The Compassion Motivation and Action Scale (CMAS) is an 18-item self-report measure designed to assess compassion for oneself. There are two CMAS scales measuring two dimensions of compassion, self-compassion (CMAS-self) and compassion to other people (CMAS-other: Steindl et al., 2021).

The CMAS-self has three subscales:

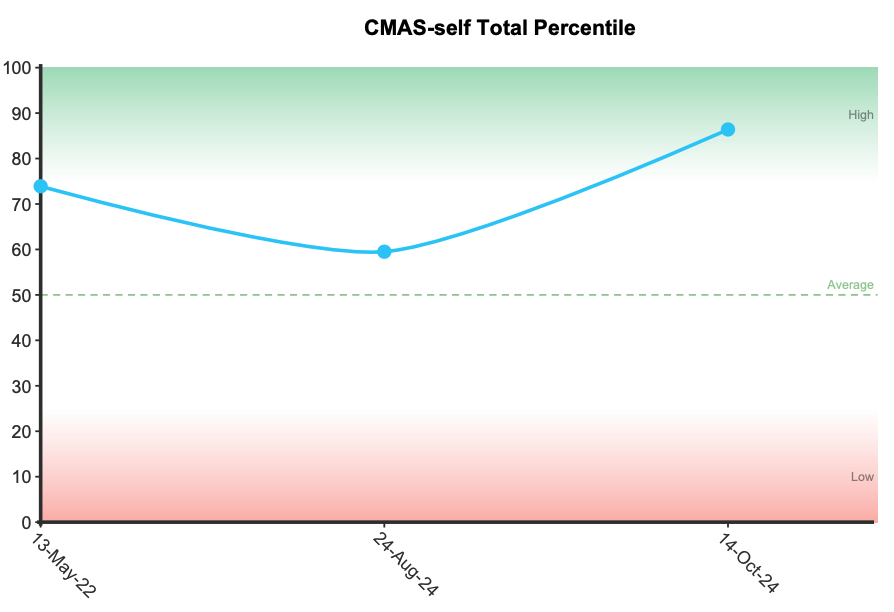

The CMAS-self was designed to be specifically used as a measure of the change in compassionate motivation and action over time in clinical practice and intervention research.

It can be important to measure self-compassion given that the development of compassionate motivation has been found to be associated with benefits physiologically (Kim et al., 2020; Klimecki et al., 2014; Matos et al., 2017), psychologically (Kirby, 2016; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012), and relationally (Crocker & Canevello, 2012; Kirby & Laczko, 2017; Seppala et al., 2012).

It has been found that compassion-based interventions are effective at increasing self-reported compassion, self-compassion and mindfulness, reducing depression, anxiety and psychological distress symptoms, and improving well-being (Kirby et al., 2017).

All items are summed to provide an overall score, with higher scores indicative of more self-compassion. Subscale scores are also provided to enable a comparison between subscales:

Self-Compassion Intention (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) – the intent to and value one places on being supportive, accepting and compassionate towards oneself.

Self-Compassion Distress Tolerance (items 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12) – the ability to and confidence in tolerating distress by oneself when experiencing suffering.

Self-Compassionate Action (items 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18) – the frequency of self-compassionate actions and behaviours over the past week compared to normal.

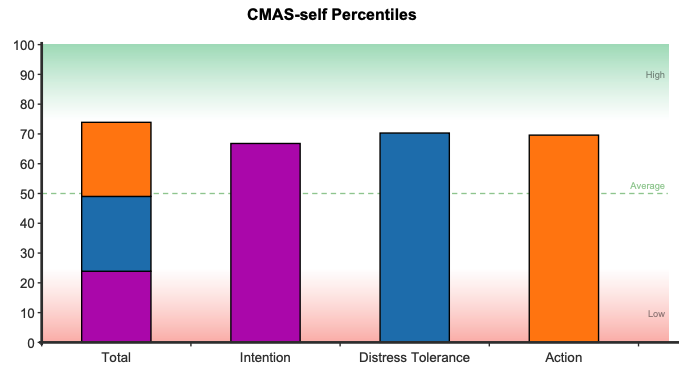

A normative percentile for the total score and subscales are calculated based on a sample from Australia, USA, UK, and New Zealand (Steindl et al., 2021), indicating how the respondent scored in relation to a typical pattern of responding for adults. For example, a percentile of 50 indicates typical (and healthy) patterns of self-compassion, whereas a percentile of 5 indicates very low levels of self-compassion.

Results are presented in a graph, which indicates the percentile for total self-compassion and sub-scales compared to a normative sample, with a dotted line at 50 indicating average self-compassion..

The CMAS-self was developed using an initial item pool that was generated on the basis of a review of existing measures in combination with the dimensions of motivational language in motivational interviewing. The initial item pool was disseminated to six international experts who were researchers and clinicians each with over 20 years experience in the compassion and/or motivational interviewing literature for feedback and to ensure that wording and content were culturally relevant. Following the development and consultation process, the initial pool of items was evaluated via exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to reduce the items further.

There was very good internal consistency present for the CMAS-self with an overall Chronbach’s alpha of 0.94 and subscale consistencies of 0.92 (Intention), 0.95 (Distress tolerance), and 0.94 (Action).

For 621 adults from Australia, USA, UK, and New Zealand, the mean score was 90.79 (SD = 17.52) for the CMAS-self, 30.95 (SD = 4.72) for the Intention subscale, 34.13 (SD = 9.14) for the Distress Tolerance subscale, and 25.70 (SD = 8.38) for the Action subscale (Steindl et al., 2021).

Steindl, S. R., Tellegen, C. L., Filus, A., Seppälä, E., Doty, J. R., & Kirby, J. N. (2021). The Compassion Motivation and Action Scales: a self-report measure of compassionate and self-compassionate behaviours. Australian Psychologist, 56(2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1893110

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2012). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575.

Kim, C., et al. (2020). Exploring the psychophysiological effects of compassion-focused therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2364.

Kirby, J. N., & Laczko, D. (2017). The role of mindfulness in compassion-based interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 46–59.

Kirby, J. N. (2016). The clinical psychology of compassion. Clinical Psychologist, 20(3), 105–116.

Klimecki, O., et al. (2014). The neuroscience of compassion. Psychological Science, 25(3), 376–385.

Macbeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring the association between compassion and psychological well-being. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552.

Matos, M., et al. (2017). Effects of compassion cultivation training on psychological and physiological well-being. Mindfulness, 8(4), 960–969.

Seppala, E. M., et al. (2012). Loving-kindness meditation: A tool to increase compassion for others. Psychological Science, 24(1), 48–55.

NovoPsych’s mission is to help mental health services use psychometric science to improve client outcomes.

© 2023 Copyright – NovoPsych – All rights reserved