The Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire–3 (RBQ-3) is a 20-item scale designed to measure restricted and repetitive behaviours, a core feature of Autism (Jones et al. 2024).

The RBQ-3 can be used with persons aged 13 and above without co‐occurring intellectual disability. The scale is designed to measure restricted and repetitive behaviours, a core feature of Autism found in the DSM-5 criteria (Jones et al. 2024). The DSM-5 informed the scale’s creation in addition to other sources such as the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO) (Wing et al., 2002). Restricted and repetitive behaviours may best be characterised as structured, specialised interests and repeated self-expressive sensory-motor behaviours (APA, 2013; Leekam et al, 2011).

The distinction between structured, specialised interests and repeated self-expressive sensory-motor behaviours aligns with the DSM-5 framework and is well-supported by research (Tian et al., 2022).

The RBQ-3 contains two primary subscales:

RBQ-3 scores can provide valuable insights into specialised interests and self-expressive sensory-motor behaviours that can make up part of a more comprehensive assessment for Autism. Jones et al. (2024) demonstrated that RBQ-3 scores distinguish Autistic individuals from neurotypical individuals, supporting its use in assisting with preliminary evaluation.

For Autistic Individuals, the RBQ-3 offers assistance to clinicians in identifying whether a client’s needs or challenges may be related more to self-expressive sensory-motor behaviours or to specialised interests. Distinctions are relevant when informing a therapeutic approach, for example, a high IS subscale score might indicate the need for support around significant life transitions and managing anxiety related to change, while a high RSMB subscale score might suggest addressing sensory challenges or needs.

The RBQ-3 self-report version can help address discrepancies between an individual’s assessment of their behaviours and an observer’s. For example, an Autistic person might mask or internalise certain repeated behaviours in public, leading informants (like parents or clinicians) to under-report them.

When interpreting RBQ-3 scores, it is important to determine whether repeated behaviours are primarily autism-related, or whether they could be explained by similar phenomena other than, or co-occurring with Autism, such as ADHD, OCD, Fragile X, Tourettes and anxiety disorders (Moss et al., 2008). These behaviours can serve many different functions. For example, some people may be seeking sensory stimulation, regulating stress or anxiety, coping with an overstimulating environment, alleviating boredom, or simply enjoying the motion itself. In Autism, such behaviours are linked primarily to sensory or reward mechanisms but may also be influenced by anxiety or stress. By contrast, in conditions such as OCD, repetitive behaviours are primarily driven by anxiety relief and in the case of ADHD are driven by self-regulation and symptom management i.e., outlet for hyperactivity/impulsivity. Clinicians should also consider whether such behaviours are adaptive (e.g., soothing and harmless) or disruptive and potentially harmful. High RBQ-3 scores without significant anxiety-driven motivations or disruptions to functioning suggest an autism-related origin.

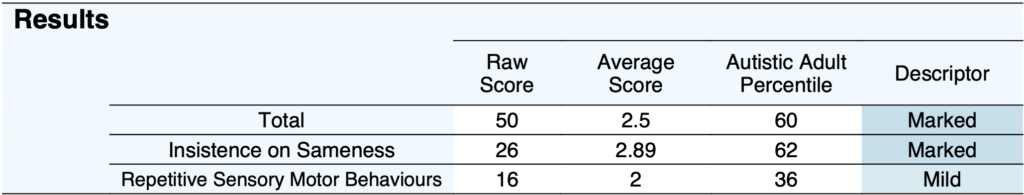

Scores are typically reported in the literature as averages across all items or by subscale (range 1-4). These can also be understood as raw scores, with the total raw score ranging from 20-79 for example. Higher total scores indicate a greater presence of structured, specialised interests and repeated sensory-motor behaviours.

Subscale raw score ranges differ and are listed below:

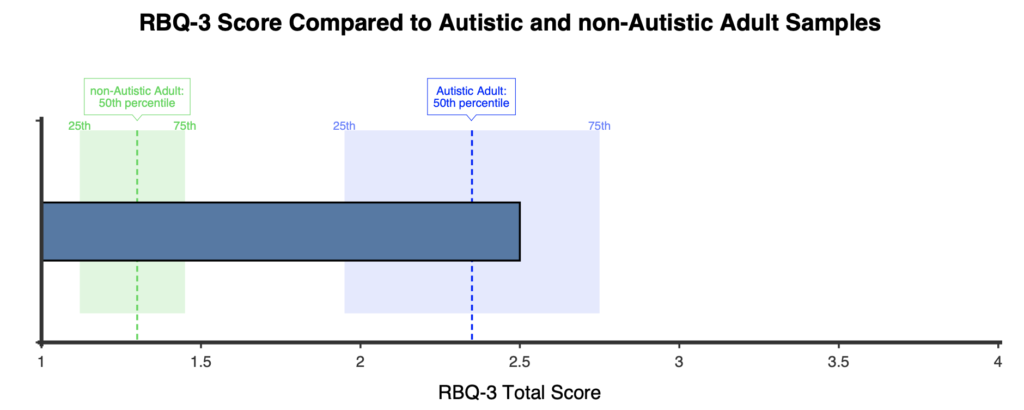

Percentiles are presented that are based upon a sample of Autistic adults (n = 110) for the total and subscale scores. Percentiles give context to a client’s score, showing how they compare to others, for example, a percentile of 50 represents the typical level of specialised interests and repeated sensory-motor behaviours among Autistic adults.

Category guidelines were created by NovoPsych to assist in interpreting scores, and were based on response options, average scores and the percentile distribution of the total score in the Autistic adult sample:

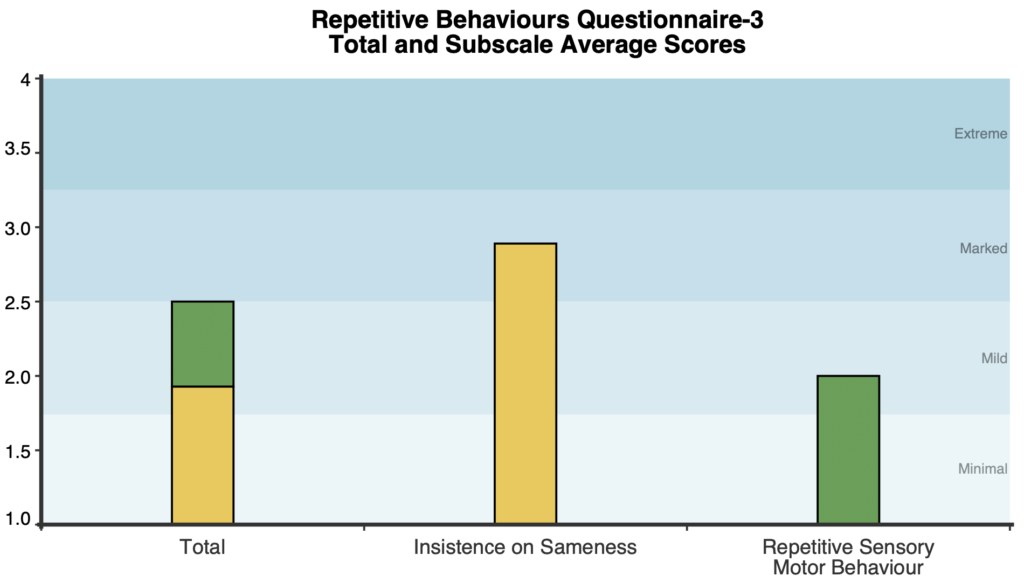

On the first administration, a stacked bar graph shows the total, IS and RSMB results in average scores (1-4).

A horizontal comparison graph is also presented showing the respondent’s score in comparison to Autistic and non-Autistic adult samples.

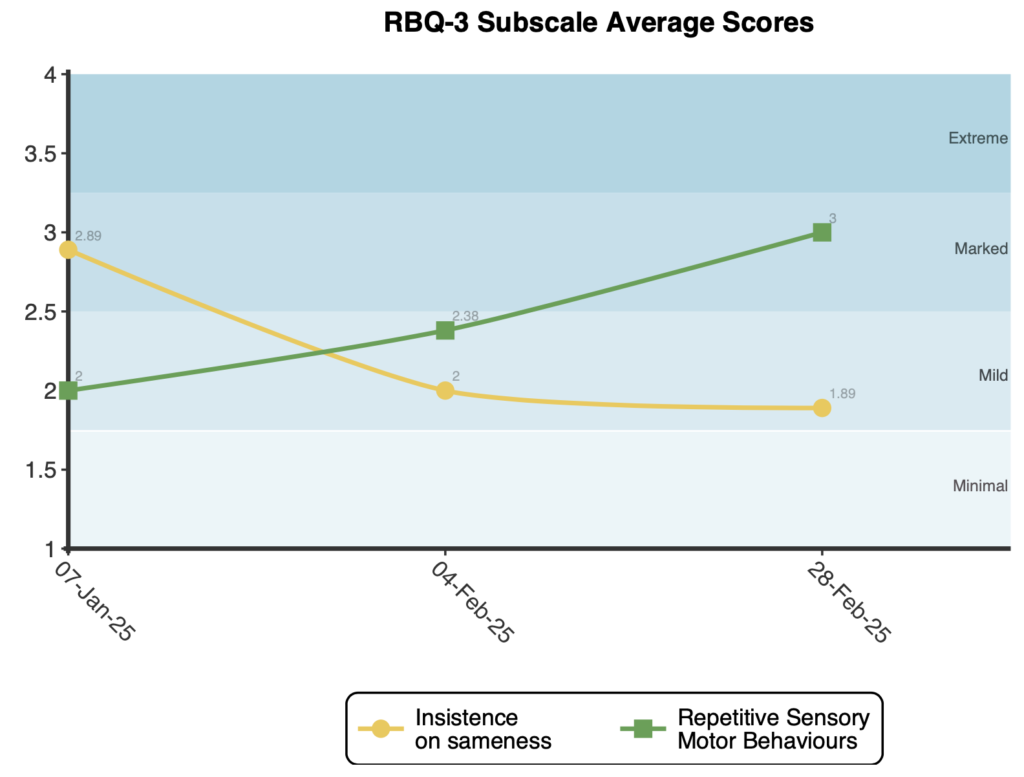

When administered more than once, a line graph is presented for the subscale average scores over time.

In addition, a new stacked bar graph and comparison horizontal bar graph are included reflecting the current scores.

Jones et al. (2024) examined the RBQ-3 alongside the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders-Abbreviated (DISCO-Abbreviated). They observed moderate correlations (r= .45–.54) between RBQ-3 total scores and the DISCO-Abbreviated restricted and repetitive behavior domain, indicating good convergent validity. Furthermore, Jones et al. (2024) compared Autistic and non-Autistic adults, finding the Autistic group scored significantly higher on RBQ-3 total scores and on the two subscales (RSMB, IS) compared to the non-Autistic group, with large effect sizes. This is in line with earlier findings from the previous version, the RBQ-2A (Barrett et al., 2015).

The RBQ-3 is yet to be investigated for dimensionality and is assumed to retain the established two-factor structure of repeated motor-sensory behaviours and insistence on sameness that earlier analyses on the RBQ-2A had demonstrated in both children and adults (Barrett et al., 2015; Honey et al., 2012).

Jones et al. (2024) reported good to excellent internal consistency for total scores (α=.89, .82) in Autistic and non-Autistic adults. The RSMB and IS subscales also showed acceptable-to-good alpha values (α=.68–.85). McDonald’s ω coefficients were comparable, indicating that items on each subscale measure coherent underlying constructs.

Normative data is provided for the initial sample of n=110 Autistic adults without intellectual disability. Observed average scores (1-4) and standard deviations are reported for the total M=2.48(.61), RSMB subscale M=2.25(.68), IS subscale M=2.68(.69). Converted from average scores to raw scores based on their respective ranges these are: total (range 20-79) M=47.12(11.59), RSMB subscale (range 8-32) M=18.0(5.54), IS subscale (range 9-36) M=24.12(6.21). Additionally, data from a sample of non-Autistic adults is available, with raw score means for the total M=25.65(4.75), and subscales RSMB M=10.32(2.64), IS M=12.24(2.7). Further normative data is reported for n=151 self-reported Autistic adults and n=151 self-reported non-Autistic adults sampled online (Jones et al., 2024).

Category guidelines were created by NovoPsych based on the RBQ-3 response options to assist in interpreting scores. These ranges are outlined below:

-Average score 1.0-1.74 | Minimal | Behaviours are rare or absent

-Average score 1.75-2.49 | Mild | Occasional or mild behaviours

-Average score 2.5-3.24 | Marked | Noticeable and more frequent behaviours

-Average score 3.25-4.0 | Extreme | Frequent and intense behaviours

Clinicians can use the available normative data on Autistic adults for comparison. If using the RBQ-3 with a child or adolescent, one might cautiously compare their score to the adult Autistic benchmark.

Jones, C. R. G., Livingston, L. A., Fretwell, C., Uljarević, M., Carrington, S. J., Shah, P., & Leekam, S. R. (2024). Measuring self and informant perspectives of restricted and repetitive behaviours (RRBs): Psychometric evaluation of the Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire-3 (RBQ-3) in adult clinical practice and research settings. Molecular Autism, 15(1), Article 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-024-00603-7

Bartholomew, E., Hegarty, D. Smyth, C., Buchanan, B., Baker, S. (2025). Bartholomew, E., Smyth, C., Buchanan, B., Baker, S., Hegarty, D. (2025). A Review of the Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire-3 (RBQ-3): Qualitative Descriptors, Psychometric Properties, and Normative Data.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Barrett, S. L., Uljarević, M., Jones, C. R. G., & Leekam, S. R. (2015). Assessing subtypes of restricted and repetitive behaviour using the Adult Repetitive Behaviour Questionnaire-2 in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 6, Article 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0023-6

Honey, E., McConachie, H., Turner, M., & Rodgers, J. (2012). Validation of the repetitive behaviour questionnaire for use with children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.009

Jones, C. R. G., Livingston, L. A., Fretwell, C., Uljarević, M., Carrington, S. J., Shah, P., & Leekam, S. R. (2024). Measuring self and informant perspectives of restricted and repetitive behaviours (RRBs): Psychometric evaluation of the Repetitive Behaviours Questionnaire-3 (RBQ-3) in adult clinical practice and research settings. Molecular Autism, 15(1), Article 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-024-00603-7

Jiujias, M., Kelley, E., & Hall, L. (2017). Restricted, repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparative review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(6), 944–959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-017-0717-0

Leekam, S. R., Prior, M. R., & Uljarević, M. (2011). Restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders: A review of research in the last decade. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 562–593. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023341

Tian, J., Gao, X., & Yang, L. (2022). Repetitive restricted behaviors in autism spectrum disorder: From mechanism to development of therapeutics. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 780407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.780407

Wing, L., & Gould, J. (2002). The Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders: Background, inter-rater reliability and clinical use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00023

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved