The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that can be used to identify issues relating to alexithymia such as difficulty identifying and describing feelings and externally oriented thinking (Bagby et al., 1994).

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that can be used to identify issues relating to alexithymia such as difficulty recognising, describing and regulating internal emotional states (Bagby et al., 1994). The TAS distinguishes three components of alexithymia, reflected by the following subscales.

1. Difficulty Identifying Feelings

In therapy, trouble noticing emotions can hinder formulation, articulation of issues and goal setting.

2. Difficulty Describing Feelings

Clients with barriers to communication can hinder mutual understanding which may become an issue that leads to a lack of engagement in therapy.

3. Externally Oriented Thinking

High scorers may have a fixation on external stimuli as opposed to internal emotions. In addition, high scores may indicate low empathy.

The TAS is a useful tool for screening, formulation with clients, or as a predictor of therapy outcomes (Bagby et al., 1994; Kauhanen et al., 1992). As a predictor, the TAS can be particularly helpful for giving an early warning indicator of a roadblock in therapy later on. For example, people high on alexithymia are more likely to prematurely leave therapy (Sommerfeld, 2023). The TAS can help therapists identify which clients would benefit from emotional insight as a specific target for treatment. For example, increasing emotion awareness and identification in therapy can lead to improved emotion processing and selection of appropriate emotion regulation strategies to reduce distress.

Investigations have found TAS scores to be associated with psychopathology symptoms and poor well-being (Taylor et al., 1999). Using the TAS, alexithymia was found to be prevalent in depressive, anxiety, adjustment, somatoform and eating disorders (Leweke et al., 2012). Males have been observed to score significantly higher on alexithymia than females (Levant et al., 2006, 2009).

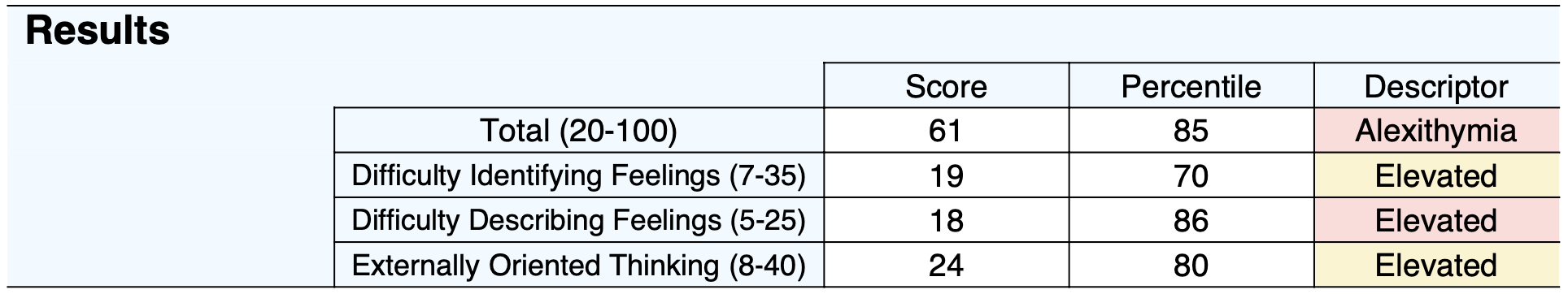

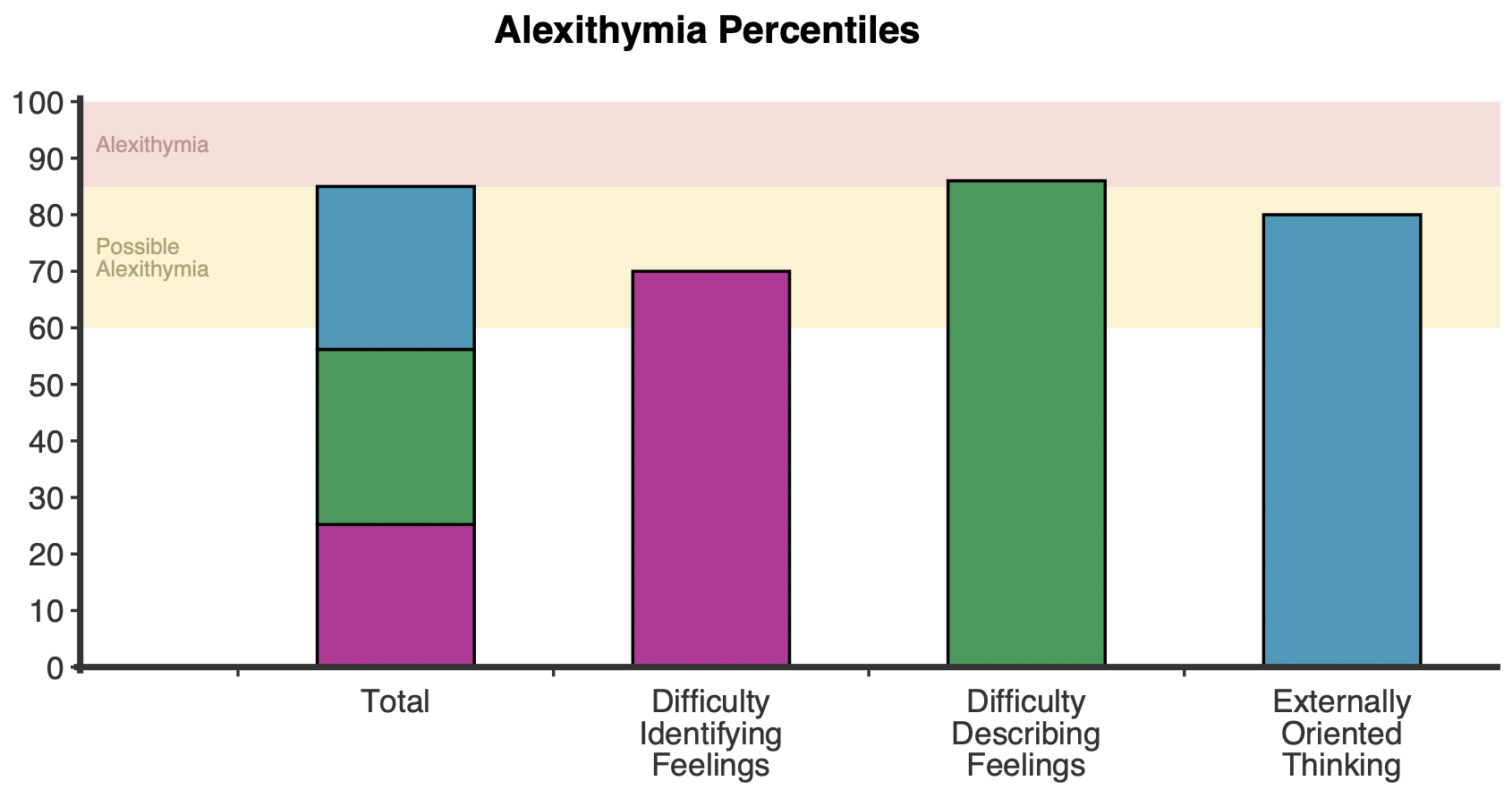

A total score from 20 to 100 is calculated by summing all 20 responses. Higher scores indicate a greater difficulty with identifying, describing and processing emotions.

Ranges for clinical significance (Bagby & Taylor, 1997) are as follows.

When interpreting TAS total scores in the context of case conceptualisation, clinicians may wish to consider that the TAS does not distinguish between the different ways of classifying and understanding alexithymia evident in the literature. Alexithymia can be thought of as primary (developmental) or secondary (the result of psychological stress, illness or disease arising after childhood) in nature (Messina et al., 2014). This classification system shares similarities to the conceptualisation of alexithymia as a trait (relatively stable personality characteristic) or state (temporary or situational) phenomena (de Bruin et al., 2019). This classification concept can have treatment implications within some therapeutic frameworks as, for example, secondary or state alexithymia may be formulated as a defence mechanism protecting against emotional introspection. The development of a consensus remains the subject of ongoing research.

Difficulty Identifying Feelings: Items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 13, and 14

– The ability to recognise and identify internal emotions and distinguish between different feelings and bodily sensations. In therapy, trouble noticing emotions can hinder formulation, articulation of issues and goal setting.

Difficulty Describing Feelings: Items 2, 4, 11, 12, and 17

– The comfort and accuracy with which individuals can express their emotions to others. Includes the ability to find words for emotions and share those feelings effectively. Barriers to communication can hinder mutual understanding which may become an issue that leads to a lack of engagement in therapy.

Externally Oriented Thinking: Items 5, 8, 10, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 20

– The extent to which individuals tend to focus their attention on external events rather than internal experiences. High scorers may have a fixation on external stimuli as opposed to internal emotions. In addition, high scores may indicate low empathy.

The TAS was developed by Bagby and colleagues (1994) and was based on initial 26-item and revised versions (Taylor et al., 1985, 1992). Hundreds of investigations have been carried out on the TAS that have examined various aspects of its psychometric properties (Sekely et al., 2018). In these works, appropriate patterns of convergent and discriminant validity have been observed, and a large majority are consistent on a three-factor solution (Bagby et al., 2020). Subscale scores can be calculated however the most reliable estimate of alexithymia comes from the total score (Parker et al., 2008). The scale has been validated in clinical and non-clinical samples (Bagby et al., 2020).

Cronbach’s alpha values have been reported in support of the internal reliability of the TAS-20. In a global psychometric review including data from 22 countries, Taylor and colleagues (2003) observed alpha values of above .70 for all countries except Poland.

Furthermore, normative data is available for a clinical sample of psychiatric outpatients with various presentations (N = 218, Mean = 63.84, SD = 13.06). A normative sample provides data on typical patterns of responding in a community population (Bagby, 1994), indicating that men (Mean = 51.14, SD = 10.4) score significantly higher than women (Mean = 48.99, SD = 11.48). Preece and colleagues (2020) found similar patterns of responding in a normative community sample.

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale–I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (2020). Twenty-five years with the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 131, 109940. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109940

Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale–I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

de Bruin, P. M. J., de Haan, H. A., & Kok, T. (2019). The prediction of alexithymia as a state or trait characteristic in patients with substance use disorders and PTSD. Psychiatry research, 282, 112634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112634

Kauhanen, J., Julkunen, J., & Salonen, J. T. (1992). Validity and reliability of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) in a population study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 36(7), 687-694.

Levant, R. F., Hall, R. J., Williams, C. M., & Hasan, N. T. (2009). Gender differences in alexithymia. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 10(3), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015652

Levant, R. F., Good, G. E., Cook, S., O’Neil, J., Smalley, K. B., Owen, K. A., & Richmond, K. (2006). Validation of the Normative Male Alexithymia Scale: Measurement of a gender-linked syndrome. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 7, 212–224.

Leweke, F., Leichsenring, F., Kruse, J., & Hermes, S. (2012). Is alexithymia associated with specific mental disorders. Psychopathology, 45, 22–28.

Loas, G., Braun, S., Delhaye, M., & Linkowski, P. (2017). The measurement of alexithymia in children and adolescents: Psychometric properties of the Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children and the twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale in different non-clinical and clinical samples of children and adolescents. PloS one, 12(5), e0177982. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177982

Messina, A., Beadle, J.N., & Paradiso, S. (2014). Towards a classification of alexithymia: Primary, secondary and organic. Official Journal of the Italian Society of Psychopathology, 20, 38-49.

Preece, D. A., Petrova, K., Mehta, A., Sikka, P., & Gross, J. J. (2024). Alexithymia or general psychological distress? Discriminant validity of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale and the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire. Journal of Affective Disorders, 352, 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.271

Sekely, A., Bagby, R. M., & Porcelli, P. (2018). Assessment of the alexithymia construct. In O. Luminet, R. M. Bagby, & G. J. Taylor (Eds.), Alexithymia: Advances in research, theory, and clinical practice (pp. 17–32). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108241595.004

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. A. (1997). Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511526831

Taylor, G. J., Ryan, D., & Bagby, R. M. (1985). Toward the development of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 44(4), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1159/000287912

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (1992). The Revised Toronto Alexithymia Scale: some reliability, validity, and normative data. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 57(1-2), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288571

Taylor, G.J., Bagby, R.M., and Parker, J.D.A. (2003). The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale – IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 277–283.

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved