The Anxiety, Depression, and Mood Scale (ADAMS) is an informant-report screening tool used to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders in individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) (Esbensen et al., 2003).

The scale can be utilised to screen and monitor long-term outcomes in individuals with ID aged 10 years and older. Individuals who have maintained regular interaction with a person with ID for more than six months, including caretakers, professionals, employment supervisors, relatives, teachers, or other involved parties, can use the ADAMS.

The ADAMS consists of 28 items organised into five subscales:

The ADAMS offers a valuable tool for assessing emotional and behavioural issues in individuals with ID via an informant. It provides an assessment framework for early detection that focuses on mood challenges common in those with ID, however often overlooked. Using ADAMS, clinicians can identify symptoms proactively, even in situations where individuals may face challenges with communication or cognitive processing.

Individuals with ID who experience high levels of anxiety, mood disturbances, and depression may encounter difficulties in sustaining a high quality of life compared to those with fewer symptoms (Horovitz et al., 2014). Notably, recent studies highlight the efficacy of therapeutic interventions in reducing depressive symptoms among individuals with ID (Hamers et al., 2018). These interventions consistently demonstrate potential for enhancing mental well-being, providing a hopeful route to better overall mental health and quality of life for individuals with ID.

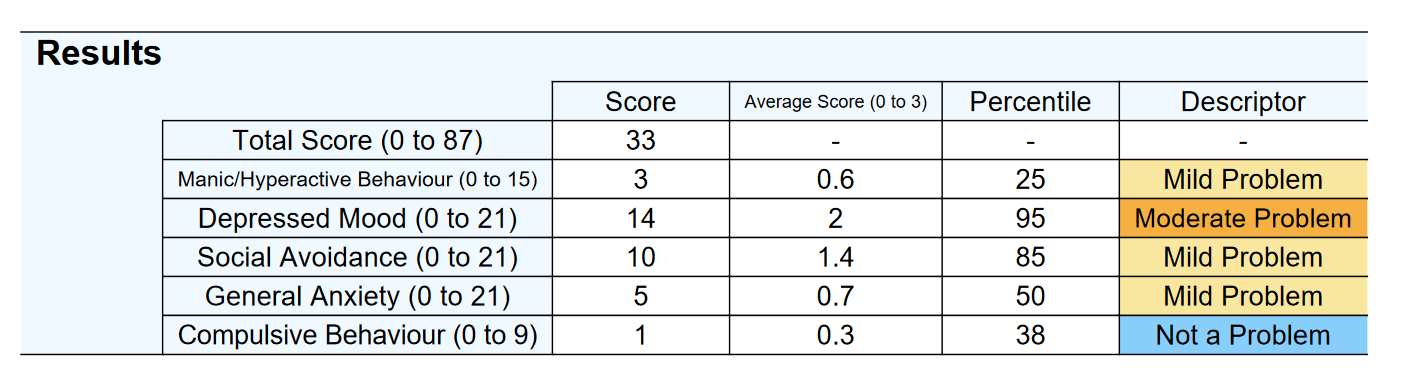

Emphasis is placed upon the subscale scores, with higher scores being indicative of more severe symptomatology.

Note. Item 3 appears in both the Manic/Hyperactive Behaviour and General Anxiety subscales.

A percentile is used to illustrate how a respondent’s score compares to normative responses from intellectually disabled individuals in the reference sample by Esbensen et al. (2003). A percentile of 50 suggests typical responding patterns compared to people with ID. Conversely, a percentile of 99 indicates that the respondent scores higher than 99 per cent of individuals, indicating severe symptoms.

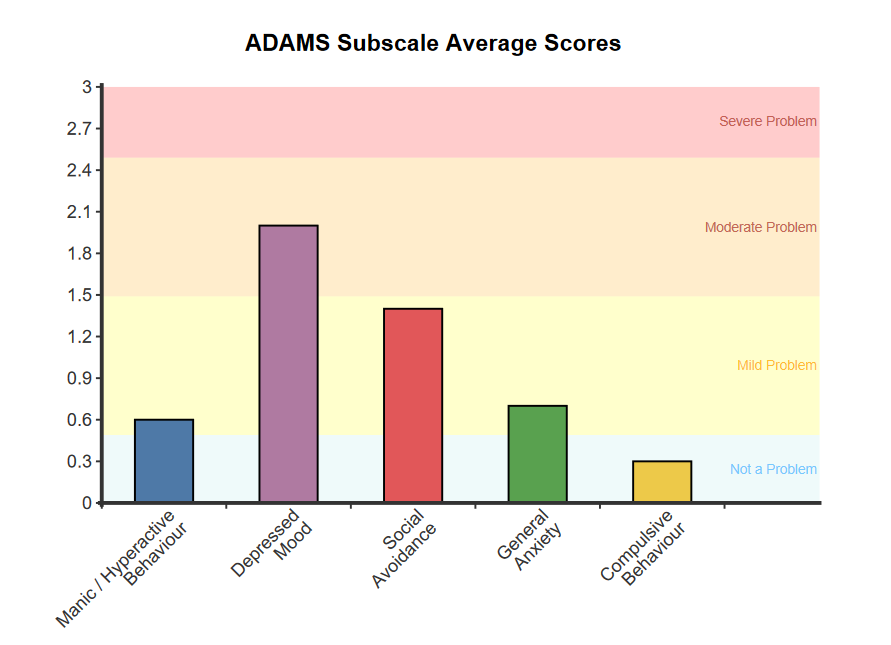

The ADAMS subscale average scores are categorised using the following qualitative descriptors:

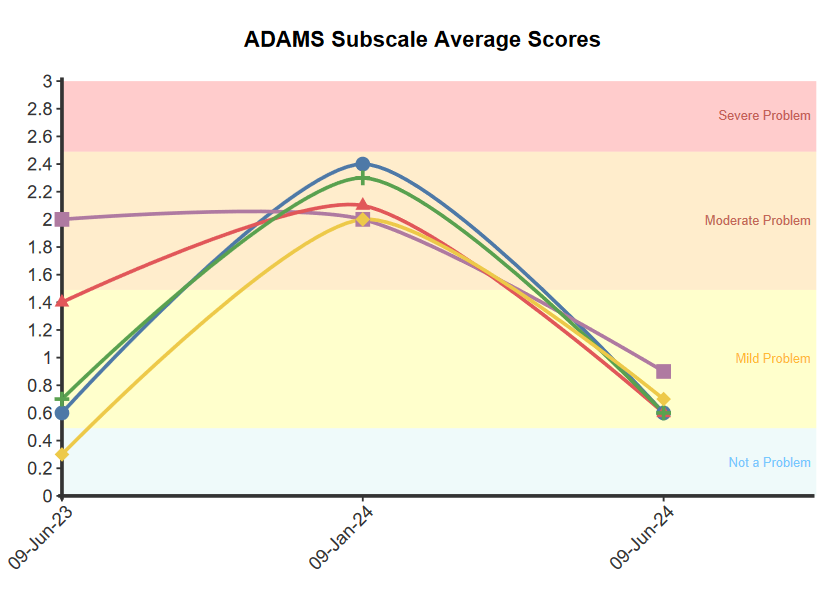

For multiple administrations, the line graph visually tracks the respondent’s results across sessions. A meaningful change (~ 0.5 SD) in the score is defined as an increase or decrease of 2 or more points for Manic/Hyperactive Behaviour, Depressed Mood, Social Avoidance, and General Anxiety subscales, and at least 1 point for the Compulsive Behaviour subscale. This criterion is based on the Minimally Important Difference (MID) calculation specific to each subscale. Such changes indicate meaningful improvement or reduction in symptoms, while a change of less than the specified points suggests no meaningful change in symptom severity between assessments.

Intellectually disabled individuals with elevated levels of anxiety, mood disturbances, and depression may face additional challenges in maintaining a high quality of life compared to those with lower levels of symptomatology (Horovitz et al., 2014). Importantly, recent research underscores the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in alleviating depressive symptoms among individuals with ID (Hamers et al., 2018). Such interventions consistently show promise in enhancing mental well-being in this population, offering a positive pathway to improve overall mental health and quality of life.

The items of the ADAMS are derived from DSM criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2005), clinical expertise, and other assessment tools (e.g. the Prout-Strohmer Assessment System, the Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped-II, Psychopathology Instrument for Mentally Retarded Adults, and Self-Report Depression Questionnaire) (Esbensen et al., 2003).

The five-factor structure was determined through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using a sample of 265 informants (51.9% male) responding on behalf of individuals with ID. The age range of the participants was 10 to 79 years, with a mean age of 39.2 years and a standard deviation of 11.3 years. Items with factor loadings greater than 0.40 were retained, resulting in the final 28-item scale (Esbensen et al., 2003).

The following are the means and standard deviations for each ADAMS subscale (Esbensen et al., 2003):

The test-retest reliability for the total ADAMS scale has been reported to be excellent (ICC= 0.81) (Esbensen et al., 2003). For the individual subscales, the test-retest reliability over 30 days was:

The ADAMS subscales demonstrate good convergent validity through strong positive correlations with related constructs from other measures. The Depressed Mood subscale demonstrates a positive correlation with the self-report Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-SR; r = 0.44), and with the informant-report Signalising Depression List for people with Intellectual Disabilities (SDL-ID; r = 0.71). Similarly, the General Anxiety subscale exhibits positive correlations with both the Glasgow Anxiety Scale for people with an intellectual disability (GAS-ID; r = 0.37) and the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A; r = 0.41) (Hermans et al., 2012). The ADAMS Manic/Hyperactive subscale correlates significantly with the Assessment of Dual Diagnosis (ADD) Mania subscale (r = 0.55). Discriminant validity is supported by weak or non-existent correlations between ADAMS subscales and conceptually unrelated subscales like the ADD Sexual Disorders subscale and the Social Skills and Communication Skills subscales (Rojahn et al., 2011).

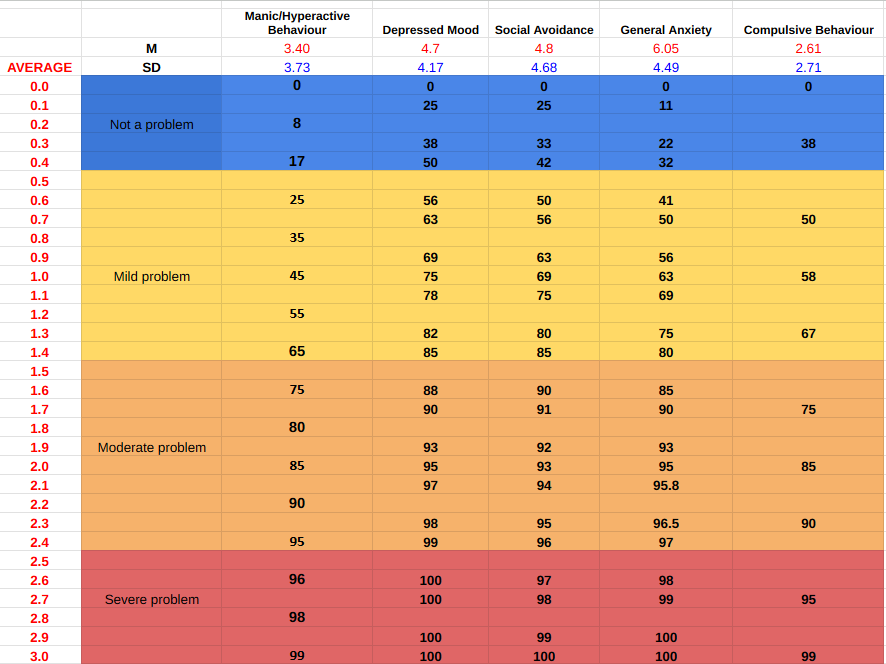

Percentiles and severity descriptors are presented for each subscale of the ADAMS. NovoPsych determined that each qualitative descriptor corresponds to a specific range of average scores for a given subscale. The ranges for these descriptors were determined using two normative samples: one consisting of 265 informants (51.9% male; Mage = 39.2, SD = 11.3, age range 10-79) and one consisting of 268 informants (53.2% male; Mage = 39, SD = 13, age range 10-79) representing individuals with ID.

The ADAMS subscale average scores are categorised using the following qualitative descriptors:

The percentile table below illustrates how an average score compares to the normative sample of individuals with ID (Esbensen et al., 2003). Each possible average score is accompanied by a corresponding percentile, indicating the percentage of individuals who scored the same or lower. For instance, an average score of 1.4 corresponds to the 65th percentile of the Manic/Hyperactive subscale in the normative sample, signifying that 65% of the sample had an average score of 1.4 or lower. These graphs are instrumental in contextualising an individual’s average scores on each subscale, providing a clearer understanding of their standing relative to other individuals with ID.

Esbensen, A. J., Rojahn, J., Aman, M. G., & Ruedrich, S. (2003). Reliability and validity of an assessment instrument for anxiety, depression, and mood among individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000005999.27178.55

American Psychiatric Association (2005). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition (Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Esbensen, A. J., Rojahn, J., Aman, M. G., & Ruedrich, S. (2003). Reliability and validity of an assessment instrument for anxiety, depression, and mood among individuals with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(6), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000005999.27178.55

Hermans, H., Jelluma, N., van der Pas, F. H., & Evenhuis, H. M. (2012). Feasibility, reliability and validity of the Dutch translation of the Anxiety, Depression And Mood Scale in older adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(2), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.018

Horovitz, M., Shear, S., Mancini, L. M., & Pellerito, V. M. (2014). The relationship between Axis I psychopathology and quality of life in adults with mild to moderate intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(1), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.014

Hamers, P. C. M., Festen, D. A. M., & Hermans, H. (2018). Non‐pharmacological interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities and depression: a systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(8), 684–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12502

Rojahn, J., Rowe, E. W., Kasdan, S., Moore, L., & van Ingen, D. J. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist, the Anxiety, Depression and Mood Scale, the Assessment of Dual Diagnosis and the Social Performance Survey Schedule in adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2309–2320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.035

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved