The Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire (ASA-27) is a self-report measure used to assess symptoms of adult separation anxiety such as excessive worry, distress, and avoidance linked to separation from loved ones or familiar places (Manicavasagar et al., 2003) .

The Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire was developed using the diagnostic criteria for separation anxiety disorder found in the DSM (Manicavasagar et al., 2003). The scale is primarily used as a screening tool to identify separation anxiety disorder in adults and assess the severity of symptoms, particularly among clinical populations or those with average to high levels of Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder (ASAD) in the community. It should be noted that ASAD is also referred to as SEPAD, Separation Anxiety Disorder in Adults.

Research reported in the International Journal of Epidemiology of over 665,000 individuals found that 6.7% experienced an anxiety disorder in the past 12 months (Steel et al., 2014). Among anxiety disorders, separation anxiety has gained recognition as a significant condition impacting adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Patel et al., 2021). Traditionally considered a childhood condition, the DSM-5 expanded the criteria to include the manifestation of separation anxiety disorder in adulthood. Symptoms involve excessive fear or distress associated with separation from attachment figures or familiar environments, persistent worry about harm to loved ones, often manifesting in avoidance behaviours, dependence, or heightened emotional responses and even physical symptoms such as nausea or headache in actual or anticipated separation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In therapy, the ASA-27 can be integrated into formulation, provide important detail for attachment-informed therapies and shape the clinician’s approach to developing the therapeutic relationship. The scale can assist with the identification of treatment targets and interventions, such as the development of adaptive strategies for self-regulation and meeting attachment needs, as well as promoting self-awareness. Early evidence suggests that the presence of ASAD may influence treatment outcomes for individuals with comorbid anxiety disorders, highlighting the importance of ASAD identification and targeted interventions (see Silove et al., 2010).

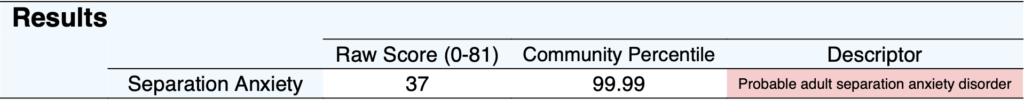

ASA-27 results are reported in raw scores ranging from 0-81. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms of adult separation anxiety.

Raw score descriptors are presented using primary (≥22) and high sensitivity cut offs (≥16):

Percentiles are also provided to allow comparison of the respondent’s score to a community sample, where a percentile of 50 represents the average psychological distress of a member of the general population.

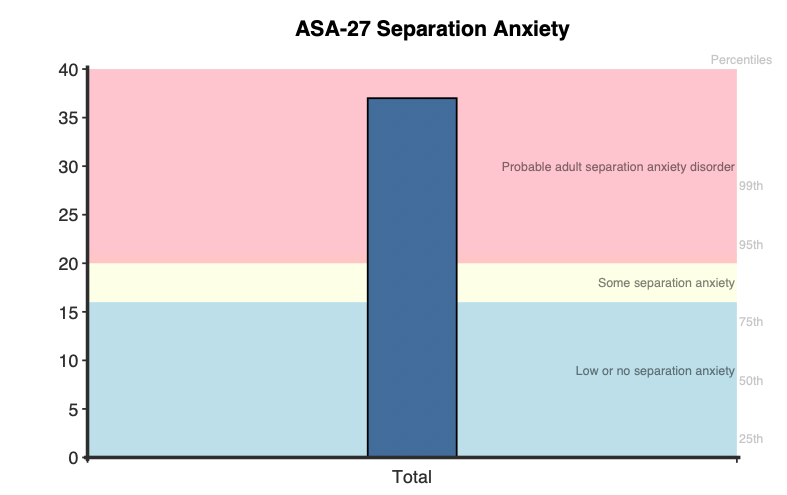

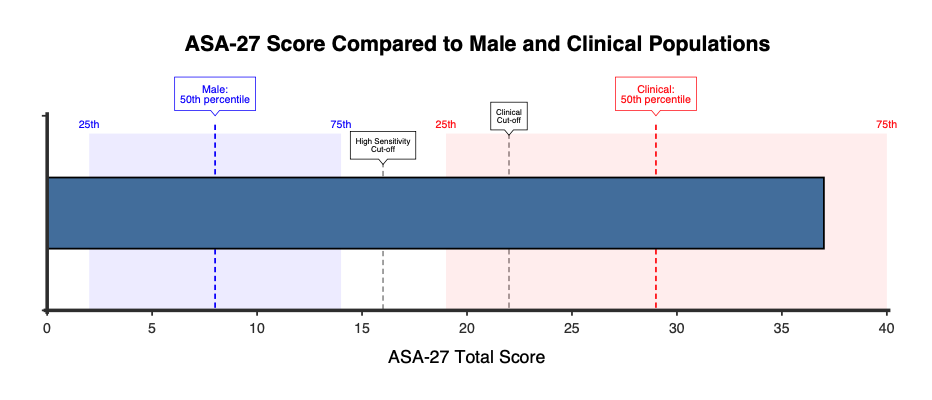

On first administration, a bar graph displaying the total raw score is presented, with three coloured ranges indicating Low or no separation anxiety (0-15), Some separation anxiety (16-21), and Probable adult separation anxiety disorder (≥22).

A horizontal bar graph is also shown, which compares the respondent’s score to the distributions of both clinical and general populations.

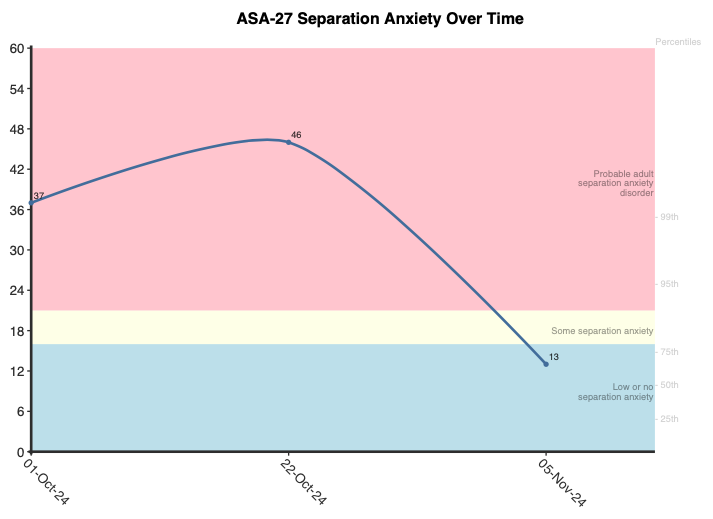

When administered more than once, a graph showing the total raw score over time is produced. This is useful for tracking symptom progression, monitoring treatment progress or providing clients with feedback.

Research has shown that ASA-27 scores have a relationship with important psychobiological constructs. For example, higher scale scores have been associated with reduced mitochondrial translocator protein (TSPO) expression and density—key indicators of proper stress and anxiety regulation. This suggests that greater adult separation anxiety can result in dysregulated biological responses to stress (Abelli et al., 2010). Furthermore, ASA-27 scores have been linked to behavioural inhibition (shyness, withdrawal, fearfulness), a temperamental predisposition originating in childhood that can persist into adulthood and is a risk factor for developing an anxiety disorder (Pini et al., 2022).

The ASA-27 could also be used to give insight into risk, as higher scores have been linked with elevated suicidal risk (measured via scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) in outpatients diagnosed with mood and anxiety disorders. Specifically, outpatients with a score above the cut off for ASAD had 1.86x higher odds of experiencing suicidal thoughts compared to those with a score lower than the cut off (Pini et al., 2021).

Psychometric studies of the ASA-27 support its validity and reliability in both clinical and community settings. Internal reliability has been observed to be strong, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.89 to 0.95 across studies (Finsaas et al., 2020; Manicavasagar et al., 2003). Additionally, test-retest reliability over an average three-week interval (r = 0.86, p < .001), indicating stability of the measure over time (Manicavasagar et al., 2003). Principal components analysis has consistently revealed a unidimensional structure, with a dominant first factor accounting for 45% of the variance and item loadings ranging from 0.38 to 0.80 (Finsaas et al., 2020).

Convergent validity is supported by significant correlations with structured interview assessments for ASAD (Manicavasagar et al., 2003). The scale also demonstrated significant relationships with measures of related constructs, including complicated grief, peritraumatic dissociation, and avoidance/intrusion symptoms (Carmassi et al., 2015; Gesi et al., 2017). Items reflect DSM-derived criteria for ASAD, and items based on these criteria exhibit stronger construct relevance compared to non-DSM items, as confirmed by item response theory analyses (Finsaas et al., 2020). Furthermore, item discrimination parameters show the scale is able to differentiate individuals at varying levels of moderate to severe symptoms, and the scale is invariant or unbiased by gender (Finsaas et al., 2020).

Two cut off scores are provided, a primary point of ≥22, and a lower, high sensitivity cut off of ≥16. The primary cut off possesses a high sensitivity (81%) and specificity (84%) and an area under the curve of .9, supporting its ability to distinguish individuals with clinically significant ASAD from those without it (Carmassi et al., 2015; Manicavasagar et al., 2003). The alternative, high sensitivity cut off (≥16) aims to provide a wide net approach, making sure (at a 97% sensitivity) to capture all ASAD cases while making concessions to include non-cases. This results in a situation where a clinician can be confident that their client is not being incorrectly overlooked, but requires a more thorough evaluation.

Clinical and general population percentiles are available, computed by NovoPsych based on mean and standard deviation scores (Bartholomew et al., 2024). The clinical sample consisted of 509 (34% male and 66% female) psychiatric outpatients with mood and anxiety disorders, with a mean age (SD) of 32.62(11.12) years, and a mean gender-combined score (SD) of 29.11(15.6) (Pini et al., 2021). The female non-clinical sample included 482 participants from the general population, with a mean age (SD) of 41.8(4.8). This group had a mean score (SD) of 10.34(9.61). The male non-clinical sample included 407 general population participants, with a mean age (SD) of 43.3(5.7). This group had a mean score (SD) of 8.10(8.46) (Finsaas et al., 2020).

Below are the clinical and general sample percentiles mapped to raw scores broken up by the standard (≥22) and high sensitivity (≥16) cut scores.

Community, Female:

Community, Male:

Clinical, Combined Gender:

Manicavasagar, V., Silove, D., Wagner, R., & Drobny, J. (2003). A self-report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(2), 146–153.

Abelli, M., Chelli, B., Pini, S., et al. (2010). Reductions in platelet translocator protein density are associated with adult separation anxiety. Neuropsychobiology, 62(2), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1159/000315440

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Bartholomew, E., Hegarty, D., Smyth, C., Baker, S., Buchanan, B. (2024). A Review of the Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire (ASA-27): Community and Clinical Norms, Category Descriptors and Psychometric Properties.

Carmassi, C., Gesi, C., Corsi, M., Pergentini, I., Cremone, I. M., Conversano, C., Perugi, G., Shear, M. K., & Dell’Osso, L. (2015). Adult separation anxiety differentiates patients with complicated grief and/or major depression and is related to lifetime mood spectrum symptoms. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.012

Finsaas, M. C., Olino, T. M., Hawes, M., Mackin, D. M., & Klein, D. N. (2020). Psychometric analysis of the adult separation anxiety symptom questionnaire: Item functioning and invariance across gender and time. Psychological Assessment, 32(6), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000815

Gesi, C., Carmassi, C., Shear, K. M., Schwartz, T., Ghesquiere, A., Khaler, J., & Dell’Osso, L. (2017). Adult separation anxiety disorder in complicated grief: An exploratory study on frequency and correlates. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 72, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.09.002

Manicavasagar, V., Silove, D., Wagner, R., & Drobny, J. (2003). A self-report questionnaire for measuring separation anxiety in adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1053/comp.2003.50024

Patel, A. K., & Bryant, B. (2021). Separation anxiety disorder. JAMA, 326(18), 1880–1880. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.17269

Pini, S., Abelli, M., Costa, B., Schiele, M. A., Domschke, K., Baldwin, D. S., Massimetti, G., & Milrod, B. (2022). Relationship of behavioral inhibition to separation anxiety in a sample (N = 377) of adult individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 116, 152326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152326

Pini, S., Abelli, M., Costa, B., Martini, C., Schiele, M. A., Baldwin, D. S., Bandelow, B., & Domschke, K. (2021). Separation Anxiety and Measures of Suicide Risk Among Patients With Mood and Anxiety Disorders. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(2), 20m13299. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13299

Steel, Z., Marnane, C., Iranpour, C., Chey, T., Jackson, J. W., Patel, V., & Silove, D. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038

Silove, D.M., Marnane, C.L., Wagner, R. et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult separation anxiety disorder in an anxiety clinic. BMC Psychiatry 10, 21 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-21

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved