The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) is a 16-item scale designed to measure burnout across adults employed in various occupational settings. The OLBI measures both physical and cognitive aspects of burnout as well as disengagement from work.

The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) is a psychometric scale designed to measure burnout across adults employed in various occupational settings (Demerouti, 1999). The OLBI aims to provide a measure of burnout that includes both physical and cognitive aspects of exhaustion, as well as the concept of disengagement from work.

This is reflected in two subscales:

Burnout is included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon as opposed to a mental disorder. Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterised by three dimensions:

Reduced professional efficacy. According to the ICD-11, burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life

Example OLBI items:

The OLBI is a versatile tool, suitable for use in a variety of clinical or other occupational population settings. Its primary uses include screening employees for burnout, identifying burnout and monitoring outcomes by tracking burnout over time.

The scale has been used in such disparate populations as healthcare workers, aircraft technicians, radiology residents, IT professionals, lawyers, firefighters and electrical engineers among others (Shoman et al., 2021; Raju et al., 2022; Innstrand et al., 2016). It is therefore application across work settings and professions.

Burnout among professionals has been shown to have a deleterious effect on work outcomes. In particular, burnout among mental health professionals impacts therapy outcomes negatively, making the OLBI a helpful self monitoring tool for clinicians providing mental health treatment (Delgadillo et al., 2018).

The OLBI is useful not only in screening for burnout and monitoring changes over time, but also for evaluating treatments/interventions to reduce burnout. A major strength is its focus on both exhaustion and disengagement, providing a quick evaluation of burnout and occupational well-being.

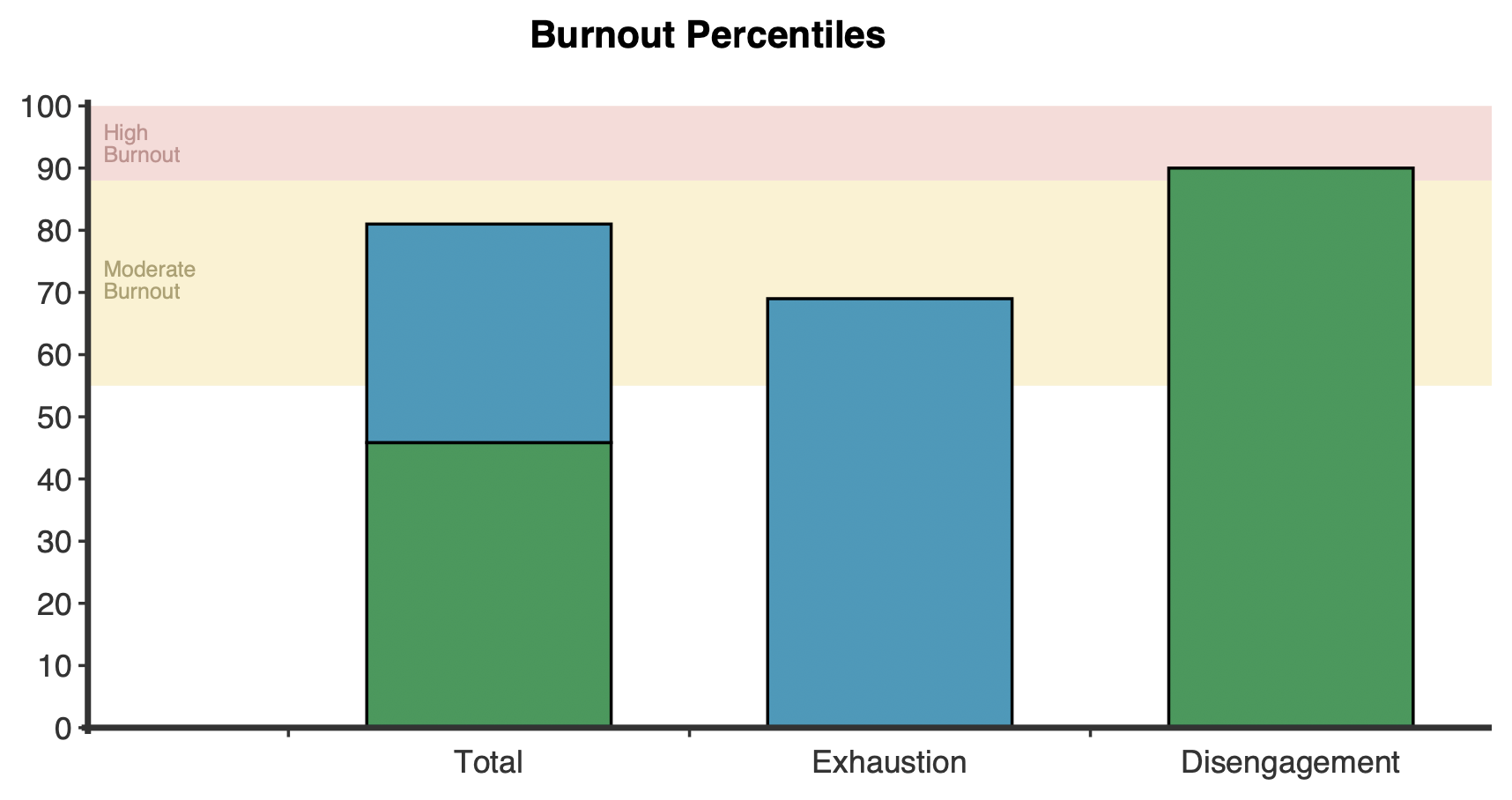

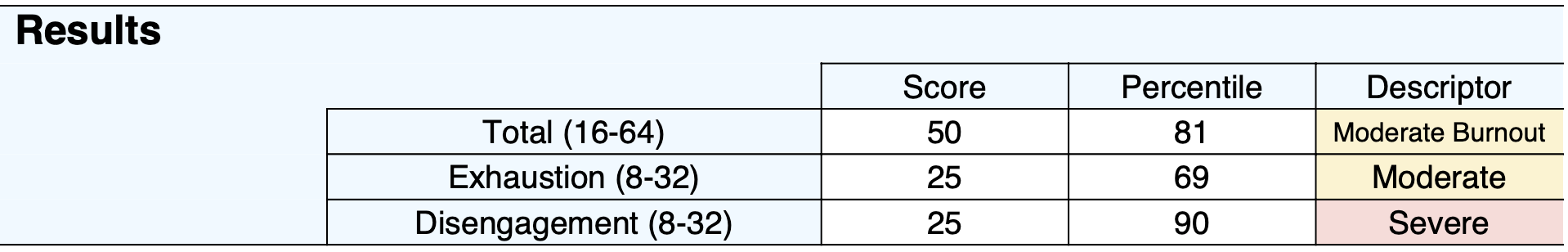

Subscale scores are included, with each subscale having a possible range of 8 to 32:

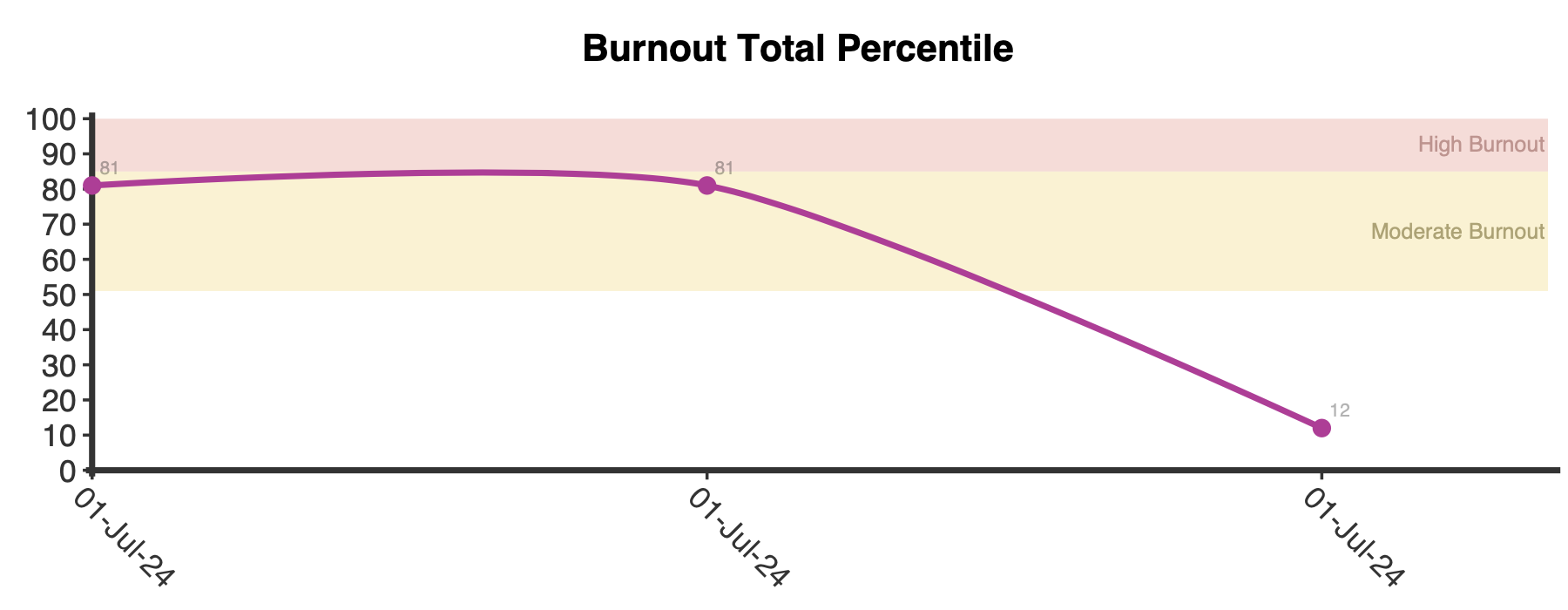

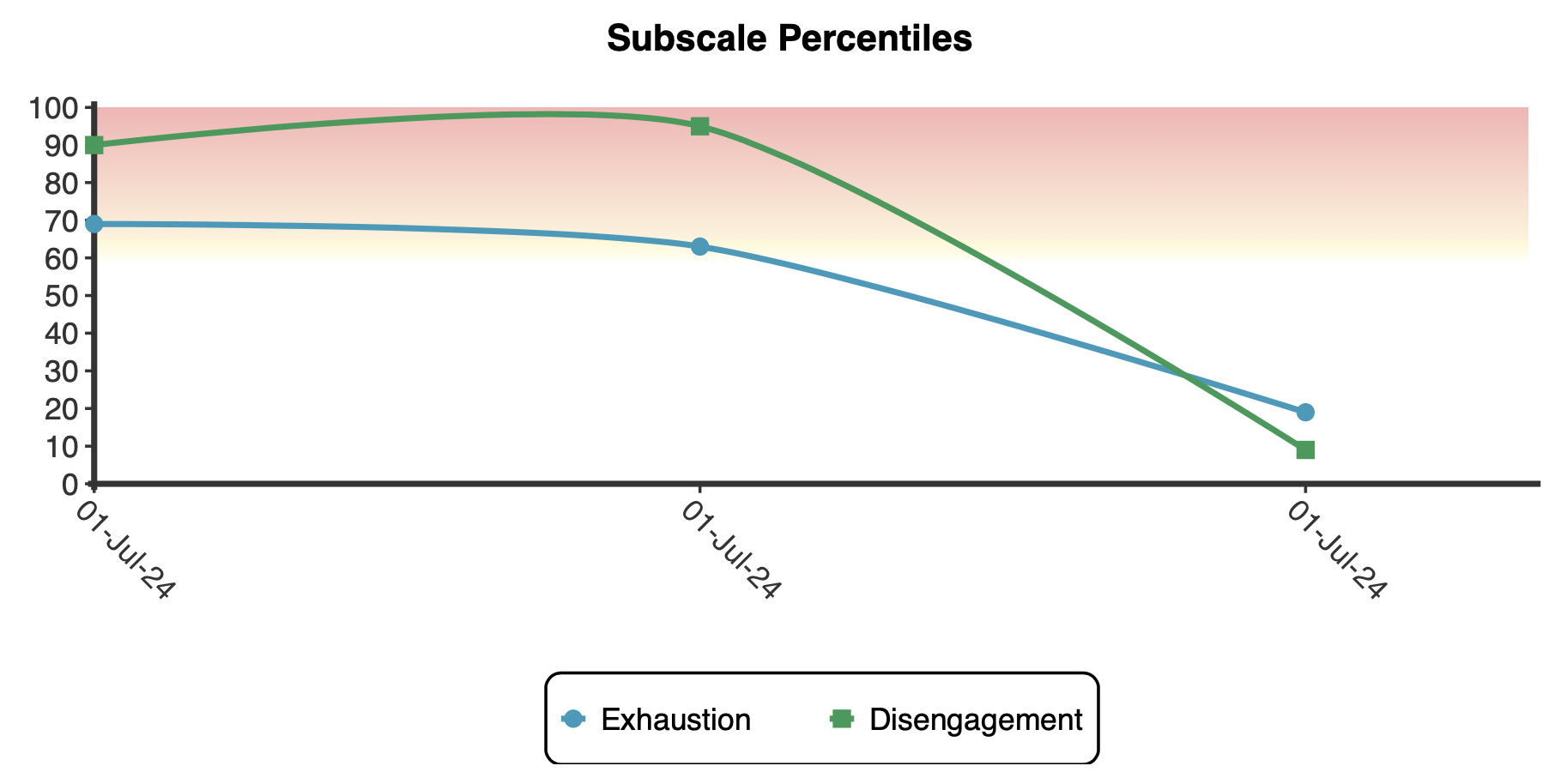

If administered more than once a line graph will be produced for the total and subscale percentiles. Changes are evaluated against a miniminally important difference threshold of half a standard deviation or mor (Norman et al., 2003).

First created in Germany by Demerouti, (1999) the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory was later validated in English (Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005). The scale was developed to overcome limitations found in other burnout measures such as the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and Professional Quality of Life scale (ProQOL), particularly in its applicability beyond human service professions and one-sided question framing (Demerouti et al., 2003).

The OLBI has undergone extensive validation across different cultural and occupational groups. Reliability indices are typically reported on a subscale basis, and support the internal consistency of the scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients range from .74 to .87 for the exhaustion subscale and from .70 to .83 on the disengagement subscale (Demerouti et al., 2003; Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005; Ogunsuji et al., 2022).

The more accurate McDonalds’ Omega statistic has also been reported for both subscales and the total scale, with values of .85 for disengagement, .76 for exhaustion (Reis et al., 2021) and .92 for the total scale (Sinval et al., 2019). The scale has demonstrated appropriate patterns of convergent and discriminant validity, with high correlations to the MBI subscales and lower/moderate correlations to measures of job satisfaction and depression (Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005).

Confirmatory factor analyses have supported the two-factor structure of the OLBI (exhaustion and disengagement). This structure has been validated in various cultural contexts, indicating its robustness and applicability across different occupational settings (Reis et al., 2015; Sinval et al., 2019; Subburaj et al., 2016). Partial scalar invariance was reported by Innstrand and colleagues (2016) across a variety of workers in different areas (marketing, public transport, church, IT, law, medicine, teaching). This means that most item intercepts are equivalent across groups, providing some (but not concrete) evidence that comparisons between these groups are appropriate and meaningful. Normative data is available for the OLBI across several countries and spanning various professional groups (see supplemental materials below).

For instance, Halbesleben and Demerouti (2005) reported data from working adults in the United States, while Demerouti et al. (2003) provided norms for employees in Greece. Additional studies have gathered data from psychologists in Australia (Smout, 2024), nurses in Germany (Reis et al., 2015), resident physicians in Nigeria (Ogunsuji et al., 2022), and professionals in Brazil and Portugal (Sinval et al., 2019).

Several severity classifications have been used in the literature for the total score range, involving splitting the distribution of scores into thirds (Tipa et al., 2019; Hanez & Laurant, 2018). Using ROC analysis, Leclercq and colleagues (2021) reported that scores of 44 or above are indicative of clinically significant burnout. In reviewing the literature, NovoPsych synthesised the cut points reported and created severity ranges based on the weighted total means and pooled standard deviations from studies which reported such information.

NovoPsych Total Scale Severity Categories:

NovoPsych defined the total cut off for burnout as a total raw score of 44 and higher based on the severity ranges outlined above. This decision was made by following Leclercq and colleagues (2021) and on the basis of the large sample size used to derive the weighted mean and subsequent severity ranges (n=4,463).

Below is a sample description table as well as percentile tables.

Percentile graphs below display how a score compares to the normative sample.

Each score has a corresponding percentile which indicates the percentage of people who scored the same as or lower than the given score. For example, a Total score of 48 corresponds to the 74th percentile, meaning that 74% of the normative sample have a total score of 48 or lower. These graphs help to contextualise an individuals burnout score.

*Note, on the Total score percentile graph (right) the raw score range of 8 to 23 is collapsed into a single row as these scores rounded down to zero.

Evangelia Demerouti.

Demerouti, E. (1999). Burnout: Eine Folge konkreter Arbeitsbedingungen bei Dienstleistungsund Produktionstätigkeiten [Burnout: A consequence of specific working conditions among human services, and production tasks]. Peter Lang.

Delgadillo, J., Saxon, D., & Barkham, M. (2018). Associations between therapists’ occupational burnout and their patients’ depression and anxiety treatment outcomes. Depression and anxiety, 35(9), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22766

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12–23.

https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12

Demerouti, E. (1999). Burnout: Eine Folge konkreter Arbeitsbedingungen bei Dienstleistungsund Produktionstätigkeiten [Burnout: A consequence of specific working conditions among human services, and production tasks]. Peter Lang.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Demerouti, E. (2005). The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work & Stress, 19(3), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500340728

Innstrand S. T. (2016). Occupational differences in work engagement: A longitudinal study among eight occupational groups in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(4), 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12298

Leclercq, C., Braeckman, L., Firket, P., Babic, A., & Hansez, I. (2021). Interest of a joint use of two diagnostic tools of Burnout: Comparison between the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory and the Early Detection Tool of Burnout completed by physicians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10544. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910544

Tipa, R. O., Tudose, C., & Pucarea, V. L. (2019). Measuring Burnout Among Psychiatric Residents Using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) Instrument. Journal of Medicine and Life, 12(4), 354–360. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2019-0089

Ogunsuji, O., Ogundipe, H., Adebayo, O., Oladehin, T., Oiwoh, S., Obafemi, O., Soneye, O., Agaja, O., Uyilawa, O., Efuntoye, O., Alatishe, T., Williams, A., Ilesanmi, O., & Atilola, O. (2022). Internal reliability and validity of Copenhagen Burnout Inventory and Oldenburg Burnout Inventory compared with Maslach Burnout Inventory among Nigerian resident doctors: A pilot study. Dubai Medical Journal, 5(2), 89–95.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000521376

Raju, A., Nithiya, D. R., & Tipandjan, A. (2022). Relationship between burnout, effort-reward imbalance, and insomnia among Informational Technology professionals. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 11, 296. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1809_21

Reis, C., Tecedeiro, M., Pellegrino, P., Paiva, T., & Marôco, J. P. (2021). Psychometric Properties of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory in a Portuguese Sample of Aircraft Maintenance Technicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 725099. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725099

Reis, D., Xanthopoulou, D., & Tsaousis, I. (2015). Measuring job and academic burnout with the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI): Factorial invariance across samples and countries. Burnout Research, 2(1), 8-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.11.001

Shoman, Y., Marca, S. C., Bianchi, R., Godderis, L., van der Molen, H. F., & Guseva Canu, I. (2021). Psychometric properties of burnout measures: A systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020001134

Sinval, J., Queirós, C., Pasian, S., & Marôco, J. (2019). Transcultural Adaptation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) for Brazil and Portugal. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 338. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00338

Smout, M. (2024) A pragmatic pilot study of the feasibility of a common factors supervision intervention not embedded in a training program for improving confidence, burnout, and client outcomes of psychologists in routine private practice. (Unpublished Manuscript).

Subburaj, A., & Vijayadurai, J. (2016). Translation, validation and psychometric properties of Tamil version of Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 219, 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.067

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved