), the mean score was 26.69 with an SD of 8.39 (Moussas et al., 2009). Additionally, a sample of binge drinkers (Mean age = 22, SD = 2.6, 29% male) from Piano et al. (2015) reported a mean of 13 and an SD of 4. This data is used by NovoPsych to compute percentiles and present respondents’ scores effectively.

The percentile table below illustrates how total scores (see Table 1) compare to community, binge-drinking, and clinical populations (Moussas et al., 2009; Piano et al., 2015). Each score is accompanied by a corresponding percentile, indicating the percentage of individuals who scored the same or lower. For instance, a total score of 11 corresponds to the 98th percentile compared with the community sample, 31st percentile in the binge-drinking sample, and the 3rd percentile in a clinical sample (Table 1). This score signifies that 98% of the individuals in the community had a score of 11 or lower, whereas only 3% of people admitted to hospital for alcohol dependence . These graphs provide an understanding of a respondent’s standing relative to other individuals in the community, compared to a binge-drinking sample, and compared to individuals with alcohol addiction.

Table 1. AUDIT Total Score Community, Binge-Drinking, and Clinical Percentiles.

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Amundsen, A., & Grant, M. (1993a). Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-I. Addiction, 88(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00822.x

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993b). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Almeida-Filho, N., Lessa, I., Magalhães, L., Araúho, M. J., Aquino, E., & de Jesus, M. J. (2007). Co-occurrence patterns of anxiety, depression and alcohol use disorders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257(7), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-007-0752-0

Boschloo, L., Vogelzangs, N., van den Brink, W., Smit, J. H., Veltman, D. J., Beekman, A. T. F., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2012). Alcohol use disorders and the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.09755

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., Bradley, K. A., & Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of internal medicine, 158(16), 1789-1795. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789

Demartini, K. S., & Carey, K. B. (2012). Optimizing the use of the AUDIT for alcohol screening in college students. Psychological assessment, 24(4), 954–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028519

López, V., Paladines, B., Vaca, S., Cacho, R., Fernández-Montalvo, J., & Ruisoto, P. (2019). Psychometric properties and factor structure of an Ecuadorian version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in college students. PloS One, 14(7), e0219618-. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219618

Moussas, G., Dadouti, G., Douzenis, A., Poulis, E., Tzelembis, A., Bratis, D., Christodoulou, C., & Lykouras, L. (2009). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): reliability and validity of the Greek version. Annals of General Psychiatry, 8(11), 11–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859x-8-11

Piano, M. R., Tiwari, S., Nevoral, L., & Phillips, S. A. (2015). Phosphatidylethanol Levels Are Elevated and Correlate Strongly with AUDIT Scores in Young Adult Binge Drinkers. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(5), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv049

Santis, R., Garmendia, M. L., Acuña, G., Alvarado, M. E., & Arteaga, O. (2009). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening instrument for adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(3), 155–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.017

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Amundsen, A., & Grant, M. (1993a). Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-I. Addiction, 88(3), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00822.x

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993b). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Thørrisen, M. M., Bonsaksen, T., Hashemi, N., Kjeken, I., van Mechelen, W., & Aas, R. W. (2019). Association between alcohol consumption and impaired work performance (presenteeism): a systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(7), e029184–e029184. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029184

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved