The Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ) is a brief, 10-item, self-report measure of substance dependence intended to capture the essential elements of the dependence syndrome across all substance classes. The LDQ can provide clinicians and researchers with a unitary, continuous, measure of dependence that is not specific to any particular substance (Edwards & Gross, 1976; Edwards, 1986).

The LDQ provides a range of scores from 0-30 intended to capture the “graded intensity” of the dependence syndrome (Edwards, 1986). Its brevity, ease of administration and scoring, high content validity, and demonstrated patient acceptability means that the LDQ has excellent potential as a clinical and program evaluation tool. The LDQ has demonstrated utility as a measure sensitive to change in response to substance use disorder treatment among adults treated for alcohol, heroin, methadone, stimulant, and opiate dependence (Raistrick et al., 2014; Tober et al., 2000).

The 10 items map onto the ICD-10 and DSM criteria for substance dependence: Pre-occupation, salience, compulsion to start, planning, maximising effect, narrowing of repertoire, compulsion to continue, primacy of effect, constancy of state, and cognitive set.

Example LDQ Items:

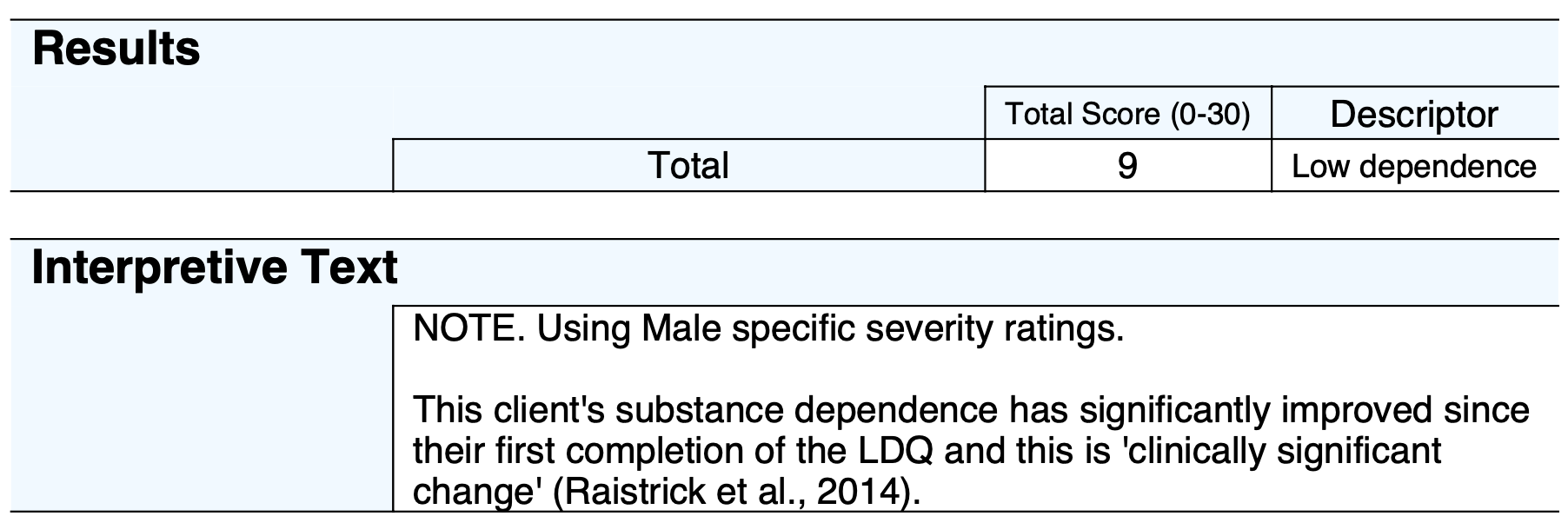

A total score is presented (0 – 30) where a higher score is indicative of more severe substance dependence. It is best to see substance dependence as continuum; the higher the score, the stronger the dependence. As scores get higher it is more difficult to cut down on substance use.

For ease of reference, descriptors are provided for the total score based upon prior research. Scores of 10 or less are considered to be “low dependence” for males and scores of 5 or less for females (Raistrick et al., 2014; note that 8 or less is chosen if no gender was specified but this should be interpreted with caution) whereas scores between 11 (or 6 or 9, depending upon gender) and 20 are considered to be “moderate dependence” and scores above 20 are considered “high dependence” (Patton-Simpson & MacKinnon, 1999).

Given that a reliable change score of 4 was determined by Raistrick et al. (2014), interpretive text will be provided upon multiple administrations of the LDQ to outline changes from the initial score for the client. The clinically significant change score was 10 or less for males and 5 or less for females (Raistrick et al., 2014).

Psychometric data indicate the instrument is a robust, unidimensional, measure of substance dependence severity (Heather et al., 2001; Raistrick et al., 1994). A principal components analysis produced a single factor solution that accounts for 58 – 64% of the variance (Kelly et al., 2013; Heather et al., 2001; Raistrick et al. 1994). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of reliability ranged from 0.90 – 0.94 (Kelly et al., 2013; Heather et al., 2001; Raistrick et al. 1994). Corrected item total correlations, a measure of the correlation between each question score and the sum of the remaining scores was lowest for questions 5 and 8, but still reaching 0.66 and 0.69, respectively. Test-retest reliability was estimated on a sample of subjects (n = 33) with a mixed range of dependence levels and was carried out over an interval of 2-5 days. Total score retest reliability was 0.95 (Raistrick et al. 1994).

Raistrick et al. (2014) found significant differences between males and females for scores on the LDQ in a clincial population (n = 653; 52.4% male; males = 17.8, females = 10.9). Raistrick et al. (2014) determined the reliable change score for the LDQ was 4 and the cut-off for clinically significant change was a score of 10 for males and 5 for females.

Raistrick, D., Bradshaw, J., Tober, G., Weiner, J., Allison, J., & Healey, C. (1994). Development of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ): a questionnaire to measure alcohol and opiate dependence in the context of a treatment evaluation package. Addiction , 89(5), 563–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03332.x

Edwards G. (1986). The alcohol dependence syndrome: a concept as stimulus to enquiry. British journal of addiction, 81(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00313.x

Edwards, G., & Gross, M. M. (1976). Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. British medical journal, 1(6017), 1058–1061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058

Heather, N., Raistrick, D., Tober, G., Godfrey, C., & Parrott, S. (2001). Leeds Dependence Questionnaire: New Data from a Large Sample of Clinic Attenders. Addiction Research & Theory, 9(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350109141753

Kelly, J. F., Magill, M., Slaymaker, V., & Kahler, C. (2010). Psychometric validation of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ) in a young adult clinical sample. Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.005

Paton-Simpson, G., & MacKinnon, S. (1999). Evaluation of the Leeds Dependence Questionnaire (LDQ) for New Zealand. Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand. https://www.hpa.org.nz/sites/default/files/imported/field_research_publication_file/Leeds.pdf

Raistrick, D., Tober, G., Sweetman, J., Unsworth, S., Crosby, H., & Evans, T. (2014). Measuring clinically significant outcomes – LDQ, CORE-10 and SSQ as dimension measures of addiction. Psychiatric Bulletin (2014), 38(3), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.112.041301

Tober, G., Brearley, R., Kenyon, R., Raistrick, D., & Morley, S. (2000). Measuring Outcomes in a Health Service Addiction Clinic. Addiction Research & Theory, 8(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350009004418

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved