The CORE Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) is a self-report measure of psychological distress designed to be administered during a course of treatment to determine treatment response. The broad spectrum nature of the measure means it captures a wide variety of problems associated with mental health difficulties, beyond typical symptom measures. The copyright holder for the CORE-OM is the CORE System Trust.

The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) is a 34-item self-report scale developed to assess psychological distress and functioning across a variety of settings in the last week (Evans et al., 2002). It serves as a general measure of mental health, capturing a broad range of psychological and functional domains.

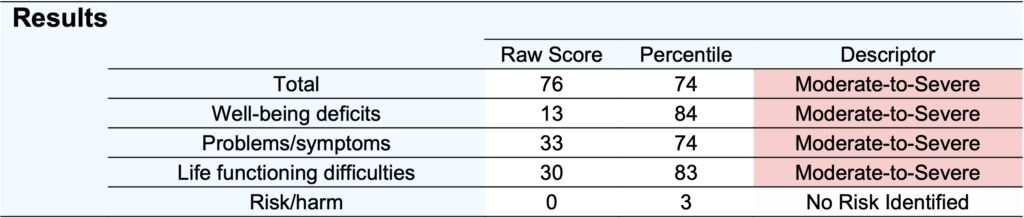

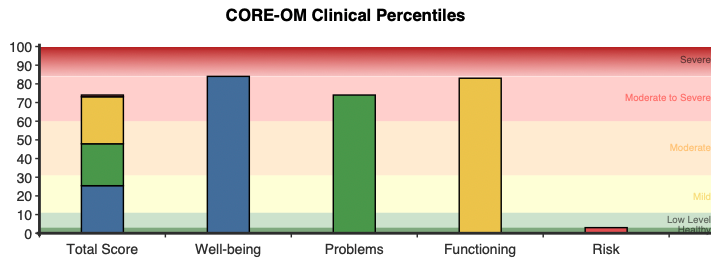

Four domains assessed by the CORE-OM:

· Well-being Deficits – overall sense of self-worth and positivity about life.

· Problems/Symptoms – psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, trauma, and physical symptoms.

· Life Functioning difficulties – social, general, and close relationship functioning.

· Risk/Harm – risk factors related to harm to self and others, as well as impulsivity.

A shorter derivative of the CORE-OM, the CORE-10, is designed for session-to-session routine outcome monitoring, while the CORE-OM is a more comprehensive measure. The CORE-OM is used widely in clinical practice for tracking client progress and assessing treatment outcomes. Its emphasis on both positive and negative aspects of mental health allow practitioners to gain a well-rounded understanding of a clients’ experiences, aiding in targeted intervention and treatment planning.

The scale has been validated in a diverse range of clinical and community settings, including primary and secondary care (Barkham et al., 2007; Barkham et al., 2005a). Research has shown it can effectively discriminate between clinical and non-clinical populations, and is suitable for use with older and younger (18+) adults (Barkham et al., 2005b; Beck et al., 2015).

CORE-OM items assess a range of issues, such as feelings of self-worth, anxiety, interpersonal difficulties, and thoughts related to harm. Specific sub-types of harm are assessed, including self-harm and harm to others, identifying individuals at heightened risk to themselves and/or others.

Research has shown the CORE-OM to correlate with both therapy attendance and treatment duration, suggesting that initial scores can indicate the length and engagement of treatment (Barkham et al., 2007; Biringer & Bjørkvik, 2024). Strong correlations to other established outcome measures, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Outcome Questionnaire-45 (OQ-45) have also been observed (Barkham et al., 2007; Barkham et al., 2005a).

Both a raw score and a clinical percentile are given for the total scale and each of the four subscales. Higher scores indicate poorer well-being, greater distress, more functional impairment, and higher risk across the past week.

Scores are presented as a percentile compared to a clinical sample, where a percentile of 50 represents the average psychological distress of someone seeking intervention.

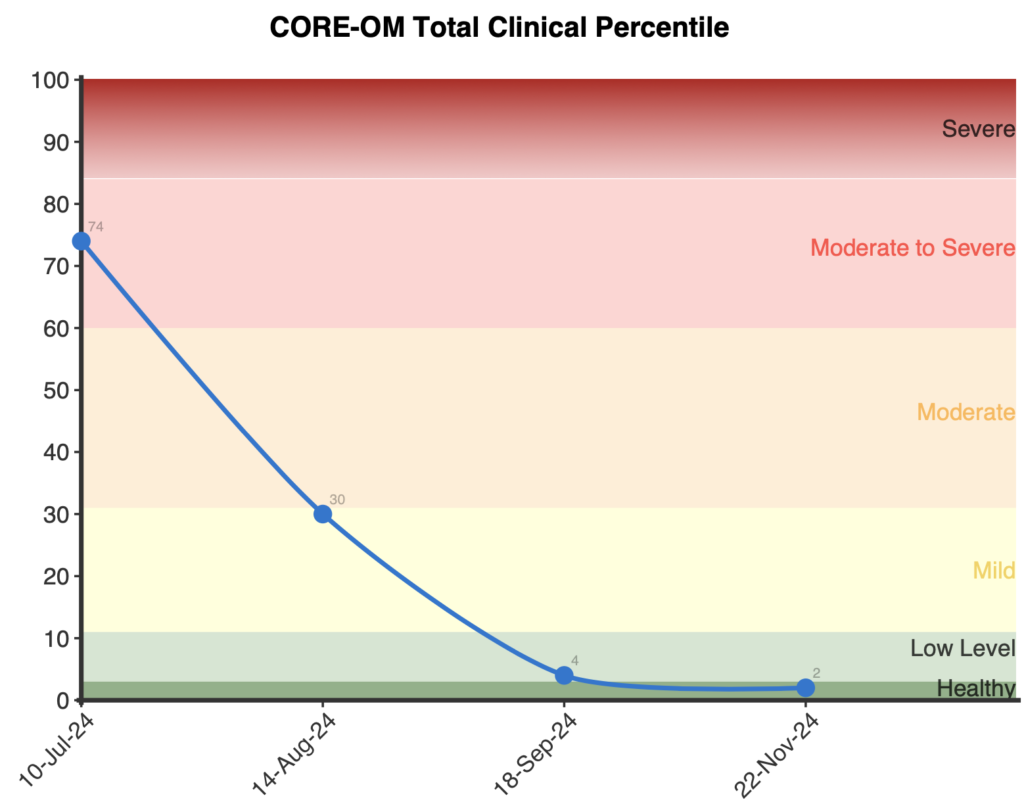

When administered more than once, two graphs are produced. The first shows the total percentile over time, which compares respondents’ total score to others seeking mental health support. The second graph represents subscale percentiles over time and is helpful for understanding the areas of improvement or deterioration and therefore targets for treatment. Both graphs can be useful in providing feedback to clients and assessing treatment response.

Severity ranges are reported for the CORE-OM, ranging from Healthy to Severe:

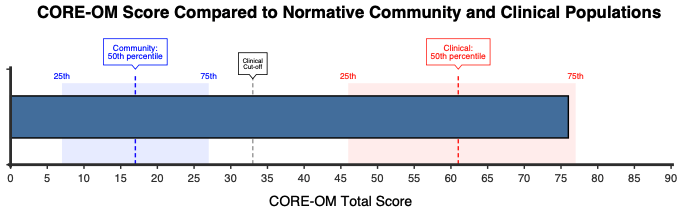

A total raw score of 33 is the established cut-off for distinguishing between clinical and non-clinical populations (Barkham et al., 2006; Connell et al., 2007).

A change of 17 raw score points or more is considered to exceed the reliable change index (RCI) threshold for changes that may be due to measurement error or chance acting alone, indicating meaningful improvement or deterioration (Barkham et al., 2006).

Therefore, to be sure that a client has made a reliable change, a score difference of 17 or more should be observed. Given that most of the severity ranges are approximately 17 points in size, a person scoring at the higher end of moderate (65) will move to the ‘mild’ range if their score exceeds the RCI. Typically, a score that exceeds the RCI corresponds with a change in severity level, with the exception being the severe category (Barkham et al., 2006).

The CORE-OM has demonstrated strong psychometric properties across various studies and populations, supporting the scale’s reliability and validity. Barkham and colleagues (2001) reported significant differences (p < .0005) between clinical and nonclinical samples for the CORE-OM total and subscales. Alpha values for the total and subscales were observed in both a clinical sample (n=713): Subjective Well-Being (a=.75), Problems (a=.88), Functioning (a=.87), Risk (a=.79), and total (a=.94), and a non-clinical sample (n=1,009): Subjective Well-Being (a=.77), Problems (a=.90), Functioning (a=.86), Risk (a=.79), and total (a=.94). These findings are supported by later investigations, which saw alpha coefficients range from 0.75 to 0.94 across different domains and samples, supporting the measure’s internal consistency reliability across clinical and non-clinical populations (Handscomb et al., 2016; Skre et al., 2013). Test-retest reliability has also been reported at 0.91 for 1-month and .80 for 4 months, indicating good stability of the measure over time (Barkham et al., 2007).

Factor analysis of the CORE-OM has led to varying interpretations of its structure. Originally designed with four domains—well-being, symptoms, functioning, and risk. A three-factor structure has also been suggested, separating risk from other items (Connell et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2018). Additionally, a two-factor solution, with general psychological distress and a risk component has demonstrated good fit. However, this has been tested only in clinical samples (Handscomb et al., 2016; Mavranezouli et al 2013).

Convergent validity of the CORE-OM has been well-established through correlations with measures of mental health, including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), with correlations ranging from 0.65 to 0.85 (Connell et al., 2007; Handscomb et al., 2016). Measurement invariance analyses have shown that the CORE-OM maintains comparability across time, even in populations undergoing significant therapeutic change, supporting its use in both research and routine outcome monitoring (Murray et al., 2018).

Clinical percentiles have been updated by combining responses from the CORE manual by Evans and colleagues (2000) n=863, Connell et al. (2007) n=10,761, and NovoPsych (n=2,346) into a weighted mean and pooled standard deviation.

Normative percentiles from non-distressed respondents and the general population are also reported, below are the clinical and general sample percentiles mapped to raw scores by severity range.

General:

Clinical:

Subscale percentiles are also available from 2,140 patients receiving therapy in the UK (Lyne et al., 2006).

The copyright holder for the CORE-OM is the CORE System Trust https://www.coresystemtrust.org.uk/home/instruments/core-om-information/

Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

Barkham, M., Gilbert, N., Connell, J., Marshall, C., & Twigg, E. (2005a). Suitability and utility of the CORE-OM and CORE-A for assessing severity of presenting problems in psychological therapy services based in primary and secondary care settings. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.3.239

Barkham, M., Culverwell, A., Spindler, K., & Twigg, E. (2005b). The CORE-OM in an older adult population: psychometric status, acceptability, and feasibility. Aging & mental health, 9(3), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500090052

Barkham, M., Mellor-Clark, J., Connell, J., & Cahill, J. (2006). A core approach to practice-based evidence: A brief history of the origins and applications of the CORE-OM and CORE System. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 6(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140600581218

Biringer, E., & Bjørkvik, J. (2024). Is there a prospective association between psychological distress as measured by the CORE-OM and treatment attendance and treatment duration? A follow-up study at a Norwegian Community Mental Health Centre. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 78(3), 220-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2024.2306217

Beck, A., Burdett, M., & Lewis, H. (2015). The association between waiting for psychological therapy and therapy outcomes as measured by the CORE-OM. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12072

Bedford, A., Lukic, G., & Tibbles, J. (2011). Evaluation of risk by patients’ and clinicians’ ratings: A CORE-OM and CORE-A investigation. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.714

Connell, J., Barkham, M., Stiles, W. B., Twigg, E., Singleton, N., Evans, O., & Miles, J. N. V. (2007). Distribution of CORE-OM scores in a general population, clinical cut-off points, and comparison with the CIS-R. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017657

Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

Handscomb, L., Hall, D. A., Hoare, D. J., & Shorter, G. W. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis of Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-OM) used as a measure of emotional distress in people with tinnitus. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0524-5

Lorentzen, V., Handegård, B. H., Moen, C. M., Solem, K., & Skre, I. (2020). CORE-OM as a routine outcome measure for adolescents with emotional disorders: Factor structure and psychometric properties. BMC Psychology, 8, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00459-5

Mavranezouli, I., Brazier, J. E., Rowen, D., & Barkham, M. (2013). Estimating a preference-based index from the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE-OM): Valuation of CORE-6D. Medical Decision Making, 33(4), 381-395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X12464431

Murray, A. L., McKenzie, K., Murray, K., & Richelieu, M. (2018). Examining response shifts in the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation- Outcome Measure (CORE-OM). British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1483007

Ona, J. V., Evans, C., & Paz, C. (2024). Clinical utility of the CORE-OM and CORE-10: An exploratory study in psychotherapy services in Ecuador. Collabra: Psychology, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.121932

Paz, C., Adana-Díaz, L., & Evans, C. (2020). Clients with different problems are different and questionnaires are not blood tests: A template analysis of psychiatric and psychotherapy clients’ experiences of the CORE-OM. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 276-285. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12290

Skre, I., Friborg, O., Elgarøy, S., Evans, C., Myklebust, L. H., Lillevoll, K., Sørgaard, K., & Hansen, V. (2013). The factor structure and psychometric properties of the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) in Norwegian clinical and non-clinical samples. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-99

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved